Roberta Mameli Soprano

Bernhard Forck Concertmaster and Musical Director

Members of the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin

Students of the Barenboim-Said Akademie

Roberta Mameli Soprano

Bernhard Forck Concertmaster and Musical Director

Elfa Rún Kristinsdóttir, Ramez Atia*, Maria Arteeva*, Mohammadreza Bahrami*,

Yalda Farsani*, Paula Mejía España*, Yume Zamponi* Violin

Clemens Nuszbaumer, Çise Ataş*, Mathilde Weil* Viola

Katharina Litschig, Parya Moulaei*, Ayoub Rabah* Cello

Juliane Bruckmann, Omar Bishara* Double Bass

Nehir Göndermez*, Doğa Temelli* Oboe

Hüma Beyza Ünal* Bassoon

Thor-Harald Johnsen Lute

Raphael Alpermann Harpsichord

*Students of the Barenboim-Said Akademie

Program

Arias and Instrumental Works by

Francesco Maria Veracini

Johann Adolf Hasse

Unico Wilhelm van Wassenaer

Leonardo Vinci

Antonio Vivaldi

George Frideric Handel

Alessandro Scarlatti

Francesco Maria Veracini (1690–1768)

Overture No. 6 in G minor

Johann Adolf Hasse (1699–1783)

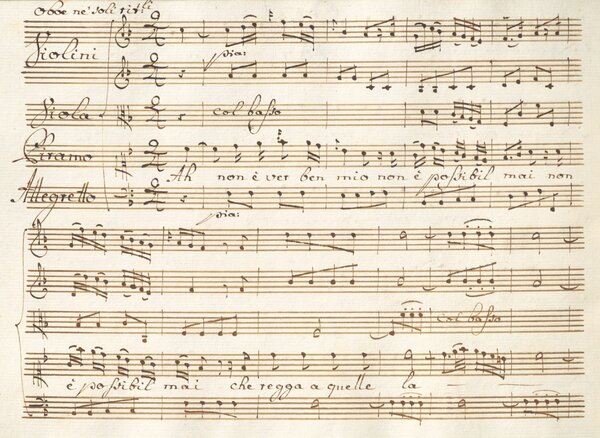

“Ah! non è ver, ben mio”

Pyramus’s aria from Piramo e Tisbe (1768/70)

Unico Wilhelm van Wassenaer (1692–1766)

Concerto armonico No. 5 in F minor (1725–40)

I. Adagio – Largo

II. Da capella

III. A tempo comodo

IV. A tempo giusto

Leonardo Vinci (1690–1730)

“Gelido in ogni vena”

Cosroe’s aria from Siroe, re di Persia (1726)

Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741)

“Ah, fuggi rapido”

Astolfo’s aria from Orlando furioso RV 819 (1714)

Intermission

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

Overture to Ariodante HWV 33 (1735)

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725)

Concerto No. 2 in C minor

from Six Concertos in Seven Parts

I. Larghetto

II. Tempo giusto

III. Andante

IV. Allegro

George Frideric Handel

“Guardian Angels”

Beauty’s aria from The Triumph of Time and Truth HWV 71 (1757)

Concerto grosso in G major Op. 6 No. 1 HWV 319 (1739–40)

I. A tempo giusto

II. Allegro

III. Adagio

IV. Allegro

V. Allegro

“Dopo notte, atra e funesta”

Ariodante’s aria from Ariodante

George Frideric Handel, anonymous portrait (before 1750)

An Eighteenth-Century Network

Europe in the early 18th century was a powerful engine of cultural ferment and innovation, and a constant flow of two-way migration—especially between Italy and the German-speaking lands north of the Alps—fostered the development of a genuinely international style. All seven composers featured on tonight’s program played a part in this epochal transition, but none exerted a greater or more widespread influence than George Frideric Handel.

Program Note by Harry Haskell

An Eighteenth-Century Network

Music of the European Baroque

Harry Haskell

Europe in the early 18th century, much like today, was a powerful engine of cultural ferment and innovation fueled by competing traditions, dogmas, and nationalisms. A constant flow of two-way migration—especially between Italy, which Heinrich Schütz a century earlier called “the true university of music,” and the German-speaking lands north of the Alps—supported far-flung networks of musicians and patrons, and fostered the development of a genuinely international style. The porous boundaries between vocal and instrumental music in this era were reflected in the increasing popularity of opera and the instrumental concerto, as the clearly delineated harmonies, melodies, and rhythms of the Baroque gradually gave way to the more nuanced expressive language and expansive formal structures of the Classical era. All seven composers featured on tonight’s program played a part in this epochal transition, but none exerted a greater or more widespread influence than George Frideric Handel.

The Composers

Handel epitomized the cosmopolitanism of the Baroque period. Born in Halle (and baptized Georg Friedrich Händel), he cut his musical teeth in Hamburg in the first decade of the 18th century. After playing violin and harpsichord in the opera orchestra for several years, he headed to Italy for finishing school. The Venetian production of Agrippina in the winter of 1709–10 gave him his first taste of success as an opera composer. From Italy he proceeded to London, where he scored another hit with Rinaldo, thanks in part to its crowd-pleasing waterfalls, fireworks, and other scenic effects. Although Handel soon branched out into other fashionable genres—anthems, odes, cantatas, keyboard music, serenades, and music for royal occasions—the stage remained central to his career for more than three decades; it was largely thanks to him that Georgian London became one of Europe’s operatic capitals. By the time Handel took out British citizenship in 1727, the English had claimed him as their foremost living composer. Starting in the late 1730s, he displayed his genius for vivid characterization and musical scene painting in sacred oratorios like Saul, Messiah, and Judas Maccabeus, which were essentially operas for the concert hall.

Of the other six composers on our program, all but one were closely identified with the lyric stage as well. One of the foremost violinists of his day, Francesco Maria Veracini rose to prominence in his native Italy and spent extended periods in Germany and England, where he vied with Handel for the affection of British opera lovers. By contrast, his compatriot and fellow virtuoso Antonio Vivaldi was based in Venice for most of his life. Although he is best known for his brilliantly inventive instrumental concertos, Vivaldi also composed several dozen operas (94 by his tally, of which only 22 have come down to us) on mythological and historical themes, as well as numerous sacred vocal works. Like Vivaldi, German composer Johann Adolf Hasse taught at one of Venice’s famed ospedali (charitable hospices that doubled as conservatories); his relationship with his fiery-tempered Italian colleague was contentious, particularly in the field of opera. Hasse’s wife, the superstar soprano Faustina Bordoni, created roles in several of Handel’s operas. Although Alessandro Scarlatti and Leonardo Vinci were born a generation apart, both wrote dozens of operas that graced stages up and down the Italian peninsula; Hasse studied under Scarlatti in Naples and considered him Italy’s greatest “master of harmony.” The odd man out in this operatic fraternity is Count Unico Wilhelm von Wassenaer, a Dutch diplomat who is remembered today chiefly for the half-dozen Concerti armonici (Harmonic Concertos) that he published anonymously in London in 1740. Once thought to be the work of Handel, they were long erroneously attributed to Giovanni Battista Pergolesi.

The Music

Veracini’s Overture in G minor is one of several works he composed in 1716 as part of a successful campaign to obtain a position at the Dresden court of the art-loving elector Friedrich August of Saxony. “Overture” in this case refers not to an opera overture but to a freestanding orchestral suite; Veracini’s consists of three movements in the brilliant Italian style, followed by a heavily accented and slightly Germanic minuet. The majestic Largo makes effective use of contrasts between strings and oboes in alternating sections. Hasse’s “tragic intermezzo” Piramo e Tisbe, first produced in 1768, is based on Ovid’s tale of two young lovers who are torn asunder by their feuding families; he considered it one of his best works. When Thisbe informs Pyramus that her father is implacably opposed to their match, he gallantly attempts to boost her spirits in the energetic aria “Ah! non è ver, ben mio” (Ah! It is not true, my beloved). Like all the arias on this program, Hasse’s is cast in rounded da capo form, with the first part repeated in an ornamented version after a contrasting middle section. Although a mere quarter of a century separates Wassenaer’s elegantly crafted Concerto armonico in F minor from Veracini’s Overture, their modes of expression, or Affekt, could hardly be more different. Wassenaer, like Hasse, embraced the melodious, light-textured galant style that would come to dominate European music in the second half of the 18th century. The Concerti armonici were first performed at intimate house concerts in The Hague attended by a coterie of music-loving aristocrats in the composer’s elite circle of friends, among whom the emerging style was much in vogue.

Siroe, re di Persia (Siroe, King of Persia) was an early fruit of Vinci’s collaboration with the celebrated librettist Pietro Metastasio. Premiered in Venice in 1727, the opera inspired Vivaldi, Handel, Hasse, and other composers to make their own settings of Metastasio’s text. In “Gelido in ogni vena” (Icy cold in every vein), Siroe’s father, King Cosroe, believing him to be dead after wrongly accusing him of disloyalty, vents his grief in appropriately tremulous, bone-shivering tones. The composer Johann Joachim Quantz, who was on hand for the first performance, praised the tenor Giovanni Paita for resisting the temptation to the embellish Vinci’s music with superfluous passaggi.

Vivaldi’s Orlando furioso drew on another popular source of operatic plots: Ludovico Ariosto’s early–16th century poem about the exploits of the legendary Christian knight Roland. (Handel, Hasse, and Scarlatti also wrote Orlando operas.) The first of Vivaldi’s multiple treatments of the story, dating from 1714, was in fact a reworking of an opera by a lesser-known composer. Some of his music is lost, but among the surviving gems is the sparkling coloratura aria “Ah, fuggi rapido” (Ah, flee quickly), in which the hero’s cousin Astolfo exhorts Ruggiero, a Saracen knight, to flee the evil sorceress Alcina. Handel’s Ariodante, a later spinoff of Ariosto’s epic, stoked the craze for Italian opera seria that he had kindled years earlier with Rinaldo. Composed in 1735, the opera marked the composer’s debut at Covent Garden, where the impresario John Rich had set up a new opera company to compete with the upstart Opera of the Nobility at the King’s Theatre. One of the attractions Rich introduced was a resident French-style ballet troupe, which Handel obligingly featured in Ariodante: his arresting Overture begins with a stately preamble in dotted rhythm and ends with a vigorous gavotte. Like Handel, Scarlatti acquired a taste for the concerto grosso, a novel musical genre originating in Italy that pitted two groups of instruments against each other in a kind of amicable competition. His Concerto in C minor is the second of six such works scored for seven players: a solo concertino group (two violins and cello) and a larger ripieno ensemble (two violins, viola, and continuo). The interplay between the two groups generates an arresting panoply of textures.

In 1757, Handel (or, more likely, his associates, given his near-blindness and generally declining health) revised his 1737 oratorio Il trionfo del Tempo e della Verità (The Triumph of Time and Truth) for a performance at Covent Garden. The protagonists of this musical allegory, which was advertised as having been “Altered from the Italian with several new Additions,” are Beauty, Pleasure, Truth, and Time. In the aria “Guardian Angels,” Beauty avows her allegiance to Truth, declaring, “Let no more this world deceive me, / Nor let idle passions grieve me”—a sentiment seconded by the chorus in the final “Alleluja.” Handel was an inveterate recycler of his own and other composers’ music. His first set of Concerti grossi Op. 3, published in London in 1734, incorporated several individual movements that he had written at various times, and for different purposes, over the preceding two decades. When he returned to the genre five years later, however, Handel took no such shortcuts: all twelve of the Op. 6 Concertos were created from scratch in a month-long burst of inspiration in the fall of 1739. Their dazzling variety and exalted invention—as exemplified by the Concerto grosso in G major—made them as popular in Handel’s time as they are in ours. The program ends with another excerpt from Ariodante. Covent Garden’s enterprising impresario had scored a coup by engaging Giovani Carestini to sing the title role, and Handel highlighted the renowned castrato’s virtuosity in the bravura aria “Dopo notte, atra e funesta” (After a dark and gloomy night), in which a jubilant Ariodante celebrates the happy resolution of the many convoluted twists and turns of the opera’s plot.

A former performing arts editor for Yale University Press, Harry Haskell is a program annotator for Carnegie Hall in New York, the Brighton Festival in England, and other venues, and the author of several books, including The Early Music Revival: A History, winner of the 2014 Prix des Muses awarded by the Fondation Singer-Polignac.

A page from the score of Johann Adolf Hasse’s Piramo e Tisbe prepared for the 1768 premiere in Vienna (Austrian National Library)

„Der verständigste der jetzt lebenden Komponisten“

Falls noch ein Zweifel daran bestehen sollte, dass die europäische Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts immer eine stark internationale und kosmopolitische Note hatte, dann sollten die Biografien der Komponisten des heutigen Konzerts ihn ausräumen. An erster Stelle sind dabei Georg Friedrich Händel und Johann Adolf Hasse zu nennen, die in der Welt der Oper über Jahrzehnte hinweg den Ton angaben.

Essay von Michael Horst

„Der verständigste der jetzt lebenden Komponisten“

Barocke Opernarien und Instrumentalwerke

Michael Horst

Falls noch ein Zweifel daran bestehen sollte, dass die europäische Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts immer eine stark internationale und kosmopolitische Note hatte, dann sollten die Biografien der Komponisten des heutigen Konzerts ihn ausräumen. An erster Stelle ist dabei Georg Friedrich Händel zu nennen, der als gebürtiger Hallenser zuerst in Italien für Aufsehen sorgte, um schließlich in London über Jahrzehnte hinweg den musikalischen Ton anzugeben. Nicht weniger prominent, zumindest zu Lebzeiten, war der aus Bergedorf (heute ein Stadtteil von Hamburg) stammende Johann Adolf Hasse, der nach großartigen Erfolgen in Italien an den Dresdner Hof wechselte und später lange Jahre in Wien wirkte, dabei aber seine Verbindung zu Venedig nie aufgab und dort auch 1783 gestorben ist. Seine Oper Piramo e Tisbe von 1768 ist das jüngste der heute erklingenden Werke, die insgesamt einen Zeitraum von gut 40 Jahren umfassen.

In entgegengesetzter (Reise-)Richtung war Francesco Maria Veracini unterwegs. Aufgewachsen und ausgebildet in Florenz, machte er schnell Karriere als brillanter Geiger und kam 1717, mit 27 Jahren, als Kammerkomponist für den musikliebenden Sohn Augusts des Starken nach Dresden, wo er aufgrund seines exzentrischen Charakters für allerlei Aufsehen sorgte. Der Musikschriftsteller Charles Burney fällte ein wenig schmeichelhaftes Urteil: Veracini habe einen „so verblendeten Hochmut“ besessen, „daß er häufig prahlte, es gebe nur einen Gott, und einen Veracini“. Bis heute ungeklärte Zwistigkeiten mit dem Hofkapellmeister Johann David Heinichen und dem Kastraten Senesino sollen die Ursache für einen (glimpflich verlaufenen) Fenstersturz gewesen sein, nach dem Veracini jedoch das Weite suchte und sich in London niederließ.

Noch in Venedig hatte er den sächsischen Kurprinzen kennengelernt; vielleicht war es gerade die frisch komponierte Ouvertüre Nr. 6 gewesen, die das lukrative Angebot für Dresden zur Folge hatten. Die besonderen Fähigkeiten Veracinis treten in diesem Werk jedenfalls aufs Beste zutage. Eigentlich wäre die Bezeichnung Sonate passender, besteht es doch aus vier eigenständigen (kurzen) Sätzen kontrastierenden Charakters. Das einleitende Allegro präsentiert sich quasi als Wettstreit zwischen Streichern und Holzbläsern, das folgende Largo dagegen verströmt die idyllische Stimmung einer Schäferszene. Die geballte Energie, mit der das zweite Allegro voranstürmt, mündet zuletzt überraschend in ein Menuett, das von Streichern und Bläsern komplett im Unisono zu spielen ist.

Musikdramatische Verwicklungen

Neun Jahre jünger als Veracini war Johann Adolf Hasse, den Charles Burney noch 1772 in Wien besuchte; anschließend fasste er den europäischen Ruhm des Komponisten kurz und knapp zusammen: „Hasse ist der verständigste, natürlichste und eleganteste der jetzt lebenden Komponisten, […] er ist gleichermaßen ein Freund der Poesie und des Gesanges.“ Damals stand der Deutsche, dessen Werkverzeichnis Opern ebenso wie Messen und Instrumentalkonzerte enthält, allerdings schon weitgehend am Ende seiner Karriere. Den krönenden Abschluss seines Opernschaffens markierte Piramo e Tisbe, komponiert 1768, im Todesjahr Veracinis. Für weitere Aufführungen zwei Jahre später im Beisein der kaiserlichen Familie – Maria Theresia war Gesangsschülerin Hasses gewesen – entstand eine stark überarbeitete Fassung, die 1771 auch in Potsdam gespielt wurde. (In Berlin erklang das Werk erst kürzlich im Mai 2024 mit der Akademie für Alte Musik in einer konzertanten Aufführung, die Grundlage einer CD-Einspielung war.)

Das im Untertitel als „Intermezzo tragico“ bezeichnete Werk schildert die aus Ovids Metamorphosen wohlbekannte Liebesgeschichte von Pyramus und Thisbe: Von Thisbes Vater aufgrund einer Familienfehde an der Vereinigung gehindert, beschließt das Paar, im Dunkel der Nacht zu fliehen. Die folgenden musikdramatischen Verwicklungen, einschließlich der vermeintlichen Tötung Thisbes durch einen Löwen, enden mit dem Tod der Liebenden als Verkettung tragischer Missverständnisse. Im ersten Akt fordert Pyramus seine Geliebte auf, mit ihren Tränen den Vater zum Einlenken zu bewegen: „Ah! non è ver, ben mio“ (Ach, es ist nicht wahr, meine Geliebte). Hasses Musik zeigt, dass er die Zeichen der neuen Zeit, wie sie etwa in Glucks Orfeo ed Eurdice von 1765 zu hören waren, durchaus erkannt hatte: Zwar werden zentrale Wörter wie „piangere“ (weinen) immer noch kunstvoll mit Koloraturen ausgeschmückt, doch insgesamt klingt auch hier die neue Empfindsamkeit durch, die bald darauf in Mozarts Opern zum neuen Maßstab werden sollte.

Komponist in Adelskreisen

Dass die Musikgeschichte bisweilen auch veritable Krimis zu bieten hat, zeigt der Fall des niederländischen Komponisten Unico Wilhelm van Wassenaer. Gerade einmal 45 Jahre ist es her, dass die Urheberschaft der Concerti armonici, deren fünftes im heutigen Konzert zu hören ist, zweifelsfrei dem Adeligen aus der Provinz Overijssel zugeschrieben werden konnte. Zwar waren die Werke bereits 1740 in Den Haag publiziert worden, allerdings nur unter Nennung des dort ansässigen Geigers Carlo Ricciotti als Herausgeber. Im 19. Jahrhundert wurden die Concerti dann Giovanni Battista Pergolesi zugeschrieben – was bis 1979 Gültigkeit behielt. War Graf Wassenaer mit seinen Kompositionen unzufrieden gewesen und hatte es deshalb vorgezogen, anonym zu bleiben? Aus handschriftlichen Anmerkungen am Rand der Partituren jedenfalls wird ersichtlich, dass er sich lange gegen eine Publikation der Concerti gesträubt hatte. Sicherlich war es seinerzeit auch in niederländischen Adelskreisen alles andere als üblich, sich ernsthaft mit dem „Handwerk“ des Komponierens zu beschäftigen; andererseits wurde der Graf, über seine erfolgreiche Tätigkeit als Diplomat hinaus, für seine musikalischen Fähigkeiten als Instrumentalist durchaus geschätzt.

Unbeantwortet bleibt auch die Frage, wo und wie Wassenaer seine kompositorischen Fähigkeiten erlangt hatte. Als junger Mann unternahm er die übliche „Grand Tour“, die ihn sehr wahrscheinlich auch nach Italien führte und ihm verschiedenste musikalische Eindrücke bescherte. Seine Concerti armonici weisen in jedem Fall auf das römische Vorbild mit vier Violinen hin, wie es in den Werken von Corelli und Locatelli gepflegt wurde. Auch im Concerto armonico Nr. 5 f-moll haben erste und zweite Violinen zumeist die musikalische Oberhand. Schon der zweite Satz aber ist mit seinem Fugencharakter sehr viel gleichberechtigter strukturiert. Der dritte lässt die Instrumentengruppen nacheinander kanonisch zu Wort kommen, wobei das siebenstimmige Geflecht eine meisterliche Beherrschung kontrapunktischer Satztechnik beweist. Doch nicht das gesamte Werk ist von barocken Modellen geprägt – Momente des galanten Zeitalters sind unüberhörbar. Insofern erscheint die irrige Zuschreibung an Pergolesi nicht als völlig aus der Luft gegriffen.

Lieblingsstoffe und Erfolgsgeschichten

Der neapolitanische Komponist Leonardo Vinci – selbstverständlich nicht zu verwechseln mit dem Maler- und Erfindergenie ähnlichen Namens – hat in seinem (kurzen) Leben Italien nie verlassen. Doch welche Anerkennung er in seiner Heimat genoss, zeigt die Tatsache, dass allein um die Jahreswende 1725/26 drei neue Opern von Vinci uraufgeführt wurden, eine in Neapel selbst, eine in Rom und schließlich Siroe, re di Persia im Februar 1726 in Venedig. Das Werk war seine erste Zusammenarbeit mit dem aufgehenden Stern unter den Librettisten, Pietro Metastasio. Die verwickelte, intrigenreiche Geschichte um den persischen König Cosroe und seine Söhne Siroe und Medarse sollte zu einem Erfolgsmodell des 18. Jahrhunderts werden. Vinci war der erste in einer langen Reihe von mehr als 35 Komponisten, die im Laufe der folgenden Jahrzehnte dieses Libretto vertont haben, darunter auch Händel, Vivaldi sowie – gleich zweimal im Abstand von 30 Jahren! – Johann Adolf Hasse. Die ausgedehnte Arie des Vaters Cosroe „Gelido in ogni vena“ (Wie Eis fließt mir das Blut) zeigt Vincis Fähigkeit, über einem gleichmäßig pulsierenden Fundament schönste melodische Bögen zu spannen.

Einen scharfen Kontrast bildet, als Abschluss des ersten Konzertteils, die kurze, aber koloraturenreiche Arie des Astolfo „Ah, fuggi rapido“ (Ach, flieh schnell) aus Antonio Vivaldis erster, 1714 entstandener Vertonung von Orlando furioso (der 1727 eine weitere, berühmtere Fassung folgen sollte). Aus Ariosts 1516 erstmals veröffentlichtem Versepos um den mittelalterlichen Ritter Roland, die Zauberin Alcina und ihre sagenhafte Insel sind zahllose Operntextbücher hervorgegangen, die zu den Lieblingsstoffen vieler Komponisten im 18. Jahrhundert zählten, darunter Lully, Rameau und Haydn – sowie Händel mit seinen drei Opern Orlando, Alcina und Ariodante.

Londoner Meister

Die Ouvertüre zu Ariodante eröffnet dann auch der zweiten Teil des heutigen Programms. Händel vertonte hier eine Nebengeschichte zum „Rasendem Roland“, in der es um den schottischen Ritter Ariodante und die Königstochter Ginevra geht. Ariodantes Arie „Dopo notte, atra e funesta“ (Nach dunkler und unheilvoller Nacht), zu hören am Ende des Konzerts, ist eine der fünf Solonummern, die Händel für seinen neuen Star in der Titelrolle, den Kastraten Carestini, komponierte. Dementsprechend zahlreich sind die Koloraturen, Sprünge und weiten Melodiebögen, die in der Wiederholung des A-Teils noch eine weitere virtuose Steigerung erfahren.

Das Oratorium The Triumph of Time and Truth ist die dritte und letzte Version jenes Textes, den der junge Händel schon 1707 in Rom unter dem Titel Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno vertont hatte. Inwieweit der nahezu erblindete Komponist 1757, zwei Jahre vor seinem Tod, noch an der Neufassung beteiligt war oder seinen Schüler und Assistenten John Christopher Smith mit der Ausarbeitung betraut hatte, bleibt unklar. Die Arie „Guardian angels“ (Ihr Schutzengel) ist der allegorischen Figur der „Beauty“ (Schönheit) anvertraut – eine Adaption der ursprünglichen Arie „Tu del ciel eletto ministro“, in welcher der elegische Gesang statt von einer Violine nun von einer Oboe umspielt wird.

Hinter Händels Ruhm als Opernkomponist tritt seine Instrumentalmusik bisweilen in den Hintergrund. Dabei zeigen gerade seine Concerti grossi op. 6 von 1740 eine Vielfalt und unerschöpfliche Fantasie des Ausdrucks, die das Vorbild Arcangelo Corelli weit übertrifft. Das Concerto grosso G-Dur op. 6 Nr. 1 bildet sozusagen das gewichtige Eingangstor zu der zwölfteiligen Sammlung – Händel zieht schon hier musikalisch alle Register, vor allem mit den Echowirkungen zwischen Solo und Tutti, den markanten Steigerungen und dem quirligen Wechselspiel der Beteiligten. Der dritte, langsame Satz steht ganz im Zeichen der Soloinstrumente, der vierte Satz ist als Fuge angelegt, während eine leichtfüßige Gigue das Concerto als fünften Satz beschließt.

Mit London ist auch Alessandro Scarlattis Concerto Nr. 2 c-moll aus den Six Concertos in Seven Parts eng verbunden. Allerdings war der Italiener, der vor allem in Rom und Neapel wirkte, bereits 15 Jahre tot, als die Werke an der Themse fast gleichzeitig mit Händels Opus 6 erschienen – die einzige gedruckte Sammlung von Instrumentalmusik aus seiner Feder überhaupt. Es erstaunt nicht, dass Scarlatti das bewährte Modell Corellis übernimmt, hatte er mit diesem doch kollegial für die im römischen Exil lebende Königin Christina von Schweden zusammengearbeitet. Allerdings war Scarlatti eine Generation älter als die übrigen Komponisten des heutigen Programms, insofern wirkt auch sein Concerto im Vergleich zu Händel deutlich „altmodischer“; die Kontraste zwischen Solo und Tutti werden längst nicht so stark herausgearbeitet. Stattdessen herrscht – der Tonart f-moll entsprechend – ein pathetischer Tonfall vor, der im Largo, dem dritten und längsten Satz, besonders expressiv ausgestaltet wird.

Der Berliner Musikjournalist Michael Horst arbeitet als Autor und Kritiker für Zeitungen, Radio und Fachmagazine. Außerdem gibt er Konzerteinführungen. Er publizierte Opernführer über Puccinis Tosca und Turandot und übersetzte Bücher von Riccardo Muti und Riccardo Chailly aus dem Italienischen.

The Artists

Roberta Mameli

Soprano

Born in Rome, Roberta Mameli studied voice and violin at the Conservatorio di Musica Giuseppe Nicolini in Piacenza and completed her education in master classes with Bernadette Manca di Nissa, Ugo Benelli, Konrad Richter, Claudio Desderi, and Enzo Dara. She is a regular guest at the most prestigious concert halls and opera houses including the Vienna Konzerthaus and Theater an der Wien, Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Cité de la Musique in Paris, Gran Teatre de Liceu in Barcelona, and London’s Wigmore Hall. She has appeared with conductors such as Jordi Savall, Christopher Hogwood, Fabio Biondi, Ton Koopman, and Claudio Abbado, among many others. An Early-Music specialist, Roberta Mameli regularly collaborates with ensembles such as Accademia Bizantina, Le Concert des Nations, La Venexiana, Europa Galante, and I Barocchisti. In 2018 she made an acclaimed appearance at Berlin’s Staatsoper Unter den Linden in the title role of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea together with the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin. Further highlights include Belinda in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and the title role of Leonardo Vinci’s Didone abbandonata. She sang Aci in Handel’s Aci, Galatea e Polifemo at the Bucharest Enescu Festival, London’s Wigmore Hall, as well as in November 2023 at the Pierre Boulez Saal, where she has since appeared in various different programs.

January 2026

Bernhard Forck

Concertmaster and Musical Director

Bernhard Forck studied violin with Eberhard Feltz at the Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin and began his career as a member of the Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester (today’s Konzerthaus Orchestra). He received important guidance in the field of Early Music and historically informed per formance from Nikolaus Harnoncourt at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, among others. As one of the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin’s concertmasters, he regularly performs in major musical centers across Europe and has toured the Middle East, Japan, Southeast Asia, Australia, and North and South America. He is also a member of the Berliner Barock Solisten and performs music of later centuries, in particular of the Second Viennese School, with the Manon-Quartett Berlin, which he founded. Bernhard Forck teaches at the Hanns Eisler School of Music, among other institutions, and worked closely with the orchestra of the Halle Handel Festival for many years, including as its music director from 2007 to 2019.

October 2025

Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin

Founded in 1982, the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin is among the world’s leading chamber orchestras for historically informed performance and appears across Europe as well as in Asia and the Americas. The ensemble has presented its own concert series at the Konzerthaus in Berlin since 1984 and regularly appears at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, enjoying a close artistic relationship with René Jacobs. The Akademie performs under the direction of its three concertmasters, Georg Kallweit, Bernhard Forck, and Mayumi Hirasaki. Other artists who have collaborated with the ensemble include conductors Emmanuelle Haïm, Bernard Labadie, Diego Fasolis, Rinaldo Alessandrini, and Francesco Conti as well as Isabelle Faust, Andreas Staier, Alexander Melnikov, Anna Prohaska, Carlo Vistoli, and Bejun Mehta, among many others. In addition to the music of the Baroque and Viennese Classical periods, the orchestra regularly performs 19th-century repertoire, such as Beethoven’s symphonies and, together with the RIAS Kammerchor, the early mass settings of Anton Bruckner and the oratorios of Felix Mendelssohn. The orchestra was awarded the city of Magdeburg’s Georg- Philipp-Telemann-Preis in 2006 and the Bach Medal of the city of Leipzig in 2014. For their recordings, the musicians have received a Grammy Award, Diapason d’Or, Gramophone Award, and ECHO Klassik. The Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin is a regular guest at the Pierre Boulez Saal, where its recent performances include the staged production of Handel’s Aci, Galatea e Polifemo in 2023 and the complete orchestral works of Emilie Mayer in October 2025.

January 2026

Barenboim-Said Akademie

Since 2015, talented young musicians from the Middle East, North Africa, and other countries have been studying at the Barenboim-Said Akademie, a new institution of higher music education in Berlin. Regular teaching activities for up to 90 students began in the fall of 2016 with a four-year bachelor program that includes a stronger focus on the Humanities and musicology than is common in professional music education. A master program was added starting in 2024. The Barenboim-Said Akademie’s central idea is expressed in a spirit of inclusion and diversity: through playing and listening, students learn to accept differences, to engage in discussion with an open mind and an open heart, and to discover the humanistic ideals of the Enlightenment. The Akademie, which shares its building with the Pierre Boulez Saal, is dedicated to the pedagogical spirit of Edward W. Said and Daniel Barenboim, which tries to overcome ideological trenches. With its unique, innovative academic offerings, the Akademie keeps alive a dialogue that stands up to the political upheaval of the contemporary world.