Ali Ghamsari Tar

Saba Pashaee Voice

Ruven Ruppik Percussion

Mohammad Jaberi Daf

Program

Mahoor

Tar Solo

Charmezrab

Zendegi

Beranid

Intermission

Motrebe Khosh Nava

Tar Solo / Avaz

Suite of Iranian Folk Songs

Negara

Zakhme o Zakhm

All compositions by Ali Ghamsari

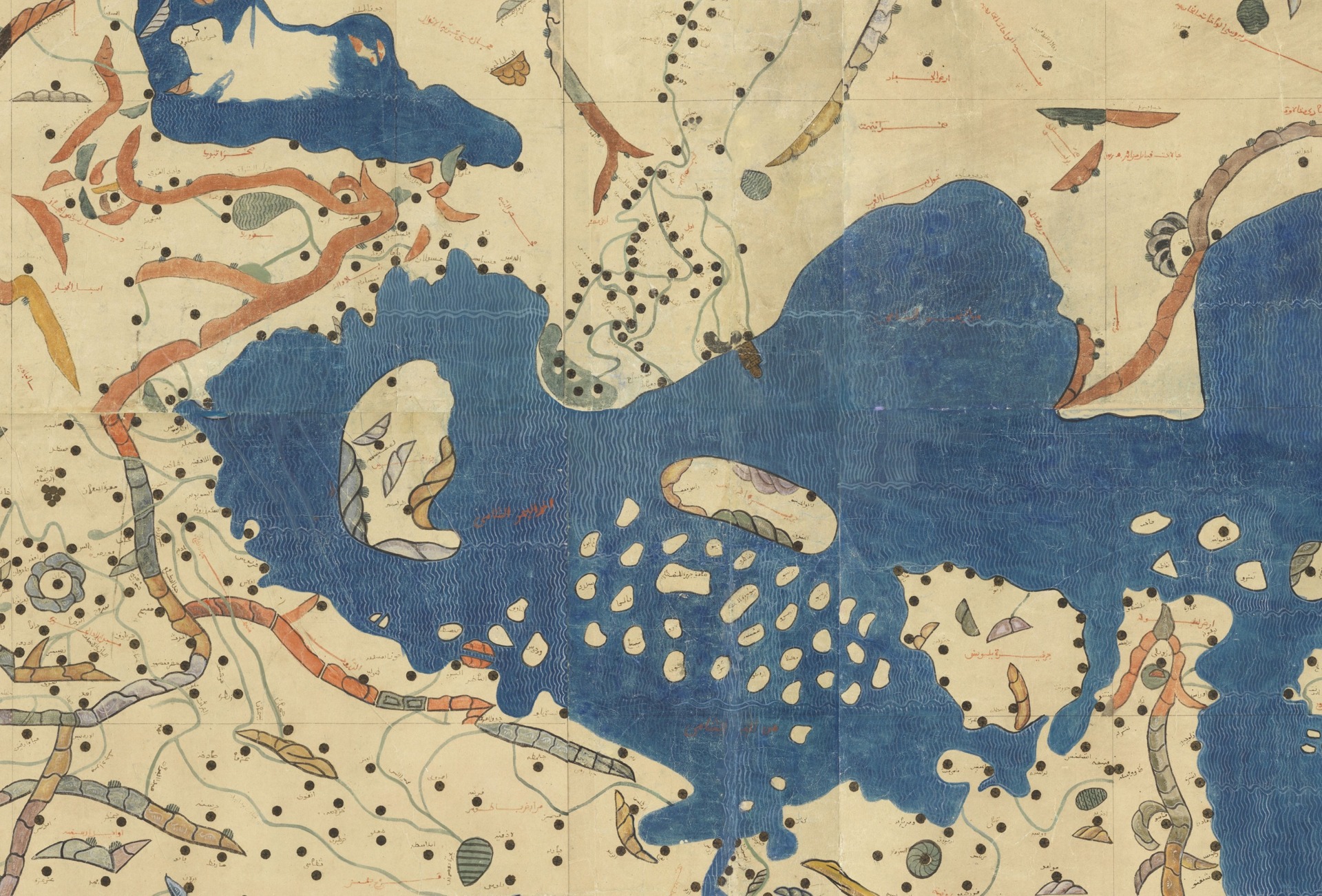

Detail from Muhammad Al-Idrisi’s map of the world (oriented to the south), created for Roger II of Sicily around 1154, showing the eastern mediterranean with the Greek peninsula in the bottom right corner (19th-century reproduction) (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The Journey of Instruments

As one of the oldest musical instruments known to humanity, the oud has become an essential element of different musical cultures, not just in the Middle East and Northern Africa but also in other parts of the world that were touched by it through waves of migration, cultural exchange, and trade. The journey of the oud highlights a cultural pathway that reflects the interaction and communication between peoples.

Introduction by Naseer Shamma

The Journey of Instruments

As one of the oldest musical instruments known to humanity, the oud is a prominent symbol of musical civilization across the Middle East. Archaeological evidence indicates that the earliest reference to a lute dates back to the Akkadian era, around 2350 BCE, where the instrument appeared in carvings and murals in Mesopotamia. Since that ancient time, the oud has remained an essential element of different musical cultures, not just in the Middle East and Northern Africa but also in other parts of the world that were touched by it through waves of migration, cultural exchange, and trade.

Reaching far beyond the transfer of a musical instrument from one country to another, the journey of the oud highlights a cultural pathway that reflects the interaction and communication between peoples. Along the way, the instrument demonstrates the power of art to transcend borders, adapting to diverse musical styles—from Eastern maqamat to Western scales, from Sufi chants to folk music.

The oud emerged in a rich cultural environment of musical innovations where it was part of the artistic scene in temples, palaces, and marketplaces. Its simple construction—a pear-shaped body, short neck, and gut strings—made it practical and portable, aiding its spread through trade routes and military expeditions. Over time, it took on new shapes and names, such as the Turkish bağlama, the Persian tar, the Greek bouzouki, the Italian mandolin, or the Spanish guitar. A part of this story is reflected in the five concerts presented this season at the Pierre Boulez Saal.

In Iraq, we hear the oud in its natural environment, telling the tales of Mesopotamia. In Iran, we witness the interaction with the tar and other Persian instruments, reflecting mutual influence. In India, we discover how the oud’s spirit extended into the sitar, in a fascinating historical continuation. In Spain, we see how flamenco redefined the Middle Eastern sound within a Mediterranean context. We conclude the journey in Central Europe with the lute of the Baroque era.

These concerts are not just performances—they are meetings with time, where melodies blend with history. This series is an invitation to dive into the story of the oud as an instrument and as a bridge between civilizations. Studying it reveals the unity of the human experience and helps us understand that the strings once plucked by an Akkadian musician 4,000 years ago still resonate today.

Welcome to the Journey of Instruments!

—Naseer Shamma

Illustration for the Tale of Ibrahim and the Singer from Zakariya al-Qazwini’s Book of Wonders of Creation and Unique Phenomena of Existence, Persia, 13th-14th century (Staatsbibliothek Berlin)

A Universal Instrument

An instrument as celebrated and revered as the oud must have had, or so one would think, a fabulous origin. Various traditions attribute the invention of the precursors of all lute instruments to the Prophet Mohammed, the Greek philosopher Pythagoras, or Lamech, the son of Methuselah and father of Noah.

Essay by Jean During

A Universal Instrument

A Brief History of the Oud

Jean During

Mythical Origins

An instrument as celebrated and revered as the oud must have had, or so one would think, a fabulous origin. According to one tradition, it was the Prophet Muhammad who made the first lute, but it did not produce any sound because it lacked a bridge and a nut, which connect the strings to the instrument’s body. Satan then came to his aid by adding these two essential elements. The lute had a pleasant sound, but the Prophet would not play it because it had been touched by Satan.

The 17th-century Indo-Persian medical encyclopedia of Nureddin Muhammad Shirazi recounts how the Greek philosopher Pythagoras created the precursor to all lute instruments. While in the jungle, he discovered the body of a dead monkey whose guts, stretched between the branches, produced sounds when the wind blew through them. Pythagoras then pulled the monkey’s skin over a coconut to make the first lute. A similar story exists in Chinese Turkestan and in India. It is reminiscent of yet another version, in which the invention of the lute is attributed to Lamech, the son of Methuselah and father of Noah. According to the 9th-century writer Ibn Khordadbeh, the instrument was created from the dismembered body of Lamech’s son, which he found hanging in a tree. By this tradition, the lute’s body imitated the thigh; the tailpiece, the foot; the fingerboard, the ankles; and the strings, the blood vessels. Lamech proceeded to draw sounds from the instrument and sang a lament.

Ancestors

Before the appearance of the barbat, the main precursor of the oud, around the 2nd century BCE, the most widespread lute for more than 2,000 years had been the spike lute. Still in use south of the Sahara, it has a rounded neck that crosses the skin of the soundboard, to which the strings are attached. A sub-Saharan variant, similar to ancient Egyptian and Hittite lutes, is played by plucking the strings with the fingers. Another version of the spike lute with a skin top, used by the Amazighs of Morocco, has a pear-shaped body with three or four strings that are struck with a plectrum, like an oud. The pre-Islamic Arab lute probably belonged to this category, before being eclipsed by the barbat.

The oldest pictorial representations of the barbat, which most likely originated in Central Asia, date back to the 1st century BCE and were found in present-day southern Uzbekistan and northern Tajikistan. The instrument does not appear in north-west India until the 1st century CE and was probably in use in Persia a few decades later. By then widespread throughout the Middle East and Central Asia, the barbat was adopted by the Arabs of the Hijaz, the Western part of the Arabian Peninsula, around 600 CE. A version with four double strings known as the kwitra (from which the word “guitar” originates) is still in use today in Morocco and Algeria.

In its eastward migration, the barbat gave rise to the Chinese pipa and the Japanese biwa, instruments that are close to their origins, as attested by the etymology of their names (with barbat sinicized first to pipa, then to biwa). Culturally, the barbat survived for centuries in classical poetry as a trope evoking the golden age of Persian music.

The instrument’s main innovation was to carve the body and neck from a single piece of wood and attach a wooden soundboard instead of using parchment—a time-consuming process that required a large amount of wood. By comparison, the body of the oud is made from glued wooden strips, with the neck separate from the body, two technical features still found in most long-necked lutes today. Iranian iconography attests to the barbat’s use until the 10th century, and a court musician of the 11th century was still nicknamed barbati, not oudi. Yet with its bigger, deeper, more rounded, glued-slat body and the addition of another string (or the doubling of the existing ones), the oud was both lighter and sounded louder than its predecessors—a new instrument was born. By the 14th century, the barbat had almost completely disappeared from the Middle East, having been replaced by the so-called “perfect” oud (kamil) with five double strings; a later improvement was the “most perfect” oud (akmal) with an additional low string. The term oud itself may come from the Pehlevi words barbud (“string”) or rud (“lute”). In Arabic, oud means “rod” or “stick,” which has no connection to a lute, despite what is often said. [Another etymology proposes that rod or stick by extension can also mean “wood,” thus describing the instrument’s body. Editor’s note.]

Playing Technique

The ancient descriptions of the Arabic oud are so precise that it has been possible to construct an instrument identical to its 14th-century variant. We know from the 9th-century philosopher and music theorist al-Kindi that the barbat had four strings made of silk, a feature retained by the pipa and the biwa, while for the oud gut strings became the norm (commonly replaced today by synthetic materials that are less sensitive to hydrometric variations). When describing a string instrument, it is essential to keep in mind that the playing technique is often more important than the shape and materials. The pipa, for example, looks very similar to the biwa, but the latter is played with a large triangular plectrum, producing completely different sounds and effects. Similarly, the European lute is plucked with the fingertips, while the oud is played with a plectrum.

The question of whether the ancient oud was fretted has recently been settled by a substantial body of scholarship. The semi-conical shape of the neck, the reduced space between the string plane and the fingerboard, and the untempered scales based on small variations in intonation all make the fretting theory unrealistic. An ancient anecdote recounts one of the famous early lute masters being challenged to play on a detuned instrument. He easily overcomes this obstacle and reproduces the melody perfectly, which would only be possible on a smooth neck without frets. (Conversely, frets are essential for harmony-based and polyphonic music, and their precise positioning was the subject of detailed study during the European Baroque.)

To Europe

Following the Arab conquest of the Iberian Pensinsula, which began in 711, many Middle Eastern instruments were adopted in the Christian world. The earliest known European depiction of a lute can be found in a sculpture in the Cathedral of Jaca in Aragon, which dates from the late 11th century. Around 1280, an oud was depicted in the Spanish musical manuscript of the Cantigas de Santa Maria. This instrument had nine strings, probably four pairs plus one, and is still played with a plectrum. Over the course of the 14th century, the lute began to spread throughout the rest of Europe and remained a primary instrument for more than 300 years, undergoing numerous modifications and mutations. Curiously, it disappeared around 1780, to be replaced by the guitar, but made a reappearance in the 20th century. The earliest European lutes are characterized by their lightness and the type of wood used, with the slats forming the instrument’s body often reduced to a thickness of just one millimeter. This makes them extremely fragile, so very few have survived from the huge number produced. Another notable feature is that these instruments were plucked with several fingers to meet the needs of polyphony and counterpoint.

While the members of the oud family evolved into many national and local varieties, a general tendency throughout its history was to add strings and to increase the instruments’ size and volume. Persian miniatures from the 16th and 17th centuries show an enormous shahrud, or “royal lute,” behind which the musician almost disappears. Around the same time, Italian instrument makers developed the theorbo or chitarrone, which has no fewer than 14 strings and can reach two meters in length.

In Turkey, the oud was replaced by the tanbur, while in Persia a different type of lute became prominent, later known as the tar. Its concept is quite distinct from the oud: it has a long neck, and its soundboard is made of thin parchment rather than wood. Metal strings have replaced gut or silk, giving it a brilliant tone enhanced by more sophisticated plectrum techniques.

The Oud Today

When it comes to serving the modal complexity of classical maqam, however, the oud remains unrivalled. This is particularly true in the Arab world, where it has never relinquished its throne. At the beginning of the 20th century, it regained favor with Turkish musicians, and during the same period the lute experienced a revival in Northern Europe thanks to the rediscovery of Baroque and Renaissance music. In Iran, the oud was believed to have been abandoned for several centuries, but a fresco hidden in a corridor of the Golestan Palace in Tehran shows a courtesan holding one around 1830. After a tentative reappearance in the 1960s, the instrument experienced a resurgence in popularity in the 2000s.

Today, different styles of oud construction can be distinguished throughout the Middle East and Northern Africa, including in Egypt, Syria, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Morocco. Over time, the oud has become as universal as the violin.

Prof. Jean During is emeritus research fellow at the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris. His fieldwork covers several musical traditions of Central Asia as well as Sufi rituals. He has published 12 books on these musical cultures and numerous articles in scientific journals and encyclopedias. His approach relies upon a thorough practice of Middle Eastern music. In 2016, he received the Ziryab Prize from the Tunisian Ministry of Culture for his contribution to the study of Arabic music.

The “Journey of Instruments” concerts are being recorded as a co-production of the Pierre Boulez Saal and rbb in collaboration with ARTE Concert and will be released at a later date.

The Artists

Ali Ghamsari

Tar

Born in 1983, Ali Ghamsari studied at the Conservatory and the University in Tehran and is among today’s most distinguished and successful performers and composers of classical Persian music. In his works, which he has released on more than a dozen albums, he combines the radif tradition with contemporary elements. Concerts and tours as a soloist and with his own ensembles have taken him to many countries around the world. In addition to his main instrument, the long-necked lute tar, he plays setar, divan saz, and guitar. He also performs regularly with Naseer Shamma’s Peace Builders Group. Ali Ghamsari is the founder of the Institute of Persian Music in Tehran and teaches composition and music theory at Tehran University.

December 2025

Saba Pashaee

Vocals

Saba Pashaee is an Iranian singer and educator who has been performing and teaching Persian classical music for more than two decades. She began studying the radif repertoire at the age of 17 and also learned to play setar and tombak. After earning a master’s degree in Persian Literature, she decided to devote her life to music. Her collaborations range from leading the Ensemble Sarbang to performing with the Iranian National Orchestra at Vahdat Hall in Tehran, as well as participating in international events across Europe.

December 2025

Ruven Ruppik

Percussion

Ruven Ruppik initially trained as a percussionist in Western classical music, focusing on contemporary works and collaborating with artists such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Kurt Masur, Peter Eötvös, Martin Christoph Redel, and Jaap van Zweden, among others. At the same time, he pursued studies in the traditional music of the Balkan region. He subsequently attended the World Music program at Codarts University for the Arts in Rotterdam and received his Master of Music degree in classical North Indian music with Niti Ranjan Biswas and Hariprasad Chaurasia. Performances have taken him to the North Sea Jazz Festival, the Cairo Jazz Festival, and Drums’n’Percussion Paderborn. He teaches at the Zurich University of the Arts and at the Detmold Musikhochschule.

December 2025

Mohammad Jaberi

Daf

Mohammad Jaberi was born in 1981 in Kermanshah, Iran, and studied the frame drum daf with Khalife Karim Safvati and Ahmad Khaktinat at Tehran University. In concerts at home and abroad, he has performed with distinguished musicians including Shahram Nazeri, Jalal Zolfonun, Kambiz Roshanravan, Seyed Ali Jaberi, Parvaz Homay and the Mastan Ensemble, Sheida Jahed, Bijan Bijani, Mohammad Motamedi, and Seyed Jalaleddin Mohammadian. Now based in London, he has been heard at Festival de Carthage, Festival de Fès des Musiques Sacrées du Monde, Mawazine Festival, Expo Dubai, and the Ireland Music Festival, among many others.

December 2025