Renaud Capuçon Violin

Guillaume Bellom Piano

Program

Camille Pépin

Si je te quitte, nous nous souviendrons

for Violin and Piano

Maurice Ravel

Sonate posthume

for Violin and Piano in A minor

Rita Strohl

Solitude for Violin and Piano

Guillaume Lekeu

Sonata for Violin and Piano in G major

Camille Pépin (*1990)

Si je te quitte, nous nous souviendrons

for Violin and Piano (2022)

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Sonate posthume

for Violin and Piano in A minor (1897)

Intermisison

Rita Strohl (1865–1941)

Solitude for Violin and Piano (1897)

Lent. Doux avec un grand sentiment de tristesse

Guillaume Lekeu (1870–1894)

Sonata for Violin and Piano in G major (1892–3)

I. Très modéré – Vif et passioné

II. Très lent

III. Très animé

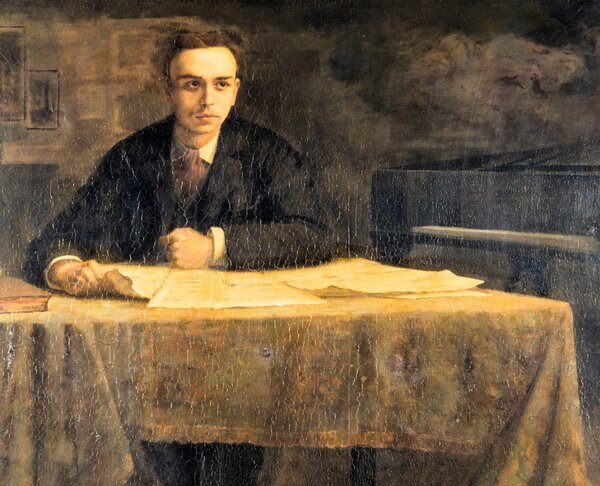

Guillaume Lekeu, portrait by Servais Detilleux (1896)

Francophone Moods

In their duo recital, Renaud Capuçon and Guillaume Bellom celebrate rarely heard music by French and French-speaking composers from the late 19th century to the present day.

Program Note by Harriet Smith

Francophone Moods

Music for Violin and Piano by Pépin, Strohl, Ravel, and Lekeu

Harriet Smith

Camille Pépin

Si je te quitte, nous nous souviendrons

In their duo recital, Renaud Capuçon and Guillaume Bellom celebrate rarely heard music by French and French-speaking composers from the late 19th century to the present day. The most recent work opens the program: Camille Pépin wrote Si je te quitte, nous nous souviendrons for these two artists, who gave its premiere in November 2023. Born in Amiens in 1990, Pépin has often been inspired by the written word, and this composition is no exception.

“My piece was inspired by the two last lines of Certitude,” she writes, “a poem by Paul Éluard. After evoking sweet moments spent with the beloved, the poet concludes: ‘If I leave you, we’ll remember each other. Parting, we’ll find one another again.’ These enigmatic lines cast a different light on the beginning of the poem: is this the end of the story? Could our memories keep the story alive in our hearts?

“The slow introduction states various motifs that will recur throughout the piece: the violin’s open fifth symbolizes the absence of the loved one; the piano slowly enunciates a nostalgic motif, like a mild regret. Various arpeggios and eerie bass lines develop a minimal, stripped-back aural landscape. A void. Remembering the loved one means facing the gaping hole left by his or her absence. The various elements begin to take shape. The movement starts with the regret motif in the piano part, transforming the material into a breathless, mesmerizing episode. Overlapping layers of instrumental motifs generate a lush soundscape where happy memories intertwine with the ambient melancholy. Over a repetitive keyboard texture, the sonic material becomes suddenly brighter. The violin twirls and swirls playfully around the dance-like, minimalist material. Happy memories finally break free and cast off their veil of sadness. Then the bright episode fades, and the piece reverts to its initial mood and sense of emptiness, leading to a short, nervous, anxious and tormented violin cadenza. Tremolos in the low register of the keyboard trigger a dramatic surge of energy and herald the return of the first rhythmic section. Both instruments now chant the motifs, reflecting both love and sadness, mixing all those memories as they run in the mind, blending together, hauntingly. The slow section finally reoccurs, apparently softer and more peaceful but not really. It is more like a question mark at the end of a love story that was beautiful, intense. Stormy.”

Maurice Ravel

Sonate posthume

For decades after his death in 1937, we knew only of a single violin sonata by Maurice Ravel—the mature three-movement masterpiece completed in 1927. When an earlier work was published in 1975 to mark Ravel’s centenary, it offered a fascinating insight into the young composer’s still-developing style. What continues to beguile about this one-movement work in the year of his 150th-birthday celebrations is the way that Ravel pours so much of his personality into a standard sonata-form movement, complete with exposition repeat. In fact, the piece sounds more like a rhapsody than a sonata, with the 22-year-old composer transcending the strictures of the form. He does this in various ways, beginning with the violin’s opening, which sets the tone, sounding initially hesitant, the key as uncertain as the time signature. The first bar in fact is in 7/8, but the opening phrase includes a triplet, which discombobulates the mind—a technique Ravel continues to employ throughout the rest of the movement with its constantly shifting time signatures.

There are also hallmarks already of the mature composer, such as Ravel’s fascination with the technical possibilities of any given instrument and a desire to push at those perceived limitations. As in many later works, he seems reluctant to allow the music to come to rest, always moving forward, which is partly achieved by reharmonizing the same motif, and partly through techniques such as the chromatically descending sequences of fifths in the piano writing. The textures are full of contrast, not least in the way the composer sets off into the development section with the most crystalline, high-register writing, and that sense of continuously molding the musical material continues right into the recapitulation, where Ravel’s boundless invention finally comes to rest in the closing moments.

Rita Strohl

Solitude

Rita Strohl’s name may have fallen into obscurity, but she must have been a force of nature. Born a decade before Ravel, she entered the Paris Conservatoire aged just 13 and was publishing her own music by the age of 19. But then Strohl was never going to be merely average, given the family into which she was born. Her mother was the groundbreaking painter known professionally as Élodie La Villette who, with her sister Caroline, was among the first woman painters to pursue an artistic career. The sisters continued to paint together after they were married, frequently exploring maritime themes.

At the Conservatoire, Rita Strohl studied piano and solfège, taking private lessons in composition and singing. Her earliest published works include piano trios and a Mass for six voices, showing her musical ambition. Unusually for her time, she was as attracted to Wagnerism as she was to Symbolism yet managed to avoid losing her sense of identity to either movement.

Strohl published Solitude for cello (or violin, as performed tonight) in 1897, the same year Ravel was writing his violin sonata. It is a song without words – four minutes of pure cantabile magic. The central section builds on the ardor of the opening mood, before the initial theme returns, but with a sense that the music and the mood are still developing, only calming emotionally at the closing chords. It is no wonder that the piece was admired by fellow composers such as Fauré, Duparc, Saint-Saëns, and d’Indy.

Guillaume Lekeu

Sonata for Violin and Piano

By the time Strohl and Ravel were composing their works, Guillaume Lekeu – of roughly the same age – had already been dead for three years. He died of typhoid fever in January 1895, just a day after his 24th birthday.

His gifts were prodigious, a fact his parents clearly recognized. Born in the Belgian village of Heusy, Lekeu received initial lessons at the local conservatory before the family moved to France, first to Poitiers when Guillaume was 9, and then to Paris in 1888, where he studied philosophy as well as taking private lessons with César Franck for two years. After Franck’s death, Vincent d’Indy took Lekeu under his wing, teaching him orchestration and encouraging him to enter the Belgian Prix de Rome, which he duly did, taking second prize in 1891 for his cantata Andromède.

In his brief composing life, which lasted only nine years, he produced over 50 works of astonishing sophistication and variety. From his first known piece, an unfinished Violin Sonata in D minor, Lekeu quickly proceeded to song settings, works for string quartet (some frustratingly lost), and a cello sonata. Within a few years he had turned his attention to the orchestra, with compositions inspired by Victor Hugo’s Les Burgraves and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. His last work was a Piano Quartet, completed by d’Indy after his death. But the Violin Sonata heard tonight remains his best-known work. Written at the age of 22, it was commissioned by the legendary Eugène Ysaÿe.

It is perhaps not surprising that the musical language of Lekeu’s Sonata should be distinctly Franckian, both in its heightened emotionalism and its use of the older composer’s cyclical technique as a means of linking the entire work together. Lekeu is writing on an ambitious scale –the piece lasts more than half an hour – and the sense of narrative drive and of constantly shifting emotions never flags. The violin writing shows off Ysaÿe’s peerless approach to rubato and his celebrated sound, but the piano part is just as demanding, with the two protagonists treated very much as equals. Two outer movements of virtuosity and energy frame a slow movement in which Lekeu spins a miraculous stream of melody in 7/8 time, the only contrast coming from an inner section with a simple song-like tune introduced by the piano. To be played “Très lent,” this is music full of poise and a sense of spaciousness that gives voice to the young composer’s emerging artistic personality.

Harriet Smith is a UK-based writer, editor, and broadcaster. She contributes regularly to Gramophone magazine and is a former editor of BBC Music Magazine, International Record Review, and International Piano Quarterly.

Camille Pépin (© Capucine de Chocqueuse)

Anfang und Ende

Rätselhafte Zeilen des symbolistischen Dichters Paul Éluard inspirierten Camille Pépin zu der Komposition, mit der Renaud Capuçon und Guillaume Bellom ihr Programm eröffnen. Die beiden französischen Künstler präsentieren außerdem selten zu hörende Werke von Rita Strohl, Maurice Ravel und Guillaume Lekeu.

Essay von Antje Reineke

Anfang und Ende

Werke für Violine und Klavier von Pépin, Strohl, Ravel und Lekeu

Antje Reineke

„Si je te quitte, nous nous souviendrons / En te quittant nous nous retrouverons.“ Ausgangspunkt von Camille Pépins Werk für Violine und Klavier sind zwei Verse aus dem Gedicht Certitude des surrealistischen Dichters Paul Éluard: „Wenn ich dich verlasse, werden wir uns erinnern / Indem ich dich verlasse, werden wir uns wiederfinden.“

„Diese rätselhaften Zeilen tauchen die vorausgehenden in ein anderes Licht“, kommentiert die Komponistin. In ähnlich paradoxen Wortspielen hatte Éluard zuvor eine intensive Liebesbeziehung gezeichnet. Ist der Abschied nun „das Ende der Geschichte“, fragt Pépin: „Reichen unsere Erinnerungen, damit sie in unseren Herzen weiterlebt?“

Sie brauche „etwas Außermusikalisches“, aus dem sie eigene Bilder entwickelt und in Musik setzt, erklärt die 34-Jährige aus Amiens, die bei Guillaume Connesson, Marc-André Dalbavie und Thierry Escaich in Paris studierte. Sie vergleicht sich mit einer Malerin: „Ich habe Vorstellungen von der Textur, der Farbe, der Mischung der Klangfarben, davon, wie ich eine Textur in eine andere verwandeln, wie ich das Material zum Klingen bringen, wie ich es verändern werde.“ Eine melodische Ausgangsidee, sagt sie, gäbe es dabei meist nicht. Als künstlerische Vorbilder nennt sie Steve Reich, John Williams, Debussy, Ravel und Bartók.

Der Anstoß zur Beschäftigung mit Éluard kam von Renaud Capuçon, für den Pépin zunächst das 2023 in Paris uraufgeführte Violinkonzert Le Sommeil a pris ton empreinte komponierte. Si je te quitte, nous nous souviendrons, das Capuçon und Guillaume Bellom gewidmet ist, folgte im November des gleichen Jahres in Aix-en-Provence.

Eine leere Quinte symbolisiert die Abwesenheit der oder des Geliebten. Das Klavier ergänzt ein „nostalgisches Motiv“, erklärt Pépin, wie eine „sanfte Sehnsucht nach Vergangenem“, das in mehreren Ansätzen Gestalt gewinnt. Es setzt mit dem „fehlenden“ Ton an, durch den eine melancholische Mollterz entsteht, und endet mit der leeren Quinte. Arpeggien und „mysteriöse Basstöne“ erzeugen eine „nüchterne, hohle Stimmung“. „Sich an den geliebten Menschen zu erinnern bedeutet, sich der Leere zu stellen, die seine Abwesenheit hinterlässt.“ Insofern belebt sich das Geschehen allmählich; die Motive verwandeln sich und legen sich in mehreren Schichten übereinander. Dabei „mischen sich glückliche Erinnerungen mit Macht unter die vorherrschende Melancholie“, bis sie schließlich in einer „plötzlich helleren“ Passage die Oberhand gewinnen. Doch dies ist nicht von Dauer und das Stück endet, wie es begonnen hat. Zwar wirkt es nun sanfter und ruhiger als zu Beginn – doch das täuscht, sagt Pépin und spricht von einem „Fragezeichen angesichts des Endes einer Liebesgeschichte, die schön und intensiv war. Bewegt.“

Mit einem Gefühl großer Traurigkeit

Rita Strohls Solitude (Einsamkeit) schließt hier thematisch direkt an. Das 1897 veröffentlichte Charakterstück für Violoncello oder Violine und Klavier mit dem Untertitel „Rêverie“ (Träumerei) ist ein ruhiger, eindringlicher Gesang in d-moll, „sanft, mit einem Gefühl großer Traurigkeit“ zu spielen. Der Mittelteil zeigt sich lebhafter und heller, und hier beginnt das Klavier, das anfangs vor allem begleitende Funktion hat, ebenfalls zu singen: eine Erinnerung wie bei Pépin? Oder eine Projektion der Sehnsucht nach Gemeinschaft?

Poetische Charakterstücke wie dieses waren im 19. Jahrhundert beliebt, gerade in den kulturell einflussreichen Pariser Salons. Doch für Strohls Schaffen ist das kleindimensionierte Solitude keineswegs repräsentativ. Die Komponistin aus der bretonischen Hafenstadt Lorient war die Tochter der Malerin Élodie La Villette und eines Offiziers und Amateurcellisten. 1878, mit 13, begann sie ein Klavierstudium am Pariser Konservatorium, wo sie in Prüfungen bereits eigene Kompositionen spielte. Gegen den dortigen Theorieunterricht rebellierte sie jedoch wie wenig später Maurice Ravel. Kompositionsunterricht nahm Strohl privat bei Adrien Barthe, einem ehemaligen Gewinner des prestigeträchtigen Prix de Rome – obwohl Frauen das Kompositionsstudium am Konservatorium seit 1850 offenstand. Strohl war zweimal verheiratet, und beide Ehemänner unterstützten ihre künstlerische Arbeit.

In den Jahren bis zur Jahrhundertwende schrieb sie vor allem Lieder, Klavier- und viel Kammermusik, darunter Klaviertrios, von denen das erste 1886 im Rahmen eines Konzerts der Société nationale de musique in Paris uraufgeführt wurde, eine Cellosonate mit dem programmatischen Titel Titus et Bérénice, ein Streichquartett, ein Klarinettentrio, an dessen Aufführung der junge Pablo Casals beteiligt war, und ein Septett für Klavier und Streicher. Das entsprach dem Trend der Zeit, in der die in Frankreich lange vernachlässigte Kammermusik seit 1870 eine Blüte erlebte. Strohl errang damit den Respekt prominenter Kollegen wie Saint-Saëns, Fauré, d’Indy und Chausson, die sich alle selbst der Kammermusik widmeten, und ihre Werke fanden Verleger. Dennoch vollzog sie Anfang des neuen Jahrhunderts eine Wende: Sie komponierte nun überwiegend großformatige programmatische Orchester- und Vokalwerke bis hin zu Opern, die ihr Interesse an spirituellen Themen – sie wurde Theosophin – und der Natur verarbeiten.

Unvollendetes Erstlingswerk

Maurice Ravels einsätzige Sonate posthume vom April 1897 ist sein erstes Kammermusikwerk und seine erste Komposition in Sonatensatzform. Geplant hatte er eigentlich ein mehrsätziges Werk. Jahre später notierte er für den Geiger Paul Oberdoerffer den Beginn der Violinstimme mit den Worten: „Zur Erinnerung an die erste Aufführung der ersten, unvollendeten Sonate.“ Ravel und Oberdoerffer scheinen den Satz also gemeinsam musiziert zu haben, bevor er in der sprichwörtlichen Schublade verschwand und erst 1975, zu Ravels 100. Geburtstag, wieder ans Licht kam.

Das Stück entstand in einer Zeit, als der 22-Jährige Komponist sein Leben neu ausrichtete. Ravel hatte ab 1889 am Pariser Konservatorium Klavier studiert und eigentlich eine Karriere als Konzertpianist angestrebt. Doch trotz vielversprechender Anfänge und offensichtlichen Talents endete das Studium des eigenwilligen und unangepassten jungen Mannes 1895 nach wiederholten Misserfolgen bei den Abschlussprüfungen in Klavier und Harmonielehre. Zunächst setzte er seine Ausbildung privat fort. Kompositionsunterricht nahm er zu dieser Zeit noch nicht, schrieb aber 1895 erste zu Lebzeiten aufgeführte und veröffentlichte Werke wie die Habanera für zwei Klaviere, die später Teil der Rapsodie espagnole wurde. Erst 1897 erhielt er Unterricht in Kontrapunkt bei André Gédalge, von dem er sagte, er verdanke ihm „die wertvollsten Elemente“ seiner Technik, und im Januar 1898 kehrte er als Kompositionsschüler von Gabriel Fauré ans Konservatorium zurück.

Die Sonate posthume ist ausgesprochen lyrisch, dabei emotional zurückhaltend, Eigenschaften, die für Ravel charakteristisch blieben. Ihre Themen sind auf unterschiedliche Weise vom gesanglichen Charakter der Geige geprägt. Selbst die Durchführung in der Satzmitte bringt keine dramatische Zuspitzung, sondern variiert die Themen und führt sogar eine neue, wie schwerelos im hohen Register sich bewegende Melodie ein. Ravel, dessen frühes Interesse an gewagten neuen Klängen Freunden und Kommilitonen in Erinnerung blieb, experimentiert hier mit Harmonik und Klangfarben, aber auch mit dem Rhythmus: Während des zarten, hellen Dialogs, der den Satz eröffnet, wechselt permanent die Taktart. Orientierung bietet hier vor allem eine in unregelmäßigen Abständen wiederkehrende Triole. Ein zweites Thema mit mehrschichtiger Begleitung changiert zwischen Sechsachtel- und Zweivierteltakt, wohingegen das langsame dritte Thema liedhaft und rhythmisch unkompliziert ist. Dass Ravel diese beiden letzteren gegensätzlichen Themen in der Reprise kontrapunktisch übereinanderlegt, ist ebenfalls bereits typisch für sein späteres Komponieren.

Frühe Meisterschaft

Der Belgier Guillaume Lekeu war wie Ravel 22 Jahre alt, als er 1892 seine Violinsonate schrieb. Ihre umjubelte Uraufführung im folgenden März durch den belgischen Virtuosen Eugène Ysaÿe und die Pianistin Caroline Théroine schien eine große Karriere anzukündigen. Doch nur zehn Monate später war der junge Komponist tot – ein Opfer des Typhus.

Lekeu war ab 1889 Schüler von César Franck gewesen, der als Komponist und Pädagoge zu den prägenden Persönlichkeiten der französischen Musik zählte. Nach dessen Tod übernahm Vincent d’Indy Lekeus Ausbildung und ermutigte ihn, 1891 am Wettbewerb um den belgischen Prix de Rome teilzunehmen. Der Gewinn des zweiten Preises, obgleich enttäuschend, öffnete ihm nichtsdestotrotz wichtige Türen: Im Anschluss an eine Aufführung seiner Wettbewerbskantate Andromède 1892 in Brüssel bat ihn Ysaÿe um die Sonate. Er spielte dann nicht nur ihre Uraufführung, sondern dirigierte im folgenden Juni auch die Premiere von Lekeus Fantaisie sur deux airs populaires angevins.

Lekeus Sonate ist emotionaler, dramatischer und virtuoser als Ravels Erstling, enthält aber auch Momente tiefer Ruhe und Verinnerlichung, darunter der gewichtige langsame Satz. Von Franck übernahm Lekeu das Prinzip der zyklischen Form, nach dem die Sätze eines Werks miteinander zur Einheit verknüpft werden. Dazu dienen neben motivischen Verwandtschaften insbesondere drei „thèmes cycliques“, die in mehreren Sätzen erklingen, sich verändern, aber stets erkennbar bleiben, beginnend mit der zarten, versonnenen Violinmelodie des Beginns. In hoher Lage ansetzend sinkt sie wellenartig über zwei Oktaven abwärts; später präsentiert sie sich auch erregt oder leidenschaftlich, und sowohl im schnellen Hauptteil des Kopfsatzes als auch im Finale ist sie von zentraler Bedeutung. An Ende beider Sätze erscheint die Melodie in Kombination mit dem Beginn des „Vif et passionné“-Teils. Ein drittes Thema verbindet Anfangs- und Mittelsatz: Hier setzt es mit leidenschaftlicher Emphase über einem Klaviertremolo ein, dort legt es sich zart und lyrisch über die volksliedhafte Melodie des Satzzentrums.

Mitten im lebhaften, abwechslungsreichen Finale ruft Lekeu noch einmal die ruhige Stimmung des Sonatenbeginns und bald auch das zyklische Hauptthema in Erinnerung. Schließlich steuert die Musik auf eine überschwängliche, Elemente des ersten Satzes im fortissimo rekapitulierende Coda zu. Die Sonate schließt sich zum Kreis und hat sich doch völlig verändert.

Antje Reineke studierte Historische Musikwissenschaft, Rechtswissenschaft und Neuere deutsche Literatur an der Universität Hamburg und promovierte dort mit einer Arbeit über Benjamin Brittens Liederzyklen. Sie lebt als freie Autorin und Lektorin in Hamburg.

The Artists

Renaud Capuçon

Violin

Born in Chambéry, France, in 1976, Renaud Capuçon began his violin studies at the age of 14 at the Paris Conservatoire. He later completed his education with Thomas Brandis and Isaac Stern in Berlin and for three years performed as concertmaster with the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester at the invitation of Claudio Abbado. Today, he appears with many leading orchestras such as the Berliner and Wiener Philharmoniker, Boston Symphony, Orchestre de Paris, Milan’s Filarmonica della Scala, and Los Angeles Philharmonic. He has collaborated with conductors including Christoph Eschenbach, Paavo Järvi, Daniele Gatti, Andris Nelsons, François-Xavier Roth, Gustavo Dudamel, and Bernard Haitink. He is also an avid chamber musician, performing with Martha Argerich, Daniel Barenboim, Yefim Bronfman, Yuja Wang, Khatia Buniatishvili, and his brother, cellist Gautier Capuçon. Renaud Capuçon regularly appears at the festivals of Edinburgh, Lucerne, Verbier, Tanglewood, and Salzburg. He is artistic director of the Festival de Pâques in Aix-en-Provence, which he founded in 2013, the Sommets Musicaux de Gstaad, the Rencontres Musicales Evian, and, since 2021, the Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne, which he regularly leads. He has appeared as a guest conductor with the Vienna Symphony, Cologne’s Gürzenich Orchestra, and the Berliner Philharmoniker’s Karajan Academy. He teaches at the Conservatoire in Lausanne and was named a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 2016.

October 2025

Guillaume Bellom

Piano

Guillaume Bellom studied piano and violin in his native Besançon and continued his training as a pianist with Hortense Cartier-Bresson and Nicholas Angelich at the Paris Conservatoire. He is a laureate of numerous international competitions, including the Clara Haskil Competition and the Concours international de Piano in Épinal, and has received awards from the Fondation L’Or du Rhin and at the Sommets Musicaux de Gstaad. Since 2018, he has been an associate artist of the Fondation Singer-Polignac. As a soloist, he has performed with the Orchestre national de France, the Orchestre national de Montpellier, the Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne, and the Orchestre national d’Île de France, among others, and has collaborated with conductors such as Jacques Mercier, Christian Zacharias, and Marzena Diakun. Guillaume Bellom is a regular guest at the La Roque d’Anthéron Piano Festival, the Festival de Pâques in Aix-en-Provence, and the Festival des Arcs. In addition to Renaud Capuçon, his chamber music partners include Paul Meyer, Yan Levionnois, and Victor Julien-Lafferière. He has released recordings of four-hand piano works by Franz Schubert and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart together with Ismaël Margain and solo albums featuring compositions by Schubert, Haydn, Debussy, and Strauss.

October 2025