Kian Soltani Cello

Benjamin Grosvenor Piano

Program

Franz Schubert

Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in A minor D 821

Frangiz Ali-Zadeh

Habil-Sayagi for Cello und Prepared Piano

Errollyn Wallen

Dervish for Cello and Piano

César Franck

Sonata for Violin and Piani in A major

Arrangement for Cello and Piano

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in A minor D 821 (1824)

Arrangement for Cello and Piano

I. Allegro moderato

II. Adagio

III. Allegretto

Frangiz Ali-Zadeh (*1947)

Habil-Sayagi

for Cello und Prepared Piano (1979)

Intermission

Errollyn Wallen (*1958)

Dervish

for Cello and Piano (2001)

César Franck (1822–1890)

Sonata for Violin and Piani in A major (1886)

Arrangement for Cello and Piano by Jules Delsart

I. Allegretto ben moderato

II. Allegro – Quasi lento – Tempo I

III. Rezitativo-Fantasia. Ben moderato

IV. Allegretto poco mosso

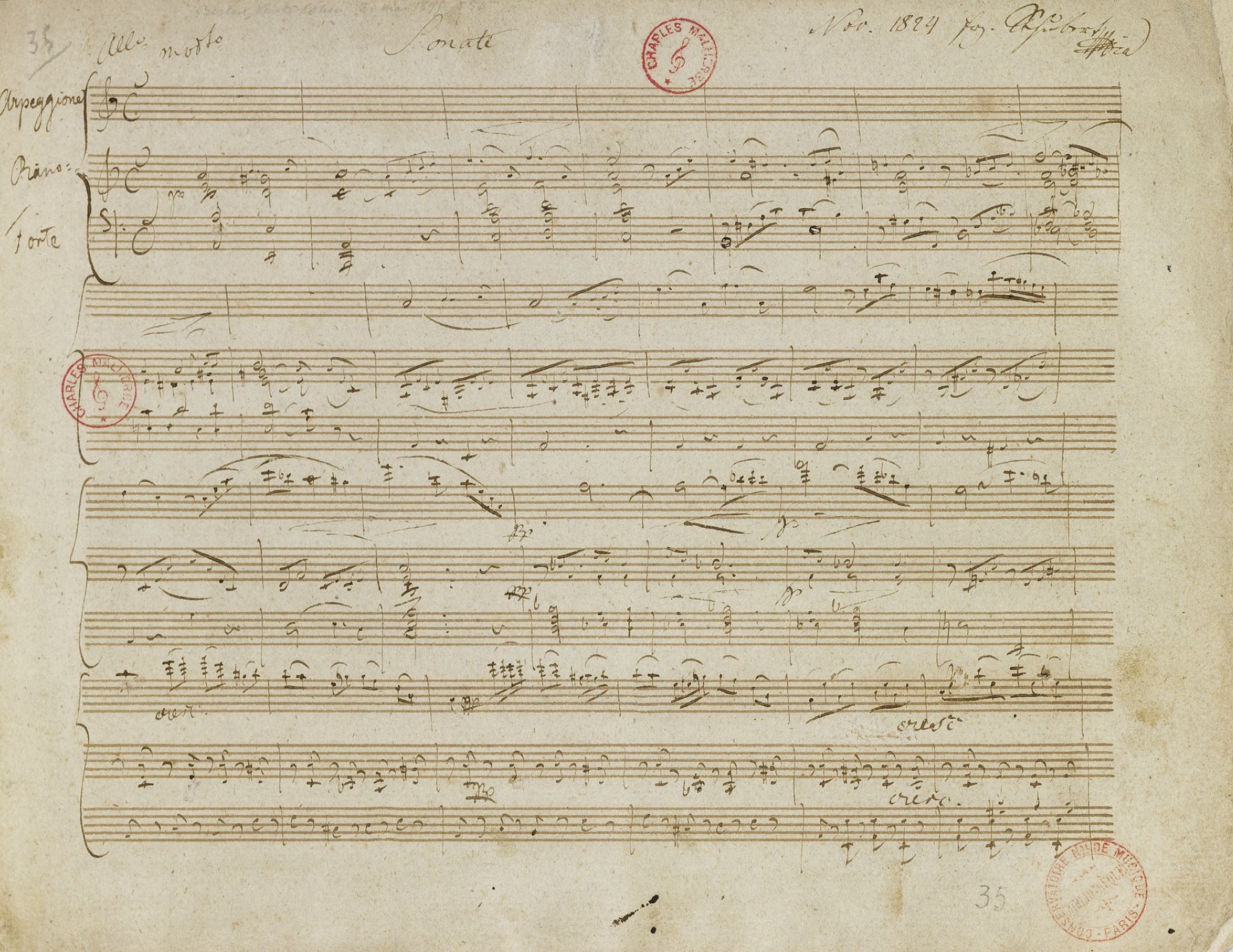

Schubert's Sonata for Arpeggione in the composer's handwriting (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Reinventions

The repertoire of major works showcasing the cello as a solo instrument—whether in a symphonic or chamber format—is limited. But this repertoire has also continually reinvented itself: witness the four works on tonight’s program, all of which can be described as transcriptions, either musical or cultural.

Program Note by Harry Haskell

Reinventions

Music for Cello and Piano

Harry Haskell

Long ago, when Yo-Yo Ma was a fresh face on the concert circuit and I was a fledgling music critic for an American newspaper, a distinguished conductor told me of his concerns about the limited repertoire available to the prodigiously gifted young cellist. “Sooner or later he’s going to run out of concertos to play,” the conductor remarked, “and what’s he going to do then?” Over the years Ma has defied such predictions, in part by continually reinventing himself. The same can be said for his instrument’s ever-expanding repertoire: witness the four works on tonight’s program, all of which can be described as transcriptions, either musical or cultural.

Divine Frivolity

Franz Schubert’s spirits were at a low ebb in the early months of 1824, despite a sustained outpouring of creativity that produced such masterpieces as the String Quartets in A minor (“Rosamunde”) and D minor (“Death and the Maiden”) and the happy-go-lucky Octet for Strings and Winds. Suffering from poor health and frequent bouts of depression, the 27-year-old composer confided morosely to his private notebook that “what I produce is due to my understanding of music and to my sorrows.” After recharging his batteries over the summer at the Esterházy family’s country estate in Hungary, he returned to Vienna in September bursting with energy and eager to continue laying the groundwork for a long-planned—and, sadly, never to be realized—“grand symphony.” A friend described him as “well and divinely frivolous, rejuvenated by delight and pain and a pleasant life.”

Composed that November for one Vincenz Schuster, the Sonata in A minor was a lighthearted detour from Schubert’s tortuous symphonic path. Schuster was the leading—indeed, almost the sole—champion of the arpeggione, a hybrid instrument recently invented by the Viennese guitar maker Johann Georg Stauffer. A cross between a cello and a guitar (one of its historic German names is Guitarre-Violoncell), the arpeggione had six strings tuned in fourths, guitar style, and a viol-like fretted fingerboard. Shaped like a bass viol, it was played with a bow and held between the player’s legs. The arpeggione enjoyed a brief vogue in the 1820s before falling into disuse, leaving Schubert’s engaging sonata (which has been arranged for cello, viola, violin, and viola d’amore) as its only enduring monument.

Although not one of Schubert’s most profound works, the A-minor Sonata has a special place in the affection of string players. (The arpeggione is one of the few obsolete instruments that the Early Music revival has left behind.) Its outgoing, uncomplicated lyricism recalls the winsome mood of the composer’s Octet. The Allegretto moderato opens with a rather melancholy tune, introduced by the two instruments in turn. The cello then bursts forth with an extraverted display featuring 16th-note arpeggios and runs in descending sequences. The middle section of the movement does not so much develop these ideas as restate and elaborate on them, with the piano playing a decidedly secondary role. The luminous E-major Adagio is notable for its rapturous, long-breathed lyricism and typically Schubertian interweaving of major and minor tonalities. It leads, by way of a short cello cadenza, to a virtuosic finale that echoes the exuberant mood, and some of the thematic material, of the first movement.

Cross-cultural Fertilizations

Azerbaijani composer Frangiz Ali-Zadeh is well known to audiences in Berlin, where she has made her second home for the past 25 years. Growing up in Soviet-era Baku, she was weaned on a diet of Shostakovich and Prokofiev and received a conventional European conservatory education. At the same time, she and her contemporaries were deeply influenced by their home country’s indigenous folk traditions. Over time Ali-Zadeh developed the highly imaginative synthesis of Eastern and Western styles and techniques that characterizes her mature concert music. Baku was a peripheral hub in the far-flung network of trade routes linking Asia and Europe, and it is no coincidence that one of the first pieces that brought Ali-Zadeh to international attention—Dervish, for a mixed ensemble of European and Azerbaijani instruments—was written in 2000 for Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble. She had already composed a Concerto for Percussion and Chamber Orchestra titled Silk Road, and further collaborations with the likes of Ma, the Kronos Quartet, and violinist Hilary Hahn have borne fruit in a cornucopia of boundary-crossing works notable for their capacious lyricism and richly varied sonorities.

Habil-Sayagi was inspired by the artistry of the late Habil Aliyev (the title means “In the Style of Habil”), a master of the long-necked Middle Eastern fiddle known as the kamancheh. Dating from 1979, it was the first of a series of works written for Russian cellist Ivan Monighetti, culminating in the cello concerto SÖVQ, which Kian Soltani—Monighetti’s protégé—premiered in Amsterdam in 2024. Ali-Zadeh says the cello is her “favorite western instrument to write for” on account of its “huge range and inexhaustible timbre possibilities.” Habil-Sayagi opens with a lugubrious, meditative preamble for the cello, to which the prepared piano belatedly adds an ominous peal of seemingly subterranean notes. As the music grows increasingly agitated and virtuosic, it takes on the character of a rhapsodic improvisation, evoking the bardic melodies, modal scales, and free-flowing rhythms associated with the traditional Azerbaijani musical genre known as mugham. Both cellist and pianist use unorthodox techniques to simulate the sounds of the kamancheh, the lute known as tar, the frame drum daf, and other folk instruments.

Like mugham, the term dervish is associated with Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam that emphasizes asceticism and personal contact with the divinity. Dervishes, as members of the Sufi brotherhood are called, cultivate a kind of spiritual ecstasy by reciting ritualistic formulas in praise of Allah and executing the hypnotically whirling dances for which they are best known to outsiders. Each of these elements—ritual, ecstasy, and gyrating movement—contributes to the spell cast by Errollyn Wallen’s brief but mesmerizing Dervish. The Belize-born composer whom Britain’s King Charles III appointed Master of the King’s Music in 2024, Wallen trained as a dancer before switching to music, and the incantatory quality of Dervish arises as much from her kinetic approach to rhythm as from the music’s subtly modulated timbres and subdued lyricism. She explains that “in dervish dances, contrary to popular myth, there is absolutely no hedonistic wildness; the swirling skirts move from rapt and still devotion. The Sufi dance is solely for worship. I wanted to capture this atmosphere (Dervish proceeds from an intense, trance-like state) and also to set it beside the passion that is in speed.”

A Romantic Spirit

The music of Belgian-born César Franck epitomizes the spirit of French Romanticism in its blend of vehemence and restraint, intense emotion and scintillating showmanship. Already acclaimed in his early 20s, Franck would emerge as a central figure of the French Romantic school. Groomed by his overbearing father for a career as a concert pianist, he spent much of his early life in pursuit of a prize that eluded him, despite his brilliance as an improviser on the keyboard. Not until his 50th year did he achieve the equivalent of a tenured position as professor of organ at the Paris Conservatoire, where he would count Debussy, Bizet, and Vierne among his pupils. Virtually all the music on which Franck’s reputation rests dates from the last dozen or so years of his life, including the ebullient Variations symphoniques for Piano and Orchestra, the Lisztian symphonic poem Le Chasseur maudit, the majestic Symphony in D minor, and the richly melodious Violin Sonata in A major.

The handful of chamber works that Franck composed at the beginning and end of his career include some of his greatest and most characteristic creations. By the time he wrote the A-major Sonata in 1886, he was firmly under the spell of Liszt and Wagner. In addition to absorbing their harmonic innovations, he adopted Liszt’s technique of generating large-scale works from a small number of germinal motifs. Franck not only dedicated his Sonata to the Belgian virtuoso Eugène Ysaÿe but presented the manuscript to the violinist as a wedding gift. The piece proved so popular that it was soon transcribed for cello, viola, and flute, becoming one of the most frequently performed works in the chamber repertoire. The Sonata figures memorably in literature as well: in John Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga, it is Irene’s playing of Franck’s “divine third movement” that triggers Young Jolyon’s fateful decision to tell his son about the tragedy that has loomed over their family since before his birth.

The A-major Sonata is deeply indebted to Ysaÿe’s purity of tone, liquid phrasing, and tasteful reticence. After hearing the violinist read through the first movement, Franck adjusted the tempo marking to a livelier Allegretto ben moderato, imparting a fresh undercurrent of urgency to the gently undulating principal theme. For all its lush chromaticism and quasi-symphonic textures, the Sonata has a chaste, limpid quality that permeates even the restless, driving intensity of the second-movement Allegro. The work lacks a true slow movement; in its place, Franck injected an oasis of repose in the form of a spacious minor-mode meditation that revisits earlier thematic material, in the manner of Liszt. Freely declamatory in style, the Recitativo–Fantasia mediates between the muscular lyricism of the first two movements and the disciplined canonic writing of the final Allegretto poco mosso.

A former performing arts editor for Yale University Press, Harry Haskell is a program annotator for Carnegie Hall in New York, the Brighton Festival in England, and other venues, and the author of several books, including The Early Music Revival: A History, winner of the 2014 Prix des Muses awarded by the Fondation Singer-Polignac.

Errollyn Wallen (© Azzurra Primavera)

Facetten eines Instruments

Das Violoncello kann in vielerlei Rollen schlüpfen – das zeigt mit vier völlig unterschiedlichen Kompositionen das heutige Programm. Neben zwei Bearbeitungen, die seit langem das Cello-Repertoire bereichern, gibt es dabei auch zwei zeitgenössische Werke zu entdecken, die virtuos die Möglichkeiten der Spieltechnik auf dem Instrument erproben.

Essay von Micheal Horst

Facetten eines Instruments

Werke für Violoncello und Klavier von Schubert, Ali-Sade, Wallen und Franck

Michael Horst

Das Violoncello kann in vielerlei Rollen schlüpfen – das zeigt mit vier völlig unterschiedlichen Kompositionen das heutige Programm. Dabei haben Kian Soltani und Benjamin Grosvenor auch zwei Bearbeitungen ausgewählt, die seit langem das Cello-Repertoire bereichern: Schuberts Arpeggione-Sonate und die A-Dur-Sonate von César Franck. Darüber hinaus gibt es die Gelegenheit, mit den Werken der aserbaidschanischen Komponistin Frangis Ali-Sade und ihrer englischen Kollegin Errollyn Wallen zwei Stücke kennenzulernen, die virtuos die Möglichkeiten zeitgenössischer Spieltechnik auf dem Instrument erproben.

„Fülle und Lieblichkeit des Tones“

Wohl nicht einmal den größten Musikfans wäre der Arpeggione heute noch ein Begriff, hätte nicht Franz Schubert dem Instrument eine Sonate zugedacht. Kurios indessen: Er scheint der einzige gewesen zu sein, der diesen – sehr missverständlichen – Namen verwendet hat, wo ansonsten die Zeitgenossen von der „Guitarre d’amour“ oder dem „Guitarre-Violoncell“ sprachen. Denn mit der Harfe (ital. arpa) hat der Arpeggione eher wenig zu tun; vielmehr handelte es sich um ein Streichinstrument mit sechs Saiten, das zwischen den Knien gehalten wurde. Nicht nur die zusätzlichen Bünde, auch die Stimmung entsprach der der Gitarre. Klanglich ging es jedoch weit über diese hinaus; in zeitgenössischen Artikeln wurde hervorgehoben, dass diese „Guitarre d’amour“ sich „an Schönheit, Fülle und Lieblichkeit des Tones in der Höhe der Hoboe, in der Tiefe dem Bassethorne sich nähert“.

Derlei Lobpreisungen konnten allerdings nicht verhindern, dass das neue Instrument, erfunden 1823 von dem Wiener Geigenbauer Johann Georg Staufer, kurze Zeit später wieder in der Versenkung verschwand. Ein gewisser Vincenz Schuster verfasste immerhin umgehend ein Lehrbuch für das Spiel auf dem Arpeggione; ihm ist auch Schuberts Komposition zu verdanken, die noch im selben Jahr 1824 zur Uraufführung kam. Veröffentlich wurde sie allerdings erst lange nach dem Tod des Komponisten im Jahr 1871, als der Arpeggione längst in Vergessenheit geraten war. Dementsprechend war der Erstausgabe bereits eine Stimme für Violoncello (alternativ auch für Violine) beigegeben, wobei allerdings einige Retuschen nötig waren, denn aufgrund der völlig anderen Quintstimmung des Cellos sind manche (vierstimmige) Akkorde darauf schlicht nicht spielbar. Die Gegebenheiten des Originalinstruments erklären auch die vielen für das Violoncello ungewöhnlich hohen Passagen, während die sonoren tiefen Lagen kaum genutzt werden. Nachbauten des Arpeggione ermöglichen es inzwischen, sich wieder einen einigermaßen authentischen Eindruck von den Vorzügen dieses instrumentalen Sonderfalls zu machen.

Kompositorisch hält sich Schubert auffällig zurück, vergleicht man die Sonate etwa mit zeitgleichen Kammermusikwerken wie dem Oktett oder den beiden Streichquartetten in a-moll und d-moll. Der Arpeggione darf sich in den Vordergrund spielen; das Klavier sekundiert auf eher zurückhaltende Art und Weise. Nichtsdestotrotz ist schon das weitgespannte erste Hauptthema von großer Eindringlichkeit, und auch in harmonischer Hinsicht wandelt der Komponist einmal mehr traumhaft sicher durch abgelegene Tonarten, um immer wieder zum anfänglichen a-moll zurückzukehren. Das fast überirdisch schwebende Adagio in leuchtendem E-Dur hält Schubert relativ kurz, um dann schnörkellos ins Finale überzuleiten. Hier kontrastiert das wienerisch angehauchte Rondo-Thema mit den alternierenden Abschnitten, in denen das Violoncello mal mit Läufen und Sprüngen jonglieren darf, dann wieder mit motorischem Elan die Musik vorantreibt, ohne dass die erforderliche Virtuosität dabei je zum bloßen Selbstzweck würde. Zwei vollgriffige Akkorde markieren das finale Ausrufezeichen – eine letzte Reminiszenz an das „Guitarre-Violoncell“.

Hommage an einen verehrten Meister

Seit vielen Jahrzehnten zählt Frangis Ali-Sade zu den Protagonistinnen der zeitgenössischen Musik, als kreative Mittlerin zwischen der Avantgarde mitteleuropäisch-amerikanischer Provenienz und der traditionsreichen Musik ihrer aserbaidschanischen Heimat. Dort gelang der 1947 geborenen Künstlerin nach ihrem kompositorischen Debüt 1970 ein rascher Aufstieg; schon 1976 hatte sie auch ihren ersten Auftritt im nicht-kommunistischen Ausland, im italienischen Pesaro. In der 1990er Jahren übersiedelte sie nach Berlin, wo sie bis heute zeitweilig lebt. Lang ist die Reihe prominenter Künstler:innen, die Ali-Sades Werke zur Uraufführung brachten – vom Kronos Quartet über die Schlagzeugerin Evelyn Glennie bis zu Mstislaw Rostropowitsch, Yo-Yo Ma und den 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker.

Aus ihrer frühen aserbaidschanischen Zeit stammt Habil-Sayagi für Violoncello und präpariertes Klavier. Das Stück speist sich aus den Wurzeln der heimatlichen Musik, verwendet aber westliche Kompositionstechniken. Es ist, das besagt schon der Titel, eine Hommage an Habil Alijew, den in Aserbaidschan hochverehrten Virtuosen auf der Kamantsche, der traditionellen Stachelfidel, deren Part hier dem Cello übertragen wird. Was scheinbar improvisiert wirkt, folgt jedoch sehr genau der Mugam-Tradition (wie die Modi der aserbaidschanischen Musik bezeichnet werden). In diesem Fall zeigt sich dies insbesondere in einer minutiös kalkulierten Steigerung der Erregungskurve – von kurzen Floskeln in tiefster Lage am Anfang („cupo, quasi niente“: düster, wie ein Nichts) über eine Passage mit wilden Doppelgriffen und eine kurze Tanz-Episode bis zu einem Arioso amoroso estatico, also einem „ekstatisch-zärtlichen Arioso“, welches das Cello in allerhöchste Lagen hinaufführt. Ali-Zade spart nicht mit griff- und spieltechnischen Herausforderungen, rasante Glissandi stehen neben imaginierter Zweistimmigkeit. Das präparierte Klavier dagegen übernimmt mit gezupften oder per Plektron angerissenen Saiten die begleitende Rolle verschiedener anderer traditioneller Instrumente wie der Langhalslaute Tar oder der Rahmentrommel Daf.

Leidenschaft und Trance

Der Ärmelkanal trennt bekanntlich das Vereinigte Königreich geographisch vom europäischen Kontinent – doch scheint er bisweilen auch die künstlerische Kommunikation zu erschweren. Anders ist es schwer zu erklären, dass eine 1958 geborene Komponistin wie Errollyn Wallen hierzulande kaum bekannt ist, während sie in Großbritannien mit ihrem vielseitigen Schaffen höchstes Ansehen und Erfolg genießt. Die in Belize geborene Musikerin schrieb Opern, Orchester- und Vokalwerke sowie unterschiedlichste Kammermusik. Gemeinsam mit der Künstlerin Sonia Boyce gestaltete sie 2022 auf der Kunst-Biennale Venedig den britischen Pavillon (der mit dem Goldenen Löwen ausgezeichnet wurde), und mit ihrem Werk Mighty River von 2017 erinnerte sie an die 200-jährige Wiederkehr der Abschaffung der Sklaverei in England. Wallen erhielt Kompositionsaufträge zum Goldenen und Diamantenen Thronjubiläum von Queen Elizabeth und wurde im August vergangenen Jahres von Charles III. zum „Master of the King’s Music“ ernannt.

Schon 2001 entstand die kurze Duo-Komposition Dervish für Violoncello und Klavier. Die Komponistin selbst stellte dazu klar: „In den Derwisch-Tänzen gibt es entgegen dem populären Mythos absolut keine hedonistische Wildheit; die wirbelnden Röcke bewegen sich zwischen Verzückung und stiller Hingabe. Der Sufi-Tanz dient ausschließlich der Anbetung. Ich wollte diese Atmosphäre (Dervish geht von einem intensiven, tranceartigen Zustand aus) einfangen und sie auch neben die Leidenschaft stellen, die in der Geschwindigkeit steckt.“ Wallen baut ihre Kompositionen aus kurzen Abschnitten auf, die in der Tat fast trance-artig wiederholt werden und sich aus ätherischen Höhen kommend allmählich immer mehr erden. Klopfeffekte suggerieren ein zusätzliches Rhythmusinstrument. Auf dem Höhepunkt bricht die Musik ab, um nach einer Pause noch einmal das Motiv des Anfangs aufzunehmen.

Spätromantische Klangpalette

Für den belgischen Komponisten César Franck war das letzte Jahrzehnt vor seinem Tod 1890 in Paris von späten Erfolgen gekrönt. Nach dem Ende des Deutsch-Französischen Krieges 1871 standen die Zeichen auf einem musikalischen Neustart à la française, und Franck gelang es, sich mit wegweisenden Kompositionen gegenüber Kollegen wie Camille Saint-Saens und Gabriel Fauré zu profilieren. Erfolgreichstes Werk – vor dem Klavierquintett und dem Streichquartett – war dabei von Anfang an die Violinsonate A-Dur, die als Hochzeitsgeschenk für den aufstrebenden Geiger (und belgischen Landsmann) Eugène Isaÿe entstand. Nach der Brüsseler Uraufführung 1886 feierte das Werk im Jahr darauf auch in Paris einen viel beachteten Erfolg – mit der Folge, dass ein mit Franck befreundeter Cellist, Jules Densart, sich mit Einverständnis des Komponisten sogleich an die Ausarbeitung einer Fassung für Violoncello machte. Dabei ging es fast ausschließlich um die Transposition der Violinstimme in eine tiefere Lage; der Klavierpart blieb hingegen unangetastet.

Nachdem sich der Vorhang mit einem suggestiven Dominant-Nonen-Akkord im Klavier geöffnet hat, stellt die Violine mit einer Phrase aus auf- und absteigenden Terzen das Motiv vor, das Franck in immer wieder neuen Verwandlungen zum zentralen gestalterischen Element der Sonate macht. Die kontrapunktischen Verflechtungen werden dabei mit einer Souveränität behandelt, wie sie wohl besonders einem Orgelspezialisten wie Franck zur Verfügung stand. Von großer Raffinesse sind auch die harmonischen Experimente, in denen der Komponist die ganze spätromantische Palette zum Einsatz bringt, indem er die chromatischen Wanderungen durch die Tonarten auf kleinste Räume fokussiert und damit eine enorme Binnenspannung innerhalb der Musik schafft.

Vieles in der formalen Disposition dieser Sonate sticht aus den Konventionen der Zeit heraus, nicht zuletzt der mit „Recitativo – Fantasia“ überschriebene dritte Satz: Franck lässt ihn im Stil einer großen Soloszene für die Violine beginnen, um dann nach und nach beide Instrumente in Dialog treten und sie quasi in eine Arie übergehen zu lassen, welche wiederum der Violine, von sanften Triolen im Klavier begleitet, breiten Raum für ausdrucksvolle Kantilenen bietet. Ein wirkliches Unikat stellt das Finale dar, in dem Franck seine kontrapunktischen Fähigkeiten in einem veritablen Kanon vorführt, wobei wuchtige Klavierbässe eine zusätzliche Orgelstimme simulieren. Im Mittelteil greift der Komponist noch einmal ausführlich auf den ariosen Teil des vorangegangenen Satzes zurück, doch das Kanon-Thema hat das letzte Wort: Mit kompakten Akkorden – man fühlt sich an das „volle Werk“ einer großen Orgel erinnert – kommt die Sonate zu einem gloriosen Abschluss.

Der Berliner Musikjournalist Michael Horst arbeitet als Autor und Kritiker für Zeitungen, Radio und Fachmagazine. Außerdem gibt er Konzerteinführungen. Er publizierte Opernführer über Puccinis Tosca und Turandot und übersetzte Bücher von Riccardo Muti und Riccardo Chailly aus dem Italienischen.

The Artists

Kian Soltani

Cello

Born in Bregenz, Austria, to a Persian family of musicians, Kian Soltani began his cello studies at the age of 12 with Ivan Monighetti at the Music Academy in Basel and completed his education at the Kronberg Academy with Frans Helmerson. A recipient of a scholarship from the Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation, he won first prize at the 2013 International Paulo Cello Competition and has been in demand internationally as a soloist and chamber musician ever since. He has appeared with Zurich’s Tonhalle Orchestra, the Berlin Staatskapelle, the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Cologne’s WDR Symphony, and the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia as well as at the festivals in Salzburg, Verbier, Lucerne, Rheingau, and at the BBC Proms. This season, he performs with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and makes debuts with the Orchestra National de France and the Sydney Symphony, among others. Closely associated with the Pierre Boulez Saal since its inception, his performances here have included Beethoven’s complete piano trios with Michael and Daniel Barenboim, which were released as a live recording, His discography also includes works for cello and piano by Schubert, Schumann, and Persian composer Reza Vali, piano trios by Dvořák and Tchaikovsky with Lahav Shani and Renaud Capuçon, as well as Dvořák’s Cello Concerto, together with Maestro Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin. He won a 2022 Opus Klassik award for his solo album Cello Unlimited. Kian Soltani plays the “London, ex Boccherini” Stradivari, kindly loaned to him by a generous sponsor through the Beares International Violin Society.

November 2025

Benjamin Grosvenor

Piano

In demand internationally as a soloist, British pianist Benjamin Grosvenor has performed with all major London orchestras as well as the Cleveland, Chicago, and Boston symphony orchestras, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Berlin’s Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester, the Orchestre National de France, and the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, among others. Solo recitals have taken him to Tokyo, Warsaw, the Barbican and Southbank Centre in London, Wigmore Hall, Klavierfestival Ruhr, Festival de La Roque d'Anthéron, and the BBC Proms on several occasions. Highlights this season include performances with the Philharmonia Orchestra, the Filarmonica della Scala, the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, and his debut with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, as well as recitals at Carnegie Hall, in Chicago, Amsterdam, Singapore, Melbourne, and London. With Kian Soltani, violinist Hyeyoon Park, and violist Timothy Ridout, he will perform at the Vienna Musikverein and the Heidelberger Frühling festival.

November 2025