Elena Bashkirova

Piano and Artistic Direction

Emmanuel Pahud Flute

Michael Barenboim Violin

Madeleine Carruzzo Violin

Mohamed Hiber Violin

Yulia Deyneka Viola

Adrien La Marca Viola

Ivan Karizna Cello

Alexander Kovalev Cello

Astrig Siranossian Cello

Program

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Flute Quartet No. 1 in D major K. 285

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

String Quartet in D major Op. 44 No. 1

Fanny Hensel

Warum sind denn die Rosen so blass Op. 1 No. 3

Im Herbste Op. 10 No. 4

Vorwurf Op. 10 No. 2

Du bist die Ruh Op. 7 No. 4

Abendbild Op. 10 No. 3

Arrangements for Flute and Piano

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

String Sextet in D major Op. 10

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Flute Quartet No. 1 in D major K. 285 (1777)

I. Allegro

II. Adagio

III. Rondeau

Emmanuel Pahud Flute

Mohamed Hiber Violin

Adrien La Marca Viola

Astrig Siranossian Cello

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847)

String Quartet in D major Op. 44 No. 1 (1838)

I. Molto allegro vivace

II. Menuetto. Un poco allegretto

III. Andante espressivo con moto

IV. Presto con brio

Albena Danailova Violin

Madeleine Carruzzo Violin

Yulia Deyneka Viola

Ivan Karizna Cello

Intermission

Fanny Hensel (1805–1847)

Warum sind denn die Rosen so blass Op. 1 No. 3

Im Herbste Op. 10 No. 4

Vorwurf Op. 10 No. 2

Du bist die Ruh Op. 7 No. 4

Abendbild Op. 10 No. 3

Arrangements for Flute and Piano

Emmanuel Pahud Flute

Elena Bashkirova Piano

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957)

String Sextet in D major Op. 10 (1914–6)

I. Moderato – Allegro

II. Adagio. Langsam

III. Intermezzo. In gemäßigtem Zeitmaß, mit Grazie

IV. Finale. So rasch als möglich – Doppelt so langsam – Tempo I

Michael Barenboim, Mohamed Hiber Violin

Adrien La Marca, Yulia Deyneka Viola

Astrig Siranossian, Alexander Kovalev Cello

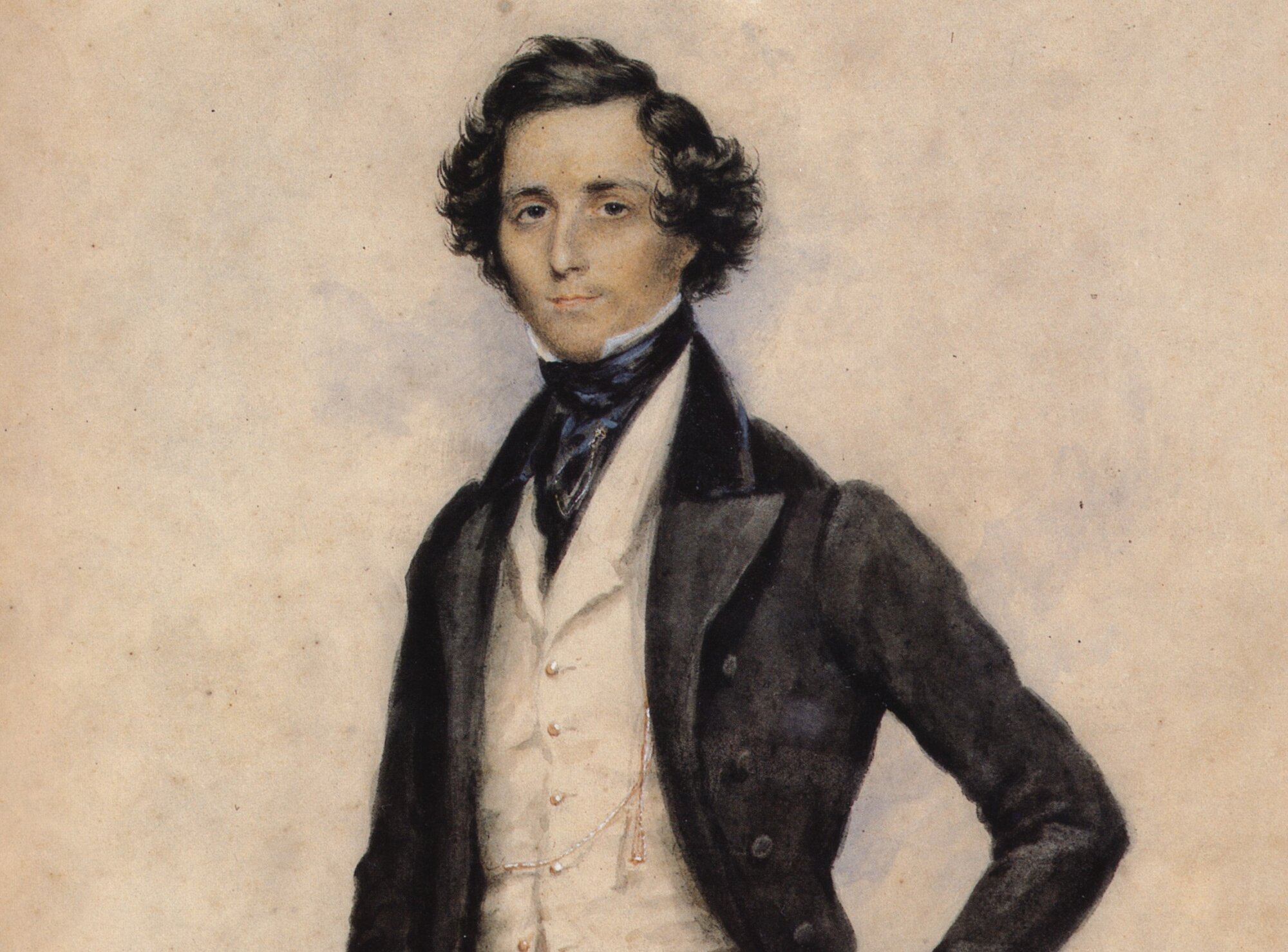

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, portrait by James Warren Childe (1830, detail)

Peerless Prodigies

For the third edition of the Pierre Boulez Saal’s biennial Mendelssohn Festival, curator and artistic director Elena Bashkirova focuses on four composers who displayed prodigious musical talent virtually from infancy: while Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was paraded around the courts of Europe as a wunderkind, Felix Mendelssohn's family shielded him from wider adulation. His older sister Fanny, though barely less gifted, was a victim of contemporary social attitudes. Moving to the early 20th century, Erich Wolfgang Korngold was dubbed “the little Mozart” at the age of five and vigorously promoted in Vienna by his domineering father.

Essay by Richard Wigmore

Peerless Prodigies

Chamber Music by Mozart, Mendelssohn, Hensel, and Korngold

Richard Wigmore

For the third edition of the Pierre Boulez Saal’s biennial Mendelssohn Festival, curator and artistic director Elena Bashkirova focuses on four composers who displayed prodigious musical talent virtually from infancy. The most famous child prodigy of them all, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was paraded around the courts of Europe as a wunderkind. In contrast, Felix Mendelssohn was carefully shielded from wider adulation by his affluent family in Berlin. His older sister Fanny, though barely less gifted, was a victim of contemporary social attitudes. Moving to the early 20th century, Erich Wolfgang Korngold was dubbed “the little Mozart” at the age of five and vigorously promoted in Vienna by his domineering father Julius, the city’s most influential music critic.

For Amateurs and Connoisseurs: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

By 1777 Mozart had experienced both triumph and frustration on his European travels, while his native Salzburg had come to seem a place of servitude. That autumn the 21-year-old composer set out with his mother on a 15-month trip to Mannheim and Paris. The journey would bring professional disappointment, and personal tragedy in the death of his mother, but Mozart’s initial mood was buoyant. In Mannheim he found diversion with his first love, the soprano Aloysia Weber, and received a potentially lucrative commission from an amateur flutist, Ferdinand Dejean, known to him as “the Indian Dutchman,” for “three easy little concertos and a pair of quartets.” (Dejean was in fact a German surgeon who had worked for the Dutch East India Company.)

Mozart made slow progress with the commission, partly because, as he wrote to his father Leopold, “I become quite powerless whenever I have to write for an instrument I cannot bear.” In the event he completed only two concertos, one of them adapted from his Oboe Concerto, plus the two commissioned quartets for flute and string trio. The affair did not end happily. Dejean kept Mozart waiting for his fee, and when it did eventually arrive it was only half of the agreed amount, much to the composer’s chagrin.

Despite Mozart’s professed dislike of the flute, he was far too much of a pro to let his standards slip; and his concertos and quartets for the instrument are all elegantly crafted works in his most mellifluous galant vein. Completed in Mannheim on Christmas Day 1777, the Flute Quartet in D major K. 285 begins with a frolicking Allegro that gave Dejean plenty of scope to display his nimble technique. The jewel of the quartet is the B-minor Adagio, music of pure rococo enchantment in which the flute spins its delicately plaintive song above hushed pizzicato strings. This leads without a break into the ebullient rondo finale. More than in the first movement, flute and strings here work in close collusion, not least in the second episode, where the viola and flute spar in canonic imitation.

Mozart finally, and acrimoniously, departed the service of the Salzburg Prince-Archbishop Colloredo in June 1781. While Leopold was aghast, for the next few years, at least, his decision was triumphantly vindicated. He secured a growing income from concerts, publishers’ fees, and teaching the daughters of the Viennese nobility. As he proudly informed his father, he commanded top fees for his keyboard lessons, strictly non-refundable in the event of cancellation.

During his most lucrative years, 1783–6, Mozart promoted himself as composer-virtuoso in the magnificent series of piano concertos he premiered at his own subscription concerts, held in the Mehlgrube (a restaurant-cum-concert hall) or the Imperial Burgtheater during Lent and Advent. There were six concertos in 1784 alone. Appealing both to “amateurs” (“Liebhaber”) and “connoisseurs” (“Kenner”), these masterpieces represent a unique amalgam of virtuoso display, symphonic organization, and chamber-music refinement. Dated February 9, the first of the 1784 works, the Piano Concerto in E-flat major K. 449, was initially intended for a gifted pupil, Barbara (“Babette”) Ployer, but certainly performed by Mozart himself as well. In a letter to Leopold he noted that it was “a concerto of quite a special kind, composed rather for a small orchestra than a large one.” Indeed, to ensure wider sales Mozart specified that the oboes and horns could be omitted, and the concerto performed a quattro, either with multiple or, as here, solo strings.

More concise than Mozart’s other mature concertos, K. 449 has a richness and subtlety of string writing that suggest the influence of the contemporary string quartets dedicated to Haydn. The Concerto also reminds us that so much of Mozart’s instrumental music is opera by other means. The restless tone of the first movement, in triple time, is set by the ambiguous opening (we initially seem to be in C minor), with only the suave second theme providing an oasis of stability. Chromatic harmony also lends a disquieting undercurrent to the ostensibly serene Andantino. Like so many Mozart concerto slow movements, this is a soulful soprano aria reimagined in pianistic terms. The finale is a rondo of irresistible energy and panache, propelled by a strutting theme that is ingeniously varied each time it reappears. Mozart here deftly combines the “learned” style (calculated to appeal to “Kenner” in his Viennese audience) with the comic, conspiratorial spirit of opera buffa.

“I Like It Very Much, I Hope You Will Too”: Felix Mendelssohn

While the happily named Felix Mendelssohn was sheltered from international celebrity as a boy, by the age of 12 he was dazzling friends and family in Berlin with works in virtually every genre, from keyboard and chamber music to symphonies and operas. In 1819, aged ten, he had begun studies with the venerable Carl Friedrich Zelter, whose musical gods were Bach, Haydn, and Mozart. Zelter ensured that these masters were the models for the numerous instrumental works Mendelssohn composed under his tutelage.

Dating from 1820, the Violin Sonata in F major remained in manuscript during Mendelssohn’s lifetime and only came to light in the 1970s. We can sense Mozart’s spirit in the graceful violin-piano exchanges that open the first movement, though the obsessive concentration on the initial fanfare motif is more typical of Haydn. The second and third movements are overtly Haydnesque: the Andante consists of variations on two alternating themes, one in F minor, the other in F major—a favorite form of Haydn’s—while the final Presto is a skittering moto perpetuo that distantly recalls the finale of Haydn’s “Lark” Quartet.

By now a fully fledged master, Mendelssohn composed two superb string quartets, Op. 13 in A major and Op. 12 in E-flat major, in 1827 and 1829. A decade later, newly married, he returned to the quartet medium with the Op. 44 trilogy, written for the string quartet led by his friend Ferdinand David, concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Although published at the head of the Op. 44 set, the D-major Quartet was the last of the three to be composed. It was Mendelssohn’s own favorite. After completing it in July 1838 he wrote euphorically to David: “I like it very much. I hope you will too. I rather think you will, since it is more spirited and, I think, likely to be more grateful to the players than the others.”

Exploiting the natural resonance of strings in the key of D major, Op. 44 No. 1 is indeed “grateful” for all four players. It is also the most uninhibitedly extrovert of all Mendelssohn’s quartets. The opening Molto allegro vivace and the hurtling saltarello finale give plenty of scope to David’s virtuosity. More than once the music threatens to turn into a violin concerto, though the animation of the first movement is momentarily stilled by a hushed theme in F-sharp minor. Both inner movements are Mendelssohnian jewels. The minuet, like that in the “Italian” Symphony, looks nostalgically back to the 18th century, while the trio evokes a pastoral musette. Even more enchanting is the B-minor Andante espressivo. With a nod, perhaps, to the Allegretto scherzando of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 8 (a work Mendelssohn often conducted), this music combines a relaxed pace with filigree scherzando textures. The mood, though, is reflective, even wistful, enhanced by poignant shafts of viola color.

After Goethe heard the 12-year-old Mendelssohn play in Weimar in 1821, the poet-sage remarked that the boy prodigy possessed “the smallest modicum possible of the phlegmatic, and the maximum of the opposite quality.” This nervous vitality is a crucial feature of the music as well as the man, not least in the glorious Piano Trio in D minor Op. 49, composed in the summer of 1839. Mendelssohn played a draft of the Trio to the composer-conductor Ferdinand Hiller, who persuaded him to revise the piano part in a more up-to-date style. The keyboard writing in the first movement, especially, has a concerto-like brilliance, though Mendelssohn was careful to ensure a true democracy between the three instruments, as Robert Schumann approvingly noted in an enthusiastic review of the piece.

Opening with a plangent cello cantabile over unquiet keyboard syncopations, the first movement mingles agitation, grace, and pathos. As so often in his sonata-form movements, Mendelssohn contrives a magical transition from the development to the recapitulation. After the second theme—as melodically alluring as the first—has subsided in a mysterious lull, the opening theme reenters pianissimo with a seraphic descant on the violin: one of the most haunting moments in all of Mendelssohn’s chamber music. The Andante, in B-flat major, is a Song without Words whose tenderness is ruffled by a plaintive episode in the minor key. This is followed by one of those irresistible “fairy” scherzos that Mendelssohn made his own, delighting in irregular phrases and quicksilver repartee between the three players. Marked “leggiero e vivace,” this is music perfectly fashioned to display Mendelssohn’s famed finger staccato and “rapidity of execution.”

Back in D minor, the rondo finale opens with a quiet, tense main theme whose nagging dactylic rhythms give it a faintly Schubertian flavor. The second episode introduces a soaring cello melody that flowers into a cello-violin duet. This new theme then reappears towards the end of the movement, piloting the music to D major for a triumphant ending.

More than a Gift for Melody: Fanny Hensel

Four years older than Felix, Fanny Mendelssohn was comparably precocious as a composer and pianist. Like her brother, she received composition lessons from Carl Friedrich Zelter. But while her father and, especially, her brother acknowledged her talent, they deemed it “immodest” for a woman to publish music. Felix did, though, publish six of her songs surreptitiously as part of his own Op. 8 and Op. 9 in 1828 and 1830, respectively. In adulthood, Fanny Hensel, as she became after her marriage in 1829 to the painter Wilhelm Hensel, was famed both for her musical gifts and her formidable intellect. She evidently never sought to charm. Visiting her home in 1842, the English composer William Sterndale Bennett recalled, with more than a touch of misogyny, that he was “never so frightened to play to anyone before, and to think that this terrible person should be a lady. However, she would frighten many people with her cleverness.”

Fanny’s prolific output includes nearly 300 songs, the best of which easily rival those of her brother. Her self-confidence as a composer grew after her marriage. Before a group of her songs, including the melancholy Warum sind denn die Rosen so blass, appeared as her Op. 1 in 1846 she wrote to Felix: “I hope I won’t disgrace all of you through my publishing.” The songs were an immediate success. In May of the following year Fanny collapsed and died, aged just 41, while conducting a rehearsal of her brother’s cantata Die erste Walpurgisnacht. Within six months he too would be dead. Performed in arrangements for flute and piano, Fanny’s songs reveal her gift for shapely, expressive melody and apt accompaniment. Abendbild and Du bist die Ruh, to a Rückert poem made famous by Schubert, are in her most idyllic vein. In contrast, the textures of both Im Herbste and the troubled Vorwurf suggest the influence of Bach’s chorale preludes that had formed part of Fanny’s early musical education.

An Unmistakable Signature: Erich Wolfgang Korngold

“I never wanted to compose. I only did it to please my father,” remarked Erich Wolfgang Korngold, the latest of the prodigies in this weekend’s program. Reluctant or otherwise, the young Erich Wolfgang, supported by the ambitious Julius, was in the Mozart-Mendelssohn league as a musical prodigy. In adulthood he would rival Richard Strauss as a composer of successful operas (Die tote Stadt, Das Wunder der Heliane) and instrumental music. After his works were condemned as entartet—“degenerate”—by the Nazis, he escaped to the United States to reinvent himself, like his contemporary Kurt Weill, as a composer for Broadway and Hollywood.

The teenaged Korngold had already made his reputation in Vienna when he began work on his String Sextet in D major Op. 10 in 1914. Completed in 1916, it was premiered by the celebrated Rosé Quartet and friends in May 1917 in a concert of contemporary chamber music. The response from both press and public was enthusiastic. “From the very first bar Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s signature is unmistakable,” ran one review. “Of composers alive today, apart from Strauss there can be no one who writes so personally as he.” Although influenced by the Brahms sextets and Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, Korngold’s Sextet does indeed have a distinct flavor of its own. After its spiky staccato opening for second viola, the first movement, in sonata form, veers between lyrical warmth and chromatic anguish. With constant changes of key, tempo, and meter, nothing ever seems quite settled. Even the luscious second theme unfolds against ghostly sul ponticello sonorities in the violas. For the Adagio Korngold drew on an unpublished song and from it created a movement of mounting intensity that rises to a feverish climax before finally subsiding in an unearthly glow.

If the hothouse chromaticism of the Adagio owes something to Verklärte Nacht, the third movement is a quintessentially Viennese waltz-intermezzo that evokes both Brahms and Mahler without sounding like either. As early reviewers noted, the music’s nostalgic charm—to which we might add quirky playfulness—made an instant appeal to audiences. The Presto finale lives up to its marking “with fire and humor.” This is music of unquenchable good humor, with a country dance vein to its themes and a pervasive spirit of comic banter. Midway through the movement the tempo broadens for a cello-led meditation on the first movement’s main theme—the Sextet’s expressive climax—before sentiment is finally banished in a madcap sendoff.

Born, like Korngold, into a cultured Viennese Jewish family, the pianist Paul Wittgenstein (older brother of the philosopher Ludwig) lost his right arm in combat early in World War I. Undaunted, he developed a virtuoso technique for left hand alone, mastering difficulties that would have challenged any two-handed pianist. Wittgenstein, who later also fled Austria for the United States, inspired works from composers including Ravel, Prokofiev, Britten, and Strauss. Korngold wrote two works for him: first a concerto, then, in 1930, a five-movement Suite for Piano Left Hand, Two Violins, and Cello Op. 23.

The term “suite” immediately conjures Baroque associations. And in each of the movements Korngold evokes the Austro-German musical past. Opening with a torrential solo cadenza designed to Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1919 showcase Wittgenstein’s virtuosity, the Prelude and Fugue refract Johann Sebastian Bach through a (very) late-Romantic prism. Moving forward a century and a half, Korngold’s second movement deconstructs that quintessentially Viennese genre, the waltz, in an idiom that veers between Johann Strauss, Brahms, and Schoenberg. Titled “Groteske,” the Suite’s centerpiece puts an ironic spin on the traditional scherzo and trio. With their driving motor rhythms and whiff of the circus, the outer sections are mordantly modernist, while the nostalgic trio seems to reflect the spirit of Brahms. The slow movement (“Lied”) draws on a yearning love song, Was du mir bist (“What are you to me”), from Korngold’s recent Op. 22 set. This is the composer at his most uninhibitedly Romantic. Again invoking the Viennese musical past, the finale interleaves variations on a gently musing theme (announced by the cello) with livelier episodes. Towards the end Korngold takes the slow movement’s song melody and turns it into a lusty dance: a deft, Brahmsian touch of thematic transformation that sets the seal on a thoroughly delightful tour through Austro-German musical history.

Richard Wigmore is a writer, broadcaster, and lecturer specializing in Classical and Romantic chamber music and lieder. He writes for Gramophone, BBC Music Magazine, and other journals, and has taught at Birkbeck College, the Royal Academy of Music, and the Guildhall. His publications include Schubert: The Complete Song Texts and The Faber Pocket Guide to Haydn.

Fanny Hensel, née Mendelssohn, portrayed by her husband Wilhelm Hensel (1847)

Das Wunder der Inspiration

Der Begriff des Wunderkindes ist nicht unproblematisch – doch in Bezug auf die vier Komponist:innen, die im Mittelpunkt des diesjährigen Mendelssohn-Festivals im Pierre Boulez Saal stehen, ist er zweifellos treffend. Sie alle waren keine beifallumrauschten Kometen, die allzu schnell wieder verglühten, sondern einzigartige künstlerische Talente, deren Entwicklung von den Eltern sorgfältig begleitet und gefördert wurde, sei es aus ideellen, finanziellen oder sozialen Motiven.

Werkeinführung von Michael Horst

Das Wunder der Inspiration

Kammermusik von Mozart, Mendelssohn, Hensel und Korngold

Michael Horst

Der Begriff des Wunderkindes ist nicht unproblematisch – doch in Bezug auf die vier Komponist:innen, die im Mittelpunkt des diesjährigen Mendelssohn-Festivals im Pierre Boulez Saal stehen, ist er zweifellos treffend. Sie alle waren keine beifallumrauschten Kometen, die allzu schnell wieder verglühten, sondern einzigartige künstlerische Talente, deren Entwicklung von den Eltern sorgfältig begleitet und gefördert wurde, sei es aus ideellen, finanziellen oder sozialen Motiven. Leopold Mozart erkannte die Begabung seines Sohnes sehr früh und präsentierte ihn, gemeinsam mit der ebenso talentierten Schwester Nannerl, der Öffentlichkeit in halb Europa, ohne darüber die gründliche musikalische Ausbildung der Kinder zu vernachlässigen. Die Berliner Bankiersfamilie Mendelssohn ermöglichte den Kindern Felix und Fanny – wie ihren beiden jüngeren Geschwistern – die bestmögliche Erziehung durch Privatlehrer, wobei neben der Musik auch Sprachen, Literatur und Mathematik selbstverständlich dazugehörten. Ein knappes Jahrhundert später schließlich genoss auch Erich Wolfgang Korngold in Wien eine Ausbildung, die seine von Gustav Mahler und Richard Strauss bewunderte Begabung in die Hände der besten Lehrer legte.

„...ein Concert von ganz besonderer Art“: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Die beiden Werke Mozarts, die an diesem Wochenende zu hören sind, stammen aus einer Zeit, als die Ausbildung seiner frühen Jahre längst Früchte getragen hatte. Das Klavierkonzert Es-Dur KV 449 ist sozusagen ein Nachzügler zu jenen drei Klavierkonzerten (KV 413–415), die im Winter 1782/83 entstanden, als der Komponist nach seiner Übersiedlung nach Wien ein neues Publikum zu gewinnen versuchte. Dabei setzte er explizit auf das häusliche Musizieren, also – wie es im Vorwort zu diesen Konzerten heißt – auf die Möglichkeit, sie „auch nur a quattro, nämlich mit 2 Violinen, 1 Viole, und Violoncello aufzuführen“. Im selben Winter begonnen, wurde das Es-Dur-Konzert allerdings erst im Frühjahr 1784 vollendet. Inzwischen war die 19-jährige Barbara Ployer (genannt Babette) Mozarts Klavierschülerin geworden, und sie brachte das Werk im Wiener Haus ihres musikliebenden Onkels zur Uraufführung. Mit einem Eintrag dieser Komposition begann Mozart sein „Verzeichnüß aller meiner Werke“, das er bis zum Lebensende führen sollte. An den Vater schrieb er: „Das ist ein Concert von ganz besonderer Art, und mehr für ein kleines, als großes Orchester geschrieben.“

Für die Bläserstimmen sind nur Oboen und Hörner vorgesehen, die in der (ebenfalls vom Komponisten selbst stammenden) Quintettversion problemlos wegfallen können, da sie eher als musikalische Farbe eingesetzt werden und keine motivisch eigenständige Rolle spielen. Im ersten Satz stellt Mozart dem energischen Hauptthema in der festlichen Tonart Es-Dur einen lieblichen Seitengedanken gegenüber. Zwischen diesen beiden Polen entfaltet der Solopart, unterstützt von den Streichern, ein abwechslungsreiches Spiel der Stimmungen. Der langsame Satz mit seinem fein ziselierten melodischen Geflecht, dem auch die melancholischen Töne nicht fehlen, weist bereits den Weg zu den großen Klavierkonzerten der späteren Jahre. Von ungetrübter Energie ist das Finale, in dem das merkwürdig barock anmutende Thema mit immer neuen Variationen umspielt wird. Kontrapunktische Einschübe kontrastieren mit Momenten im Stil der Opera buffa; eine quirlige Coda im Sechsachteltaakt beschließt das Werk.

Zurück zum Jahresende 1777, als Mozart einige Monate in Mannheim verbrachte, führt das Flötenquartett D-Dur KV 285. Statt der erhofften Stelle am Hof des musikbegeisterten Kurfürsten Karl Theodor von der Pfalz ergatterte der 21-Jährige dort allerdings nur einige Aufträge – darunter für mehrere Flötenquartette, die er für Ferdinand Dejean komponierte, einen begabten Amateurmusiker und Mediziner, der viele Jahre als Schiffsarzt im Dienst der Niederländischen Ostindien-Kompanie unterwegs gewesen war. Am 18. Dezember 1777 konnte Mozart an den Vater vermelden: „Ein quartetto für den indianischen holländer, für den wahren Menschenfreund ist auch schon bald fertig.“

Aus dem Kontext der Flötenquartette stammt jene vielzitierte Bemerkung Mozarts, dass er für ein Instrument schreiben müsse, „das ich nicht leiden kann“ und deshalb mehr Zeit als sonst benötige. Wie ernst diese Rechtfertigung gegenüber Vater Leopold zu nehmen ist, bleibt offen. In jedem Fall sprüht das D-Dur-Quartett vor Spielfreude, und vor allem im ersten Satz lässt Mozart immer wieder solistische Passagen der Flöte mit kammermusikalischem Miteinander aller Stimmen abwechseln. Das Adagio ist wie eine Serenade angelegt: Mit einer ausdrucksvollen Melodie schwebt die Flöte über der Pizzicato-Begleitung der Streicher. Das Rondo wiederum, nahtlos an das Adagio anschließend, kombiniert quicklebendig den eingängigen Refrain mit drei abwechslungsreichen Couplets.

Ein „Mozart des 19. Jahrhunderts“: Felix Mendelssohn

Elf Jahre alt war Felix Mendelssohn, als er 1820 seine Violinsonate F-Dur zu Papier brachte. Ein Jahr zuvor hatte der Kompositionsunterricht bei Carl Friedrich Zelter, dem Leiter der Berliner Singakademie und Goethe-Freund, begonnen, der seinen Schützling vor allem Kontrapunkt, Choral und Kanon studieren ließ. Seine musikalischen Leitsterne waren Bach, Mozart und Haydn (und mit Einschränkung Beethoven); die zeitgenössischen, frühromantischen Klänge eines Hummel oder Weber – dessen Freischütz ein Jahr später im Schauspielhaus am Gendarmenmarkt uraufgeführt werden sollte – riefen eher Naserümpfen hervor.

Fast hat man den Eindruck, als habe der junge Felix die zahllosen Kontrapunkt-Exerzitien durch eine enorme Zahl „echter“ Kompositionen ausgleichen wollen. Die Werke sprudelten nur so aus ihm heraus: Klavier- und Orgelstücke, Solo- und Chorlieder, kleine dramatische Szenen und immer wieder Fugen. Anders als der junge Mozart, der auf seinen Reisen früh mit italienischer Oper und französischer Orchestermusik in Kontakt kam und die Londoner Symphonien Johann Christian Bachs kennengelernt hatte, übte sich Felix im konservativen Stil des Berliner Musiklebens. Das zeigen die traditionellen Bassfiguren des Klavierparts im ersten Satz der Violinsonate ebenso wie dessen klare formale Gliederung, in der kanonische Einsprengsel nicht fehlen dürfen. Doch schon im folgenden Variationensatz schlägt er einen individuellen Tonfall an, der abwechslungsreich zwischen dunklem f-moll und hellem F-Dur changiert. Das Presto- Finale ähnelt dem Allegro: vertraute musikalische Formeln werden mit kontrapunktischen Elementen verknüpft, aber auch mit einem erstaunlich sicheren Gespür für musikalische Struktur in rasantem Tempo vorgeführt.

Zur Zeit der Entstehung des Klaviertrios d-moll op. 49 war Felix Mendelssohn zu einer europäischen Berühmtheit geworden, gefeiert vor allem in England und unermüdlich unterwegs als Pianist, Komponist und Dirigent. 1837 hatte er in Frankfurt die kunstbegeisterte Cécile Jeanrenaud, Tochter eines hugenottischen Predigers, geheiratet, knapp ein Jahr später wurde der erste Sohn Carl (nach Zelter) Wolfgang (nach Goethe) Paul geboren. Im glücklichen Sommer 1839, den er bei Céciles Familie in Frankfurt verbrachte, schrieb der Komponist in wenigen Wochen sein d-moll-Trio nieder.

Es zählt bis heute zu den populärsten Beiträgen einer damals noch jungen Gattung, die mit Beethoven und Schubert erste Höhepunkte erlebt hatte. Die klassizistische Prägung, die Mendelssohn als Jugendlicher erfahren hatte, mischt sich in diesem Werk auf ideale Weise mit romantischem Überschwang, die Balance zwischen den drei Instrumenten ist vollkommen. Schon der Beginn mit seinem großen, auf ebenmäßige 16 Takte angelegten Cellosolo unterstreicht den bewusst konzertanten Charakter des Trios, der mit den Repliken der Violine und der gegenläufigen Klavierbegleitung zu einem spannungsvollen Miteinander entwickelt wird. Die innere Ruhelosigkeit der Musik, die nur selten zum Stillstand kommt, wird durch die melodischen Bögen gleichsam im Zaum gehalten; ihre scheinbare Schwerelosigkeit und die Durchsichtigkeit des Satzes mögen Schumann dazu bewogen haben, Mendelssohn – in Bezug auf dieses Trio – als den „Mozart des 19. Jahrhunderts“ zu preisen.

Wie die Übertragung eines Liedes ohne Worte vom Klavier auf das Klaviertrio wirkt das Andante, dessen idyllisch schwebende Melodie zuerst allein vom Tasteninstrument angestimmt wird, um dann im Duett der beiden Streicher wiederholt zu werden. Dieses Frage-und-Antwort-Spiel wird von einem nach Moll gefärbten, durch unruhige Triolenbegleitung gekennzeichneten Mittelteil unterbrochen. Den flüchtigen Charme der Geister und Elfen aus der Musik zum Sommernachtstraum beschwört das Scherzo mit rastloser Klavierbegleitung, unerwarteten Wechseln zwischen Pianissimo und Fortissimo und abrupt gegeneinander gestellten Melodiefragmenten. Im Finale lässt Mendelssohn Reminiszenzen an die vorangehenden Sätze anklingen: Die dramatische Energie erinnert an den Kopfsatz (in gleicher Tonart d-moll), die große Kantilene an das Andante. Mit einer brillanten Steigerung in strahlendem D-Dur schließt das Werk.

Ein Jahr vor dem Trio komponierte Mendelssohn sein Streichquartett D-Dur als letztes einer Dreiergruppe, die bald darauf als op. 44 publiziert wurde. Der stürmische Gestus der frühen Quartette op. 12 und op. 13 weicht hier einer eher klassizistischen Gelassenheit. Auch wenn im eröffnenden Molto allegro vivace die erste Violine unangefochten dominiert, ist der vierstimmige Satz doch ebenso dicht wie detailliert ausgearbeitet und austariert im Wechselspiel der Stimmen, wobei das wie emporgeschleudert wirkende Kopfmotiv allgegenwärtig bleibt. Tremoli und simulierte Paukenschläge im Cello verleihen der Musik ein quasi orchestrales Gepräge. Geradezu altmodisch wirkt dagegen das folgende Menuett – der einzige so bezeichnete Satz im gesamten Quartettschaffen Mendelssohns. Samtig schimmernde Klänge lösen sich im Trio in chromatische Girlanden der Violine auf, die von den anderen Instrumenten aufgenommen werden. Im Andante espressivo mischen sich einmal mehr Lied ohne Worte und Serenadenklänge. Eine Atmosphäre überschäumender Freude treibt das abschließende Presto voran: Im Stil einer neapolitanischen Tarantella jagen sich die Triolenketten, jeweils nur kurz innehaltend, um dann wieder in neue harmonische Richtungen davonzustürmen. Mendelssohn hielt dieses Werk für „feuriger und auch für die Spieler dankbarer als die andern“ Quartette aus op. 44. Als besonders dankbar sollte es sich für den Geiger Ferdinand David erweisen – für ihn schrieb Mendelssohn einige Jahre später sein Violinkonzert.

„Daher gelingen mir am besten Lieder...“: Fanny Hensel

Mit einer Gruppe von Liedern – hier in einer Fassung ohne Worte – ist im Programm dieses Wochenendes das vielseitige Schaffen Fanny Hensels vertreten, dem in den letzten Jahrzehnten die lange überfällige Wertschätzung zuteilgeworden ist. Der Widerspruch in ihrem Leben zwischen Können und Dürfen ist aus heutiger Perspektive nicht mehr nachvollziehbar: Einerseits genoss Fanny – ebenso hochbegabt wie ihr vier Jahre jüngerer Bruder – eine exquisite musikalische Ausbildung in Klavier, Geige und Komposition, andererseits blieb ihr der Weg zu einer professionellen Musikerinnenlaufbahn nach dem Diktum des Vaters versperrt, wie er der 15-Jährigen unmissverständlich klarmachte: „Die Musik wird für ihn [Felix] vielleicht Beruf, während sie für Dich stets nur Zierde, niemals Grundbaß Deines Seins und Tuns werden kann und soll.“

Gleichwohl hat Fanny im privaten Raum ihre Möglichkeiten zu künstlerischer Betätigung – insbesondere als Leiterin der von prominenten Gästen frequentierten „Sonntagsmusiken“ im herrschaftlichen Berliner Haus der Familie Mendelssohn – bestmöglich genutzt. Erst 1846, mit 41 Jahren, fand sie den Mut, als ihr Opus 1 eine Sammlung von sechs Liedern zu veröffentlichen. (Sechs weitere waren mehr als zehn Jahre zuvor unten Felix’ Namen erschienen.) Die Sammlungen op. 7 und op. 10 folgten dann bereits postum nach Fannys plötzlichem Tod durch einen Schlaganfall im Mai 1847. Als Textvorlagen wählte sie vielfach Gedichte zeitgenössischer Autoren wie Heinrich Heine, Nikolaus Lenau und Emanuel Geibel, deren Stimmung und Ausdrucksgehalt sie mit oft sparsamen Mitteln überaus wirkungsvoll in Musik setzte. („Daher gelingen mir am besten Lieder, wozu nur allenfalls ein hübscher Einfall ohne viel Kraft der Durchführung gehört“, schrieb sie selbstkritisch und vielleicht nicht ganz ohne Bitterkeit an Felix.) Die Lenau-Vertonung Vorwurf kontrastiert betrübte („Du klagst, dass bange Wehmut dich beschleicht“) und ermunternde Momente („O klage nicht“), während Im Herbste nach einem Text von Geibel mit intensiver Chromatik den schmerzlichen Gedanken an den Verlust des Geliebten ausmalt. Abendbild dagegen besingt die Freude über das „Lächeln der Holden“ in einer zarten Melodie über wiegenden Triolen des Klaviers.

„...virtuos-feuriges Musizieren“: Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Die Salzburger Konstellation von 1760 wiederholte sich 150 Jahre später in Wien: Mit patriarchalischer Strenge wacht Julius Korngold, einflussreicher Musikkritiker der Neuen Freien Presse, über die künstlerische Entwicklung seines Sohnes Erich Wolfgang. Dessen Talent blieb auch dem Dirigenten Bruno Walter nicht verborgen, der im selben Haus wie die Korngolds wohnte, wo „das virtuos-feurige und rauschende Musizieren des Wunderkindes stundenlang zu mir hinauftönte“. Damals ist Erich Wolfgang gerade einmal zwölf Jahre alt, und ein Jahr später, 1910, wirkt Walter höchstpersönlich an der Uraufführung von Korngolds Klaviertrio op. 1 mit. Engelbert Humperdinck, Komponist von Hänsel und Gretel, spricht von einem „Wunderkind aus dem Feenreich“, und märchenhaft mutet in der Tat der Erfolg des jugendlichen Komponisten an: Seine Schauspiel-Ouvertüre op. 4 bringt Arthur Nikisch in Leipzig zur Uraufführung, seine Sinfonietta op. 5 Felix Weingartner mit den Wiener Philharmonikern.

1930 war Korngold längst zum umjubelten Opernkomponisten aufgestiegen, als ihn eine Anfrage von Paul Wittgenstein erreichte, für den er 1923 bereits ein Klavierkonzert geschrieben hatte. Diesmal wünschte sich der Pianist ein Kammermusikwerk, woraus schließlich die fünfsätzige Suite für Klavier linke Hand, zwei Violinen und Violoncello op. 23 wurde. Wittgenstein, Sohn einer Wiener Industriellenfamilie (und Bruder des Philosophen Ludwig), hatte im Ersten Weltkrieg den rechten Arm verloren, dann jedoch mit eiserner Disziplin seine linke Hand für Konzertaufführungen trainiert. Bei der Komponisten-Prominenz seiner Zeit gab er verschiedene neue Werke in Auftrag, darunter neben Korngold auch bei Strauss, Prokofjew, Hindemith und Ravel.

In seiner Suite versteht es Korngold auf verblüffende Weise, dem Klaviersatz – nicht nur im Notenbild – die Illusion von zwei Händen zu geben. Er erreicht dies u.a. durch geschickte Verwendung des Pedals, das eine nahtlose Verbindung zwischen oktavierten Bässen und weichen Glissandi in hoher Lage suggeriert, oder den Einsatz des Daumens als „Drehachse“ zwischen Begleitung und Melodie. Nicht weniger als fünf Oktaven sind im Solopart, oft auf engstem Raum, zu überbrücken. Schon im einleitenden Präludium wird das deutlich. Sein quasi-barocker, wie improvisiert wirkender Duktus geht direkt in eine Fuge über, deren Cellothema das wohlbekannte B–A–C–H-Motiv aufnimmt, die später aber auch mit wienerischen Klängen aufwartet. Noch stärker in seinem Element ist Korngold im folgenden Walzer, der zwischen Sinnlichkeit, Morbidität und guter Laune changiert.

Mit „Groteske“ ist der dritte Satz überschrieben: Schneidende Dissonanzen treiben die Musik unerbittlich vorwärts und verzerren so den vorgegaukelten Humor. Ein kunstvolles Klaviersolo leitet zum scharfen Kontrast des elegischen Trios über. In Korngolds Lieblingstonart Fis-Dur steht der treffend als „Lied“ bezeichnete vierte Satz, der auf dem kurz zuvor komponierten Was du mir bist aus den Drei Liedern op. 22 basiert: ein sehnsuchtsvoller Gesang des Klaviers, der von den Streichern in zarten Farben umspielt wird. Mit Unisono-Oktaven im Klavierbass öffnet der Komponist den Theatervorhang zum Rondo-Finale. Ein schlichtes, beinahe an Schubert gemahnendes Cello-Thema macht den Anfang, nach mehreren Steigerungen ist noch einmal das Lied-Thema zu hören, eine weitere „groteske“ Variation und eine letzte Steigerung folgen, bevor das Hauptthema den Schlusspunkt setzt.

Mit dem Streichsextett D-Dur op. 10 gelangen wir zurück ins Jahr 1914. Während der Arbeit an den beiden Operneinaktern Der Ring des Polykrates und Violanta begann der 17-jährige Korngold mit der Komposition des Werkes, das allerdings erst drei Jahre später in Wien uraufgeführt wurde. Vorbilder und Inspiration sind nicht zu überhören: die Streichsextette von Brahms, Korngolds Lehrer Alexander Zemlinsky und Schönbergs Verklärte Nacht. Besonders auffällig ist die Spannung zwischen den tonalen Abschnitten, die immer wieder zum zentralen D-Dur zurückkehren, und den Abschweifungen in fernliegende harmonische Bereiche, deren Dissonanzen jedoch stets in den intensiven Fluss des Streicherklangs eingebettet sind.

Klar gegliedert mit drei Themen in unterschiedlichen Zeitmaßen ist der wuchtige Eröffnungssatz: Dem Beginn mit von der Viola angestimmten Triolenketten (Moderato) folgt ein durch hymnische Aufschwünge charakterisiertes Allegro und schließlich ein mit Tremoli unterlegter lyrischer Gedanke in ruhigerem Tempo – mehr als ausreichend Material, um ihm zwischen orchestraler Wucht und zarter kammermusikalischer Bewegung, zwischen Vorwärtsdrang und Innehalten eine Fülle von Stimmungen abzugewinnen. In faszinierende nächtliche Welten führt das Adagio; seine chromatischen Spannungen verdichten sich nach und nach zu einem kompakten Gebilde, das wie in einer unendlichen Melodie fortgesponnen wird, sich weiter intensiviert und zuletzt in G-Dur ätherisch verklingt. Wienerischen Charme verbreitet dagegen das Intermezzo mit seinem eingängigen Thema, dem angedeuteten – und raffiniert verfremdeten – Walzertakt, subtilen Tempoverschiebungen und Pizzicati. Das abschließende Presto gibt sich rustikal mit zwei vom Cello angestimmten Themen und einer hymnisch breit ausgespielten Episode. „Mit Feuer und Humor“, so die Spielanweisung, endet das Programm dieses musikalisch farbenreichen Wochenendes.

Der Berliner Musikjournalist Michael Horst arbeitet als Autor und Kritiker für Zeitungen, Radio und Fachmagazine. Außerdem gibt er Konzerteinführungen. Er publizierte Opernführer über Puccinis Tosca und Turandot und übersetzte Bücher von Riccardo Muti und Riccardo Chailly aus dem Italienischen.

The Artists

Elena Bashkirova

Piano and Artistic Direction

Elena Bashkirova studied piano at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Conservatory in the class of her father Dmitri Bashkirov and received further important guidance from Pierre Boulez, Sergiu Celibidache, Christoph von Dohnányi, and Michael Gielen, among others. Today she shares close and longstanding collaborations with artists such as Lawrence Foster, Karl-Heinz Steffens, Ivor Bolton, Manfred Honeck, and Antonello Manacorda. In addition to appearing as a soloist with major orchestras, she is a dedicated chamber musician and also regularly performs with singers including Matthias Goerne, René Pape, Robert Holl, Dorothea Röschmann, and Anna Netrebko. In 1998 she founded the Jerusalem International Chamber Music Festival, which she has led as artistic director ever since. In 2012, the festival established an annual companion program, Intonations, at the Jewish Museum Berlin. Together with the Jerusalem Chamber Music Festival Ensemble, Elena Bashkirova has performed around the world and at leading festivals. In 2020, she was appointed president of the Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Foundation in Leipzig, succeeding Kurt Masur.

December 2025

Michael Barenboim

Violin

Michael Barenboim is equally in demand as a soloist and chamber musician, performing on the violin and viola. He achieved his international breakthrough in 2011 with Arnold Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto conducted by Pierre Boulez, with whom he shared a long artistic and personal friendship. Since then he has appeared with some of the world’s leading orchestras, including the Vienna Philharmonic and Berliner Philharmoniker, Bavarian Radio Symphony, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Filarmonica della Scala, Philharmonia Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, and Los Angeles Philharmonic, collaborating with conductors such as Zubin Mehta, Gustavo Dudamel, and his father, Daniel Barenboim. He is concertmaster of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra and in 2019 founded the West-Eastern Divan Ensemble. He also recently co-founded the Nasmé Ensemble with a group of young Palestinian musicians, which will make its first appearance at the Pierre Boulez Saal later this season. Michael Barenboim is professor of violin and chamber music at the Barenboim-Said Akademie and served as its dean from 2020 to 2024.

December 2025

Madeleine Carruzzo

Violin

Madeleine Carruzzo was born in Sion, Switzerland, and completed her violin studies with Tibor Varga at the Detmold Academy of Music. From 1978 to 1981 she was concertmaster of the Tibor Varga Chamber Orchestra. In 1982, she became the first woman to join the Berliner Philharmoniker as a permanent member, performing with the orchestra until 2023. As a chamber musician, she has collaborated with Elena Bashkirova, Yefim Bronfman, Sir András Schiff, Radu Lupu, Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider, Renaud Capuçon, Nobuko Imai, Gérard Caussée, Frans Helmerson, and Boris Pergamenschikow, among others, and performed at the festivals of Salzburg, Lockenhaus, Schleswig-Holstein, and Jerusalem.

December 2025

Albena Danailova

Violin

Albena Danailova was born in Sofia into a family of musicians and began her musical training at the age of five in her hometown. She later studied at the Rostock and the Hamburg Musikhochschule with Petru Munteanu and attended master classes with Ida Haendel and Herman Krebbers, among others. After completing her studies, she joined the Bavarian State Orchestra as second, later as first violinist and eventually took over the position of first concertmaster in 2006. She held the same position with the London Philharmonic during the 2003–04 season. She has been concertmaster of the Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera since 2008 and of the Vienna Philharmonic since 2011.

December 2025

Yulia Deyneka

Viola

Russian-born Yulia Deyneka studied at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Rostock, and at Berlin’s University of the Arts. As principal violist of the Staatskapelle Berlin since 2005, she has received important artistic guidance from Pierre Boulez, Zubin Mehta, Sir Simon Rattle, Andris Nelsons, and many others. Her chamber music partners include Martha Argerich, Yo-Yo Ma, Gidon Kremer, Maurizio Pollini, Yefim Bronfman, Jörg Widmann, Radu Lupu, and Daniel Barenboim, with whom she has enjoyed a close collaboration for many years. She has been teaching at the Barenboim-Said Akademie Berlin since 2016 and was appointed a professor in 2019. At the Pierre Boulez Saal, she appears regularly as a member of the Boulez Ensemble and presented several concert cycles with the Berlin Staatskapelle String Quartet.

December 2025

Mohamed Hiber

Violin

Mohamed Hiber grew up near Paris and studied violin with Ana Chumachenco at the Escuela Superior de Música Reina Sofia in Madrid and the Munich Hochschule für Musik und Theater. A fellow of the Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation, he regularly performs with its ensemble, Mutter’s Virtuosi. He is one of the concertmasters of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, a position he has also taken as a guest with the Munich Philharmonic, Vienna Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra London, and Orchestre de Paris. As a soloist, he has appeared with Philharmonie Südwestfalen, Leipzig’s MDR Symphony Orchestra, the London Symphony, and the Czech Philharmonic, among others. A passionate chamber musician, Mohamed Hiber has performed with artists such as Daniel Barenboim, Yuri Bashmet, Martha Argerich, and Kian Soltani at the festivals of Salzburg, Lucerne, and Bonn, the Intonations festival in Berlin, and the Jerusalem International Chamber Music Festival.

December 2025

Ivan Karizna

Cello

Born in Minsk, Ivan Karizna began his musical education in his homeland, before studying at the Paris Conservatoire and completing his training with Frans Helmerson at the Kronberg Academy. A prizewinner of the Tchaikovsky Competition and the Concours Reine Elisabeth, he has recently appeared as soloist with the Berlin Radio Symphony under Vladimir Jurowski, the Dresden Philharmonic under Tabita Berglund, the Rotterdam Philharmonic, and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, among others. This current season, he performs the Dutch premiere of Thomas Larcher’s Cello Concerto with the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra at the Concertgebouw Amsterdam and makes his debut with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra. Chamber music programs will take him to the Ukaria Cultural Centre in Adelaide, Australia, and the Jerusalem International Chamber Music Festival, among others.

December 2025

Alexander Kovalev

Cello

Alexander Kovalev is principal cellist of the Staatskapelle Berlin and an avid chamber musician. Born in Moscow in 1992, he received his education at the Music School of Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Conservatory, the “Robert Schumann” Musikhochschule in Düsseldorf, and at the Hanns Eisler School of Music and the University of the Arts in Berlin. He has performed at renowned festivals such as the Euregio Music Festival, the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Festival, the Yellow Barn Festival, and the Verbier Festival and collaborated with artists including Martha Argerich, Daniel Barenboim, Patricia Kopatchinskaja, Roger Tapping, Nils Mönkemeyer, Fazıl Say, Mihaela Martin, and Natasha Brofsky. He regularly performs at the Pierre Boulez Saal as a member of the Boulez Ensemble.

December 2025

Adrien La Marca

Viola

Born in France in 1989, Adrien La Marca studied with Jean Sulem at the Paris Conservatoire, Tatjana Masurenko in Leipzig, and Tabea Zimmermann at Berlin’s Hanns Eisler School of Music. Since winning the 2014 Victoires de la Musique competition in France, he has performed across Europe, collaborating with the Orchestre National de France, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, and Les Siècles, among many others. Among his chamber music partners are Renaud Capuçon, Edgar Moreau, Pavel Kolesnikov, and the Van Kuijk, Hermès, and Ébène quartets. His most recent album featuring William Walton’s Viola Concerto and the world-premiere recording of Gwenaël Mario Grisi’s Viola Concerto, which was written for him, was released in 2020.

December 2025

Emmanuel Pahud

Flute

Swiss-French flutist Emmanuel Pahud received his education at the Conservatoire in Paris and at age 22 was invited by Claudio Abbado to join the Berliner Philharmoniker as principal flutist, a position he still holds today. As a soloist he has appeared around the world with many leading orchestras and conductors. His chamber music partners include Yefim Bronfman, Hélène Grimaud, Stephen Kovacevich, Jean-Guihen Queyras, and Éric Le Sage. Together with Le Sage and Paul Meyer, he founded his own summer music festival in Salon de Provence in 1993; he is also a member of the ensemble Les Vents Français. Committed to expanding the flute repertoire, he has regularly commissioned new works from composers such as Elliott Carter, Toshio Hosokawa, Philippe Manoury, Luca Francesconi, and Matthias Pintscher. He is a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music. Emmanuel Pahud teaches at the Barenboim-Said Akademie as a Distinguished Visiting Professor and was awarded Denmark’s Léonie Sonnings Music Prize in 2024.

December 2025

Astrig Siranossian

Cello

Cellist Astrig Siranossian studied at the Conservatoire in Lyon and with Ivan Monighetti at the Basel Music Academy. A winner of the Krzysztof Penderecki International Cello Competition, she has collaborated as a chamber musician and soloist with artists including Yo-Yo Ma, Sir Simon Rattle, Daniel Barenboim, Martha Argerich, Sir Antonio Pappano, Bertrand Chamayou, and Daniel Ottensamer, among many others. She has appeared in concert at the Philharmonie de Paris, the Vienna Musikverein, the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, the KKL in Lucerne, and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. She is artistic director of the festival Musicades in her hometown of Romans sur Isère, of the Adèle Clément Cello Festival im Department Drôme, and of the Nadia and Lili Boulanger Festival in Trouville-sur-Mer and has been teaching and the Paris Conservatoire since 2024. She was awarded the French Ordre national du Mérite earlier this year.

December 2025