Sir András Schiff Piano

Sir András Schiff plays on a Bösendorfer mahogany grand piano, model 280VC.

Program

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Adagio in C major for Glass Harmonica K. 356 (617a)

Johann Sebastian Bach

Ricercar a 3 (from The Musical Offering BWV 1079)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Fantasy in C minor K. 475

Piano Sonata in F major K. 533 (494)

Piano Sonata in B-flat major K. 570

Rondo in A minor K. 511

Adagio in B minor K. 540

Piano Sonata in C minor K. 457

Frédéric Chopin

Waltz in A minor Op. 34 No. 2

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Adagio in C major for Glass Harmonica K. 356 (617a)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Ricercar a 3 (from The Musical Offering BWV 1079)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Fantasy in C minor K. 475

Adagio – Allegro – Andantino – Più Allegro – Tempo primo

Piano Sonata in F major K. 533 (494)

I. Allegro

II. Andante

Piano Sonata in B-flat major K. 570

I. Allegro

II. Adagio

III. Allegretto

Rondo in A minor K. 511

Andante

Adagio in B minor K. 540

Piano Sonata in C minor K. 457

I. Molto allegro

II. Adagio

III. Allegro assai

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

Waltz in A minor WN 63

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, portrait by Barbara Krafft (1819)

“From the Depth of the Piano”

Sir András Schiff dedicates his concert series at the turn of the year to the musical masters who have most profoundly shaped his artistic outlook and five-decade career.

Seven composer's portraits by Wolfgang Stähr

“From the Depth of the Piano”

Seven Composers—Seven Portraits

Wolfgang Stähr

“A Witty Mind”

Joseph Haydn

There is no lack of crazy ideas, jests, jokes, and parodies, even unpleasant surprises and daring provocations, in Joseph Haydn’s piano music, whether from the Esterházy family’s young kapellmeister or the mature and prominent “Shakespeare of music” celebrated in England. “At the most cheerful of hours,” Haydn writes a lively fantasy, a presto—and suddenly the pianist stops playing. What has happened? Has he lost his way, forgotten the music, decided to quit? Elsewhere, Haydn composes a sonata and gives the uneasy impression in the finale that the pianist has made several glaring mistakes, veering into the wrong key. But that is exactly how the piece is written, correctly incorrect, a calculated miss, a game of wrong notes: unashamed enjoyment at the embarrassment caused by the unexpected moment. “What the British call humor” is described as one of Haydn’s main character traits by Georg August Griesinger, the composer’s late-in-life confidant and first biographer. “He easily discovered the comical side of any thing, and preferred that view, and anyone who had spent even an hour with him could not help but notice that spirit of Austrian national cheerfulness that animated him.”

Haydn, however, not only entertained his listeners with ironic jests and sarcastic interludes, but also and mainly with the higher understanding of art the British called “wit,” “the power of the mind,” or “quickness of fancy,” as Samuel Johnson puts it in his 1774 Dictionary of the English Language. Around just the same time, the Swiss cultural philosopher Johann Georg Sulzer dedicated an article to the joke (or “Witz” in German) in his Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste (General Theory of the Fine Arts) and arrived at the conclusion that, “A trivial incident, recounted by a witty mind, can be very entertaining. The most common thought, the description of the most mundane object, gains attractiveness through the influence of wit, which makes it most agreeable to persons of taste.” This is the wit inherent in Haydn’s piano music, in which he takes dry and brittle material such as broken chords or ostinato octave leaps and transforms them into uncommonly versatile, entertaining and discursive music, crafting themes resembling question and answer, thesis and antithesis: “most agreeable” indeed.

“And That Is True Skill”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Even though Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, unlike his father, was not a born music theorist and never authored tracts on music education, he did write down his views on musical taste, style, and interpretation: in his letters, he described the twin ideal of an art of performance that was equally true to the text and soulful. Mozart demanded unequivocally to play each piece “in the right tempo, as it should be. All notes, grace notes etc. should be delivered with the proper expression and gusto, as written, making the listener believe the player himself had composed it.” No note was allowed to be omitted when Mozart was watching his students (or colleagues), but most importantly, no note was allowed to be played without feeling, without heart, without soul.

That is why Mozart was not an admirer of the brilliant technique and keyboard virtuosity of a musician such as Muzio Clementi (with whom he had been asked to appear in a battle of pianists before Joseph II): “incidentally, he has not a groat’s worth of taste or feeling—a mere mechanic.” He was never a fan of the extrovert self-presentation of the virtuoso—on the contrary. “You know I am not a great lover of difficulties,” Mozart explained, only to praise the concertmaster of the Court Orchestra in Mannheim, Ignaz Fränzl, as the model of a masterful and unpretentious musician: “he plays difficult stuff, but one doesn’t recognize the difficulty, one thinks one could do the same. And that is true skill.”

“I Hope the Time Will Come”

Ludwig van Beethoven

Very few people know that Beethoven read the young Marx—and praised him explicitly: “Glancing through the pages, I noticed a few essays which I immediately recognized as the work of the ingenious Mr. Marx; I wish he continues always to uncover the sublime and the truth in the field of art; this might lead to the gradual diminishing of mere syllable-counting.” Beethoven had been reading the latest edition of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung from Berlin, whose editor was his esteemed Marx: Adolf Bernhard Marx from Halle, a jurist by training who felt that music was his real calling, had a few fleeting and local successes as a composer, but became an influential and respected writer, historian, and theorist. The “syllable-counting” so frowned upon by Beethoven, the paper-dry musicological “accountants’ analyses” with their arithmetic of groups of measures and their modulation schedules, were not to be banished by him either, at least not from the academic world.

Beethoven strove for the “sublime,” creating otherworldly, transfigured, speculative piano music that was not, however, devoid of wit and contradiction. It is music that goes to the heart without resorting to mawkishness or sentimentality, and that evidently produced a pianistic ideal of “molto cantabile,” as Beethoven wrote in a letter to the instrument-maker Andreas Streicher in 1896: “It is certain that the manner of playing the piano is still the most uncultivated of all instruments so far; often one thinks one is hearing nothing but a harp, and I prefer to delight in the fact that you are one of the few who see and feel that it’s possible to sing on the piano as well, as soon as one can feel; I hope the time will come when the harp and the piano are two totally different instruments.” That time did come, and Beethoven was its prophet, representative, and perfector. It will always remain a mystery why Igor Stravinsky believed that heaven withheld the gift of melody from Beethoven, only to grant it to Bellini in spades. A strange judgment indeed, to which the conductor Ernest Ansermet responded mockingly: “Perhaps when he said that, Stravinsky secretly thought he was defending himself against a future critic who might dare to say that at the beginning of this [20th] century, God gave Prokofiev the gift of melody while withholding it from Stravinsky. Perhaps he merely wanted to be in good company.”

“Whatever His Hand Touches”

Franz Schubert

Franz Schubert’s engagement with the piano sonata relatively late in life may be explained by the mundane fact that he had no keyboard instrument at his disposal, often composing “at the table” or having to walk to the Stadtkonvikt, his former boarding school, to try out new pieces at the piano. “He was plagued by pecuniary worries for years,” Josef von Spaun, a friend from his youth, reported, “indeed, he who was so rich in melodies could not afford to rent a piano.” His piano sonatas, however, give no evidence of these modest circumstances. Robert Schumann, who was one of the first to recognize the rank and character of Schubert’s sonatas, expressed a truth that was to remain controversial even into the recent past. Schubert’s piano music was long considered unpianistic. Schumann, on the other hand, proclaimed the exact opposite: Schubert was able to produce a “more piano-esque instrumentation” than most other composers, “meaning that everything resounds truly from the bottom, from the depth of the piano,” and discover notes to express “the most delicate feelings, thoughts, even anecdotes and life circumstances. As human writing and striving takes myriads of forms, so does Schubert’s music. Whatever his eye beholds, whatever his hand touches, everything turns into music.”

Not to mention when he touched the keys! “Hearing and seeing his piano compositions performed by himself was a true delight,” the Austrian civil servant Albert Stadler wrote in a tribute 30 years after the composer’s death. “Beautiful touch, a calm hand, clear, friendly playing, full of spirit and emotion. He was one of the old school of good piano players, the fingers not yet attacking the poor keys like pecking birds.” Schubert himself would doubtless have agreed with this lament about the deplorable custom of a rather too brisk pianistic attack. It was well-known he could not stand the “damnable chopping,” the ill-begotten bravura of even outstanding pianists: “it pleases neither the ear nor the mind.” Schubert was happy when grateful music lovers assured him, after a private concert in the summer of 1825, “that under his hands, the keys became singing voices.”

“You Must Play Something for Him!”

Robert Schumann

“There is nothing to be had from me,” Robert Schumann warned in a letter; “I hardly ever speak, more in the evening, and mostly at the piano.” Schumann’s legendary taciturnity or reticence soon became common knowledge, a much-discussed character trait of this composer who, at the same time, wrote utterly brilliant articles for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, which he also edited, never seeming at a loss for a witty turn of phrase. The rest, however, was silence. As it was on a day in late August 1846, when Schumann, who was living in Dresden at the time, received a visit from the music critic Eduard Hanslick from Prague—then quite unknown. At first, he still talked to his guest, though not about himself, but about Felix Mendelssohn: “What a pity that you didn’t arrive a few days earlier! Mendelssohn left for England yesterday. If only you had met Mendelssohn!” After this brief welcome marked by regret, the conversation, if it could be called that, soon ebbed into silence. Schumann exhaled the smoke of his cigar and followed the clouds of smoke rising to the ceiling with his eyes, lost in thought.

But just as Eduard Hanslick worried that his host was trying to “silence him away” and had made up his mind to leave, the visit took an unexpected turn. Schumann held him back, gently guiding him into the neighboring room and introducing him to his wife: “Clara! Mr. Hanslick from Prague is here; you must play something for him!” First, a new work was chosen, Schumann’s Studies for Pedal Piano, an instrument with a pedal attached as an additional bass register. Hanslick did praise the mastery, or, as one would have said in the 18th century, the compositional science of these six “pieces in canonic form.” And yet—“I longed for something different, one of the older pieces that had made Schumann dear to me. I asked for something from his ‘Sturm und Drang’ period. This expression, applied to his first compositions, astounded Schumann; he repeated it with a smile several times.” Indeed, Sturm und Drang by no means describes the prevailing temperament in Schumann’s early or earlier piano works, even if he spurred pianists on in one of his sonatas with absurd-sounding tempo markings: “as fast as possible—faster—even faster—presto—prestissimo—ever faster and faster.” Was this sadistic revenge on the pianists of this world? After all, Schumann himself had been forced to bury his dreams of a career as a virtuoso because of a paralytic weakness of his right hand and debilitating performance anxiety. His relationship with the grand masters of dexterity and bravura remained ambiguous throughout his life: on his desk, he assembled images of Paganini, Thalberg, and Liszt—but as caricatures, with octopus-like fingers and twisted spider legs.

“I Like to Take My Music Very Seriously”

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Res severa est verum gaudium—this quote by Seneca held pride of place, in large letters, on the back wall of the concert hall at Leipzig’s old Gewandhaus, Felix Mendelssohn’s long-time artistic home. “True enjoyment is a serious thing”: this fundamental moral exhortation became the motto of the Gewandhaus Orchestra in the bourgeois age, when seriousness, industriousness, and striving dominated all expressions of life, even the enjoyment of music. It almost goes without saying that Mendelssohn the Gewandhaus kapellmeister had no sense of humor and would not compromise as far as artistic matters were concerned. When a Viennese cousin of his, Katherine von Pereira, recommended that he set to music the ballad Die nächtliche Heerschau by Count of Zedlitz, which was extremely popular at the time, Mendelssohn rejected this proposal out of hand: “I like to take my music very seriously and consider it illicit to compose anything that I do not feel through and through. It’s as if I were expected to tell a lie; for after all, notes have as certain a meaning as words—perhaps even more certain.”

When people (and notably the publishers) asked to hear and play nothing but his Songs without Words, Mendelssohn protested this lopsided appropriation: “It would be good if one could play a different tune one of these days.” He, for one, followed this resolution with almost radical resolve in the summer of 1841, when he wrote the Variations sérieuses Op. 54, a commissioned work intended for a Beethoven tribute volume, itself to benefit the Beethoven monument being planned in Bonn. In choosing this title, Mendelssohn made it unmistakably clear that this work was not about fashionable, pleasing “variations brillantes”—such precious piano tinkling was out of question, given the holy earnestness of the cause. The theme alone displays all musical attributes of seriousness: the key of D minor, dissonant suspended notes, writing charged with chromaticism and syncopations, associations with funeral marches, church hymns, and all imaginable earnest affairs. Indeed, it seems to conjure a “Tombeau de Bach” rather than a “Monument for Beethoven.”

“Not to Evoke an Image of Common Death”

Johann Sebastian Bach

One evening in May 1832, Robert Schumann made his way to the Johannisfriedhof, “Leipzig’s wonderful graveyard.” Until nightfall, he traversed the sacred ground this way and that, in a futile attempt to locate the final resting place of Johann Sebastian Bach, kantor of St. Thomas, who died in Leipzig in 1750. He failed to find it: no grave, no marker, no trace. “When I asked the gravedigger about it, he shook his head at the man’s obscurity and said: there were many Bachs.” This heartless ignorance plunged the shocked Schumann into many conflicting emotions. At first, he consoled himself with a romantic thought: “How poetic is this coincidence! So that we shall not commemorate mortal dust, so as not to evoke an image of common death, it has blown the ashes in all directions.” Soon, however, his heart grew heavy at not having found Bach’s grave: “I could not place a flower on his urn, and Leipzig’s citizens of 1750 sank in my esteem,” he thought with bitterness.

But when, long after Schumann’s death, Leipzig’s citizens of 1900 rebuilt St. John’s Church in the Neo-Baroque style, they laid their former kantor to rest a second time. Following an ancient oral tradition, they searched for an oak casket said to contain Bach’s remains and located six paces from the south portal, unearthed it, and gave it a dignified resting place in the vault underneath the choir—finally. But not permanently. During World War II, air-raid bombs destroyed St. John’s too, and the sarcophagus could barely be salvaged from the ruined church and transferred to St. Thomas. There, it has rested to this day, and perhaps will until the Day of Judgment, for there may have been many Bachs, but this Bach was one of a kind. As Bach himself put it in his St. John Passion: Rest well, ye sacred bones.

Wolfgang Stähr, born in Berlin in 1964, has contributed chapters to books on Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, and Mahler. He regularly writes articles, essays, and program notes for the festivals of Salzburg, Lucerne, Grafenegg, Würzburg, and Dresden, for orchestras including the Berliner Philharmoniker and Munich Philharmonic, for Bavarian Radio, and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

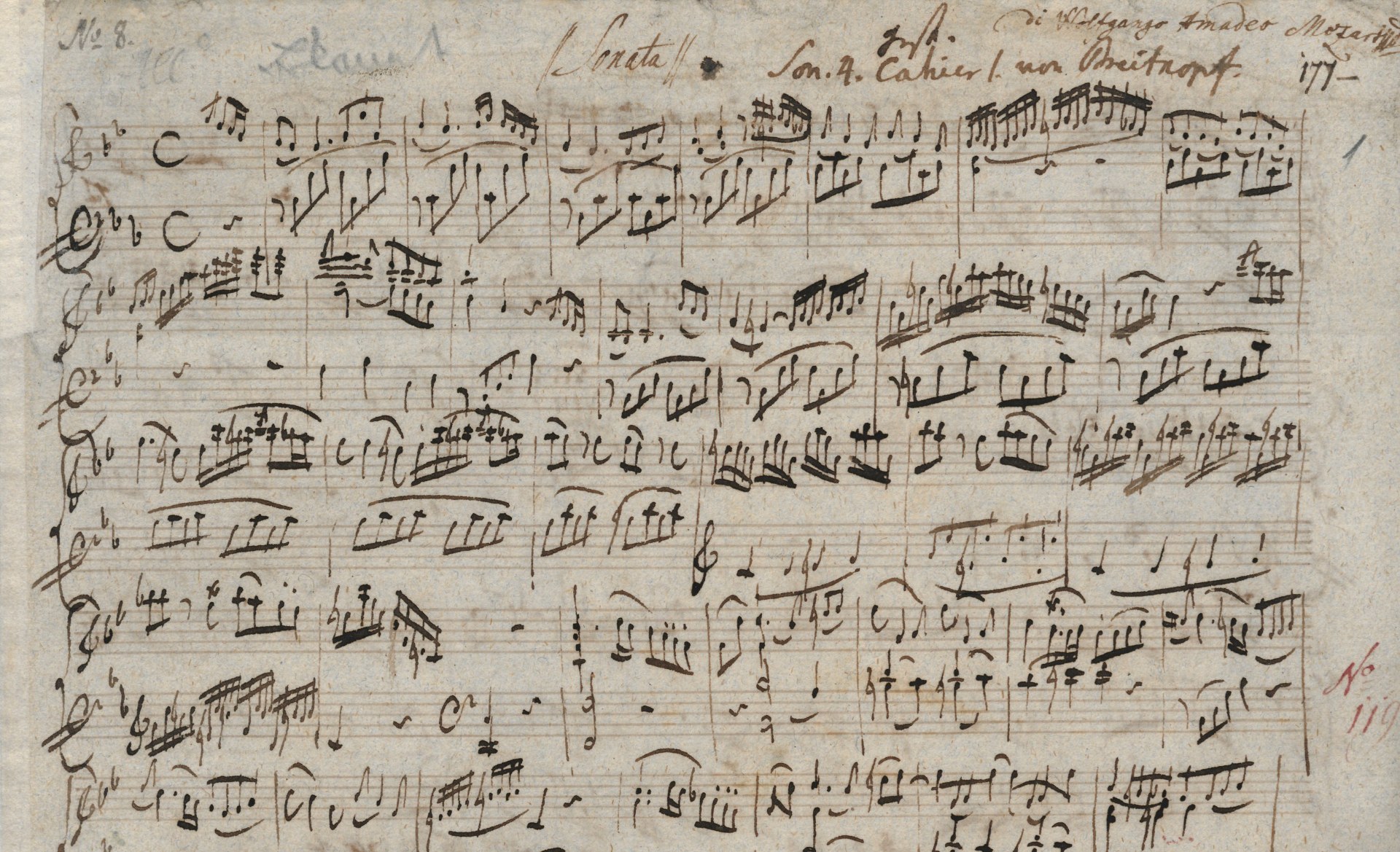

Mozart's manuscript of the B-major Piano Sonata K. 333 (315c) (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin)

The Fragment as Fulfillment

Sir András Schiff did not perform Bach's The Art of Fugue in public before he turned 70. In conversation with Monika Mertl, he talks about his admiration for the composer's fragmentary opus ultimum and why it was worth the wait.

The Fragment as Fulfillment

Sir András Schiff in Conversation on Bach’s The Art of Fugue

Sir András, you have taken decades to study The Art of Fugue, but only after your 70th birthday two years ago, you were ready to present it to an audience.

That was a very conscious decision. My relationship with Bach goes back to my childhood, when I started playing the piano. But from the time when I realized that Bach’s music would be the most important thing in my life, I started to systematically build the repertoire. And I knew I would be very grateful if God granted me the time and strength to play The Art of Fugue at 70. Now that time has come, and I want to keep going deeper and further—the journey never ends.

Is it true that you plan to reduce your repertoire until perhaps one day, only The Art of Fugue remains?

Yes indeed! My point is reduction to the essential. I would still like to learn a few pieces, I’m quite diligent and very curious, and I’m also fascinated by new music. But there’s very little that I like. A comet such as Mozart or Schubert only comes along once every 100 years. The constellation must be right; society and the arts are connected.

When looking at The Art of Fugue, it seems essential to me that the audience too understands what Bach called the “science of music”: he considered himself a scholar of music. His goal was not to compose as many successful works as possible, but to explore the possibilities of Baroque polyphony.

It was about science and faith. Religion plays an important role, not in the practical sense, but as a philosophy of the world—it’s not the ego, but the collective that is emphasized; he is writing for the congregation. And it’s about the interaction between art and science. Science has a beauty and poetry all its own. And in the arts, the intellectual aspect plays a major role, whether it’s architecture or music. I’m only fascinated by music in which emotion and intellect are in balance. In Bach, that’s the case to a high degree.

Bach composed “for the glory of God and the recreation of the mind,” as he himself put it—that’s a good characterization of these great fugue works, which are so breathtaking in their architecture and richness of invention, and of such compelling beauty of the same time.

So beautiful and so emotional! But at the same time, intellectually very, very demanding. As a great thinker, Bach was always setting himself new tasks. Consider the Well-tempered Clavier: two sets of 24 preludes and fugues, each prelude and each fugue in a different key; or the “Goldberg” Variations, another late work. Bach wasn’t particularly interested in variations, but all his contemporaries wrote virtuoso works in his genre, so toward the end he decided to demonstrate how to build such a fantastic, enormous work upon a very small theme. Everything is in G major here, but there are three variations in minor keys, for variety. Then his next to last composition, The Musical Offering, also based on an absolutely ingenious and very difficult theme, a huge work with a ricercar and a trio sonata… The Art of Fugue is the crowning glory of all that. Here, everything is in D minor, and it’s all based on a single theme—it’s a work entirely devoid of compromise.

During the last ten or twelve years of his life, Bach composed mostly for himself and without commissions, to create this life’s work of a “science of music.”

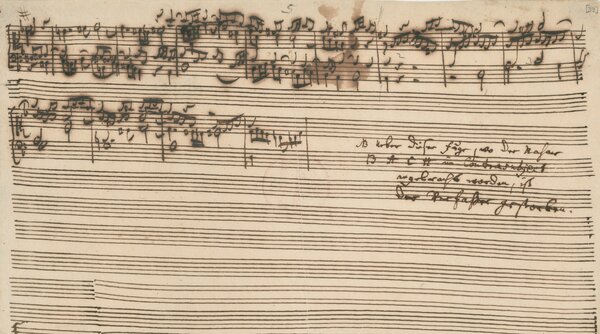

He also became a member of Mizler’s “Society of Musical Sciences,” to which Handel also belonged. Every member had to deliver a work for Mizler’s Musikalische Bibliothek [Musical Library], and it had to be not only musically, but also scientifically demanding. Bach intended The Art of Fugue to be his last contribution, but he didn’t finish it. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach claimed that his father died at the exact place where the last fugue suddenly breaks off, but this legend has increasingly come under doubt.

He probably had to invent an explanation. But Bach had this incredible ability to foresee a theme’s potential for development. Is it even possible he didn’t know how this last fugue would end?

He knew exactly. It was meant to be a quadruple fugue, B–A–C–H is the third subject, the one that puts his signature to the piece, and the fourth should have been the main theme, as set out in the first contrapunctus. Whether Bach stopped in measure 239 by coincidence or on purpose, who knows… I like to believe in the theory that the symbolism of numbers plays a role here: the cross sum of 239 is 14, the cross sum of the letters B–A–C–H is also 14, and then it’s also the Contrapunctus No. 14! For a very devout person of faith, it’s not allowed to blaspheme God by trying to be more perfect than Him! (laughs) Also, and I may be a romantic soul, but I find it breathtaking when the music just stops in midair. I think it’s a mortal sin to try to compose beyond this point. It’s a fragment—but what a fragment, taking an hour and a half to perform! Let’s be respectful and leave it at that. The fragment is in a category all its own.

The first version of The Art of Fugue, which Bach published in 1742, only contained ten contrapuncti and two canons…

This version came about because he had to deliver something for Mizler’s Society. The autograph score is such a thing of beauty, both graphically and visually—such an artful delight! The 1742 manuscript is still written on two staves, while the first edition is in the form of a score, on four staves and with different key signatures. Of course this is anything but a concert work.

You believe the form of the score is a clear indication it was intended to be a work for study, because is increases clarity?

Yes. What we think of as a concert today, much less of such dimension, didn’t even exist in Bach’s time. That raises the question whether The Art of Fugue should be played at all or if we should only study it. There’s only one answer: it would be a great shame if no one got to hear this greatest work in the history of music! But it was certainly not Bach’s intention.

Incidentally, the fugue fragment is by far the longest among the contrapuncti.

That’s because there’s an evolution—the first four contrapuncti are relatively simple, then come the fugues with stretto, then the double and triple fugues, and finally the mirror fugues. No. 14, as a quadruple fugue, was meant to be the crowning effort. The four canons are a kind of intellectual exercise to show what else can be done with this theme.

The canons are usually played at the end—when they’re not left out entirely.

I play them deliberately and I love doing so, but you have to place them in the right spot. I find it very beautiful when they are heard as inserts, because then you only have two voices, and in the fugues it’s usually four—that’s more exhausting, both for the audience and the performer. It’s certainly not a relief, the canons are very difficult. But in this way I can divide the contrapuncti according to their increasing level of difficulty. It simply works very well.

To me personally, the canons are more difficult to hear to than the contrapuncti, especially the “Canon per augmentationem in contrario motu,” which on top of everything else is also the longest piece in the entire cycle…

It’s true, that is very difficult to hear. But the most complex piece in the entire work is Contrapunctus 11, which further develops Contrapunctus 8: in No. 11, all three themes of No. 8 appear in reverse, and then there’s a fourth voice with the main theme. It’s simply incredible!

The two mirror fugues are also special works of art.

Just their visual appearance on the page alone would be fantastic, but then it also sounds as written! Even for someone like Bach this is enormously challenging. These two mirror fugues are at the limit of what is playable, and sometimes they go beyond. That also leads to the question which instrument Bach had in mind when he wrote The Art of Fugue. One thing is certain: this music was meant for a keyboard instrument. To me, The Art of Fugue consists of the art of composition on the one hand, and the art of playing on the other. It’s quite a feat for one person to play it—it’s not that impressive when a string quartet does it, or, God forbid, an orchestra.

As a solo performer, you can only play the mirror fugues consecutively. But there is a hypothesis that Bach conceived these pieces for two harpsichords together, which would make the mirroring audible simultaneously.

Bach first wrote No. 13 for one player: mirror fugue, rectus and inversus. That’s perfect, on the page and as a composition. But a harpsichord of course has no pedal, that’s why he made a version for two harpsichords. For two players, it’s actually quite easy. But for one, it’s courting disaster!

The notation of The Art of Fugue as a score also helped its discovery in the 20th century, thanks to the orchestral version Wolfgang Graeser prepared in the 1920s. Even if this seems stylistically inappropriate to you—Alban Berg raved about it, and the music world went wild with enthusiasm about this great music.

It was helpful actually, but those were different times, and today we’ve come a long way with historical performance practice and musicology. The most important thing is that The Art of Fugue is a solo work—the instrument we can talk about. And it can be played wonderfully on a modern grand piano. But it’s true that the two mirror fugues push the limits of what’s playable—in this case, using the pedal helps, which otherwise I very rarely do in Bach.

You’ve mentioned the visual appearance of the autograph several times. What inspiration have you drawn from it for your interpretation?

I own a facsimile of the autograph and all the sources, and this beautiful first edition of the final version in score form. I’ve studied them all very thoroughly. Admiration is not an adequate term for what I feel. What Bach achieved here is something that makes life worth living. It really makes you marvel at what human beings can do in science and in art. On the other hand, the speed of the development of Artificial Intelligence scares me. Art is made from those things that defy measurement—inspiration, mood, everything that cannot be analyzed. Artificial Intelligence absorbs all the information like a huge sponge, but there is not an atom of originality in it, only imitation. And if that gets out of control… We’ve already seen a computer beat the world champion in chess. With that, human beings lose their value. That’s something I cannot applaud. Why would one do such a thing?

Out of scientific ambition—but not “for the glory of God and the recreation of the mind.” When you play The Art of Fugue, one might say you’re defending the bastion of human thought.

I do consider it a privilege to be allowed to perform a work like this in today’s terrible world. When this music is heard, there is always a sense of community—for those 90 minutes, all’s right with the world. That’s not an escape, an ivory tower. There’s harmony in the world because such a fugue represents how society should be: it’s as if the voices are having a discussion, and none of them is more important than the other. Sometimes one of them takes the lead, two minutes later it might be a third, and the others play along or listen. Society can work like that as well—with patience, with tolerance.

Interview: Monika Mertl

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

The final page of Bach's manuscript of The Art of Fugue. The inscription, in Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach's hand, reads: "While composing this fugue, in which the name BACH appears as the countersubject, the author died."

The Artist

Sir András Schiff

Piano

Sir András Schiff was born in Budapest in 1953 and received his musical education at the Franz Liszt Academy in his hometown with Pál Kadosa, György Kurtág, and Ferenc Rados, and in London with George Malcolm. Recitals form a central part of his activities, particularly cyclical presentations of the works of Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, and Bartók. Since 2004 he has performed Beethoven’s complete piano sonatas in more than 20 cities. Having appeared with almost all major international orchestras and conductors over the course of his career, today he mostly performs as a soloist and conductor. With his own chamber orchestra, the Cappella Andrea Barca, which he founded in 1999, he has appeared at Carnegie Hall, the Lucerne Festival, and the Salzburg Mozart Week. His regular collaborators also include the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, the Budapest Festival Orchestra, and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Among his many awards are an honorary membership of the Beethoven-Haus Bonn, the Schumann Prize of the city of Zwickau, the Golden Mozart Medal of the Stiftung Mozarteum Salzburg, the Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, and the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society. In June 2014, he received a knighthood from the late Queen Elizabeth. Sir András Schiff teaches at the Kronberg Academy and since 2018 has been a Distinguished VisitingProfessor at the Barenboim-Said Akademie. At the Pierre Boulez Saal, he has presented several concert series, including performances of Johann Sebastian Bach’s major solo works.

December 2025