Alina Ibragimova Violin

Sindy Mohamed, Álvaro Castelló Viola

Laura van der Heijden Cello

Matthew Hunt Clarinet

Ben Golscheider Horn

Alasdair Beatson Piano

Program

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Horn Quintet in E-flat major K. 407 (386c)

Krzysztof Penderecki

Sextet for Clarinet, Horn, String Trio, and Piano

Béla Bartók

Contrasts for Clarinet, Violin, and Piano Sz 111

Ernst von Dohnányi

Sextet for Piano, Clarinet, Horn, and String Trio in C major Op. 37

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Horn Quintet in E-flat major K. 407 (386c) (1782)

I. Allegro

II. Andante

III. Rondo. Allegro

Krzysztof Penderecki (1933–2020)

Sextet for Clarinet, Horn, String Trio, and Piano (2000)

I. Allegro moderato

II. Larghetto

Intermission

Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

Contrasts for Clarinet, Violin, and Piano Sz 111 (1938)

I. Verbunkos. Moderato, ben ritmato

II. Pihenő. Lento

II. Sebes. Allegro vivace

Ernst von Dohnányi (1877–1960)

Sextet for Piano, Clarinet, Horn, and String Trio in C major Op. 37 (1935)

I. Allegro appassionato

II. Intermezzo. Adagio – Alla marcia quasi l’istesso tempo

III. Allegro con sentimento – Presto – Meno mosso –

IV. Finale. Allegro vivace, giocoso

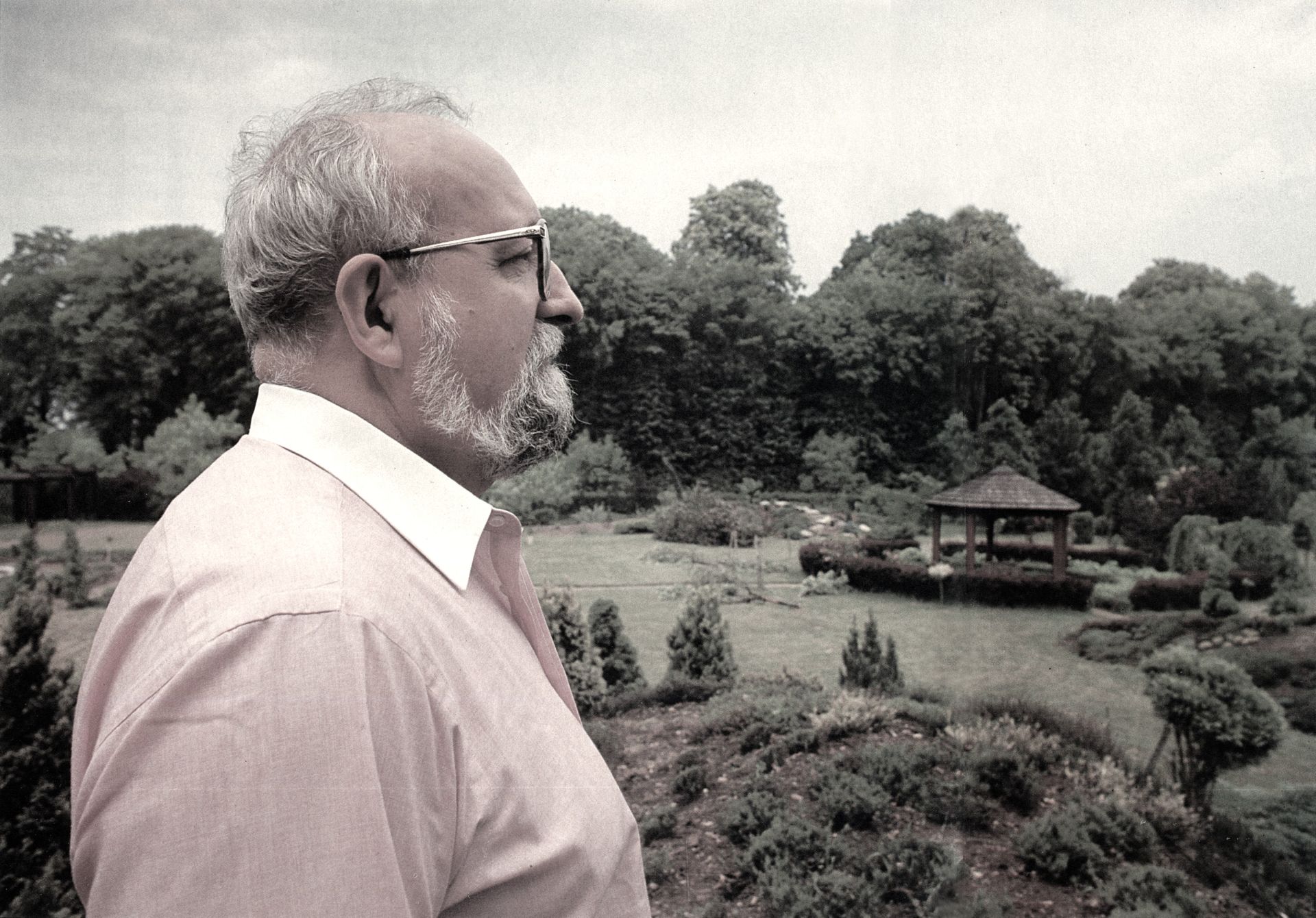

Krzysztof Penderecki, 1993

From Three to Six

The flexible, ever-changing possibilities of chamber music drive this evening’s program of music spanning more than two centuries. Personal friendships sometimes serve as the catalyst: Mozart’s Horn Quintet grew out of his playful rapport with the horn player Joseph Leutgeb, while Bartók’s Contrasts owes its origin to the persuasive efforts of violinist Joseph Szigeti.

Essay by Thomas May

From Three to Six

Contrasts and Combinations

Thomas May

The flexible, ever-changing possibilities of chamber music drive this evening’s program of music spanning more than two centuries. Personal friendships sometimes serve as the catalyst: Mozart’s Horn Quintet, for example, grew out of his playful, eccentric rapport with the horn player Joseph Leutgeb, while Bartók’s Contrasts owes its origin to the persuasive efforts of a longstanding friend, violinist Joseph Szigeti. Both works take an original approach to the chamber ensemble, with Mozart varying the string texture by doubling violas to balance the horn’s golden sound and Bartók relishing the stark contrasts between violin, clarinet, and piano.

A pair of rarely heard sextets from Eastern Europe expand chamber forces still further. Krzysztof Penderecki’s Sextet, the most recent composition on the program, distills a lifetime of experience into a multilayered drama of shadows and revelations. Ernst von Dohnányi’s stylistically versatile canvas, for its part draws from tradition but, with its surprising juxtapositions, embraces breadth.

Mozart’s Musical Friendship

Much as the clarinetist Anton Stadler, a friend and fellow Freemason, inspired some of Mozart’s most cherished instrumental works, the composer’s relationship with horn player Joseph Leutgeb played a crucial role in prompting significant additions to the horn repertoire. While Stadler was only a few years older than Mozart, Leutgeb, born in 1732, belonged to Haydn's generation and was known to Mozart since his childhood in Salzburg, where Leutgeb was a member of the court orchestra alongside the young Wolfgang. In 1777, four years before Mozart himself made the move, Leutgeb left Salzburg for Vienna to pursue his freelance career. Mozart maintained contact with him throughout his years in Vienna, right up until his premature death. Their rapport was playful and eccentric, involving a degree of mocking role-play in which Mozart would address the older musician with colorful epithets.

It was for Leutgeb that Mozart composed his four horn concertos and likely some standalone pieces, including the Concert Rondo K. 371. The Horn Quintet K. 407, his sole contribution to the genre, is also believed to have been written for Leutgeb. Probably dating from the end of 1782, the Quintet is a singular work that has been characterized as a chamber concerto for horn. However, Mozart departs from the conventional string quartet by scoring for a single violin and two violas with cello—a strategy that allows the violin to function as a solo counterpart to the horn, while the two violas serve to balance the sonic weight of the strings more effectively against the horn.

Despite the limitations of the natural horn (which requires hand-stopping to articulate notes outside the harmonic series), Leutgeb clearly possessed considerable agility and expressive capabilities, which Mozart exploits in the outer movements, and a glowing tone that is crucial for the Andante. The opening Allegro explores the ensemble’s various timbral possibilities: horn and violin, horn and cello, strings alone, and combined ensemble. Mozart cleverly alludes to the horn’s traditional association with hunting calls and signals, transforming this utilitarian sound into “pure” music through the use of a recurring rhythmic motif.

The Andante begins with strings alone but magically makes way for the horn to add its colors. Mozart segues from the dreamily lyrical character of this movement to a cheerful rondo finale, which uses an accelerated version of the Andante theme for some of its material.

At the Edge of Silence

“Today, having gone through the post-Romantic lesson and exhausted the potential of postmodern thinking, I see my artistic ideal in claritas. I turn to chamber music in the belief that more can be said softly, condensed into the tone of three or four instruments,” Krzysztof Penderecki reflected in 1993. “This escape into musical privacy might be an answer of sorts, our own fin-de-siècle response to the acceleration of history and to the turmoil of overturned norms in culture, ethics, and politics.”

This “escape” into chamber music gave rise to one of Penderecki’s most affecting later works: the Sextet for clarinet, horn, piano, and string trio, premiered at the Musikverein in Vienna in 2000. One of the preeminent voices of postwar Poland, Penderecki had first captured attention as a prodigy of the avant-garde, known for his radical experiments in texture verging on pure sound, as in his Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima (1960). Yet he would later observe that there was “more of destruction than of building anew” in his early approach. As he matured, Penderecki found renewed inspiration in the lessons and legacy of the musical past.

The Sextet is structured as a diptych, with the center of gravity in its much longer second movement. It opens with an ironic gesture recalling Shostakovich: an ominously expectant ostinato pattern from the piano that beckons the other instruments to join in with hints of a suppressed dance. The effect is fractured, even surreal, as Penderecki ratchets up the tension. A melodic phrase crystallizes, voicing an air of lingering regret, which is destined to serve as the main theme in the movement that follows. The first movement continues to unfold with kaleidoscopic invention and virtuosity, aspects of the dance denied occasionally flaring with renewed intensity until the music comes to a vehement close.

The ensuing Larghetto is more than twice as long as the opening Allegro moderato. Its main theme establishes a mood of introspective lamentation. Varying textural blends are used as variation devices to plumb the unsuspected implications of this material, while chromatic adumbrations enhance a sense of emotional saturation and complexity. Eloquent solos are artfully woven into this soundscape, with prominent roles for clarinet and horn and, later in the movement, the mournful song of viola and cello. Penderecki’s melodic transformations cast a spell throughout the duration of this deeply moving elegy. In its final minutes, the music recedes inexorably, reaching a destination of resigned inaudibility.

A Transatlantic Encounter

At first glance, few musical figures seemed less alike than the Hungarian modernist Béla Bartók and the American jazz icon Benny Goodman. Yet violinist Joseph Szigeti believed their collaboration could yield something remarkable and, in 1938, acted as intermediary, persuading Goodman to commission a trio for clarinet, violin, and piano from Bartók—already hailed as one of the most provocative voices in contemporary music.

Szigeti had long championed Bartók’s work and would later prove a crucial ally during the composer’s difficult exile in the United States. He likewise admired the astonishing range of “the king of swing”—as Goodman was known—which extended beyond swing into the classical world. Goodman, however, anticipated a relatively light, brief composition—suitable for recording on a two-sided 78 rpm disc. Bartók’s first version, a two-movement Rhapsody introduced at Carnegie Hall in early 1939, already exceeded those limits. Dissatisfied with its structure, he soon added a slow central movement and retitled the work Contrasts. The final version premiered at Carnegie Hall in April 1940, with Bartók himself at the piano.

Bartók was fascinated by the sonic possibilities of this unusual ensemble. Having recently explored coloristic extremes in his Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, he now embraced the sharp divergences between the clarinet, violin, and piano rather than smoothing them over. Contrasts—his only chamber work featuring a wind instrument—celebrates, rather than reconciles, their opposing timbres. Other “contrasts” in play are of course the stylistic ones between jazz—along with klezmer associations—and European chamber music, as well between folk fiddle playing and classical virtuosity.

The outer movements draw on Hungarian folk traditions: a rural recruitment dance (verbunkos) featuring a clarinet cadenza, and a fiery sebes finale, complete with a retuning of the violin to give the music an extra edge, plus a section in 13/8 meter. They frame a slow movement with haunting textures (pihenő or “Relaxation”), showing Bartók’s affinity for “night music” and, some suggest, even hints of Indonesian gamelan. Playfulness, virtuosity, and folkloric grit all collide in this deeply original masterpiece.

Traditions Reimagined

An important advocate of Bartók was his compatriot Ernst von (Ernő) Dohnányi, a versatile artist and cultural leader who bridged the era of Johannes Brahms and the Modernist innovations of the new century. Though only four years older than Bartók, Dohnányi was not an innovator but put an individual stamp on the Romantic tradition he had inherited. Brahms himself was an early champion and arranged for the Vienna premiere in 1895 of his Opus 1, the Piano Quintet in C minor—the product of a still-teenaged composer.

Dohnányi carried something of Brahms’s deep engagement with chamber music forward into the 20th century. At the same time, he won renown as an extraordinarily gifted pianist, calling to mind his predecessor Franz Liszt’s dual identity as a composer and virtuoso performer. Through his influential work as a conductor and teacher, he also echoed Liszt’s generosity in promoting new voices.

The Sextet, with its unusual scoring for the same forces Penderecki calls for in his work, dates from 1935. Its composition was possible only because the overworked Dohnányi was compelled by illness to pause from his overextended performance commitments as a pillar of Hungarian musical life. While its grand scale, cast in four movements, evokes the ethos of late-Romantic chamber music, the Sextet undertakes a kind of survey across dramatically different eras and styles. Despite its C-major tonality, the first movement, with its focus on the keyboard’s low register and almost Mahlerian sensibility, reflects the turbulence of the dark decade in which it was conceived. Styled as an Intermezzo, the second movement incorporates an unsettling march that reinforces the zeitgeist.

But Dohnányi takes a different tack in the Allegro con sentimento, which discovers renewed purpose and vitality in neoclassical transparency and virtuosity. There is even a place for a European’s nod to jazz in the good-humored, lively finale, with its ragtime-inspired writing for the clarinet and piano—a few years ahead of Bartók’s Contrasts. At the close, Dohnányi summons the theme from the first movement to round out the Sextet.

Thomas May is a writer, critic, educator, and translator whose work appears in The New York Times, Gramophone, and many other publications. Lucerne Festival’s English-language editor, he is also US correspondent for The Strad and program annotator for the Los Angeles Master Chorale and the Ojai Festival.

Ernst von Dohnányi, 1900

Klänge aus der Ferne

Sehnsucht und Leid, Utopie und Erlösung – dies sind zentrale Themen romantischen Denkens und künstlerischen Schaffens. Das Leiden an der ungeliebten Gegenwart, die sehnsüchtige Suche nach der Vergangenheit und die Hoffnung auf die Wiederkehr eines erlösenden goldenen Zeitalters haben im Laufe der Kulturgeschichte eine Fülle von Symbolen und Motiven hervorgebracht.

Essay von Michael Kube

Klänge aus der Ferne

Kammermusik des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts

Michael Kube

Sehnsucht und Leid, Utopie und Erlösung – dies sind zentrale Themen romantischen Fühlens, Denkens und künstlerischen Schaffens. Das Leiden an der ungeliebten Gegenwart, die sehnsüchtige Suche nach der Vergangenheit und die Hoffnung auf die Wiederkehr eines erlösenden goldenen Zeitalters haben im Laufe der Kulturgeschichte eine Fülle von Symbolen und Motiven hervorgebracht. Sie prägen nicht nur die Lyrik und Prosa des romantischen 19. Jahrhunderts, sondern auch die wortlose Instrumentalmusik, ohne dort allerdings ein bestimmtes Gefühl zu konkretisieren. In dieser Hinsicht eine Ausnahme bildet vor allem ein Instrument: das Horn. In wohl kaum einem anderen Klang findet die Idee der Ferne, die Unerreichbarkeit der Hoffnung so sehr ihren musikalischen Ausdruck. Zu den naheliegenden Konnotationen von Jagd und Wald darf ebenso die der Post gezählt werden – die in Schuberts Winterreise bezeichnenderweise keinen Brief bringt. Erinnert sei aber auch an die von Achim von Arnim und Clemens Brentano herausgegebene Sammlung deutscher Lieder, die 1806/08 in drei Bänden unter dem Titel Des Knaben Wunderhorn erschien. Das Horn (zumal noch ohne die erst später erfundenen Ventile) wirkt hier bereits wie ein Echo aus längst vergangenen Tagen.

Tatsächlich erfreute sich das Horn bereits im ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert einer gewissen Beliebtheit, obgleich es neben den Streichern und den gängigen Holzblasinstrumenten (insbesondere Flöte und Oboe) solistisch nicht im Vordergrund stand und die allermeisten Werke entweder von Hornvirtuosen selbst oder explizit für sie geschrieben wurden. Aber auch in Oper und Symphonie wurde die charakteristische Klangfarbe des Horns eingesetzt. Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart notierte 1784/85 während seiner politisch motivierten Haft auf dem Hohenasperg in den Ideen zur Ästhetik der Tonkunst: „Im Concert- und Opernsaale ist der Waldhornist zu unzähligen Ausdrücken zu gebrauchen. Er wirkt in der Ferne, wie in der Nähe. Lieblichkeit, und wenn man so sagen darf, freundschaftliche Traulichkeit, ist der Grundton dieses herrlichen Instruments. Zum Echo ist nichts fähiger und geschickter als das Horn.“

„…der Leitgeb, Esel, Ochs und Narr“

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart hatte eine besondere Beziehung zu den verschiedenen Blasinstrumenten und noch mehr zu ihren Spielern. Die 1777/78 in Mannheim und Paris komponierten Werke mit Querflöte entstanden für Ferdinand Dejean, der im Hauptberuf viele Jahre als Arzt für die Niederländische Ostindien-Kompanie in Asien tätig war. Noch in Salzburg schrieb Mozart ein Oboenquartett und ein Oboenkonzert für Giuseppe Ferlendis, einen Meister seines Instruments. Gegen Ende seines Lebens komponierte Mozart in Wien ein Quintett und ein Konzert für Anton Stadler, einen der ersten Virtuosen auf der neuen (Bassett-)Klarinette. Für wen das einzige erhaltene Fagottkonzert komponiert wurde, ist heute nicht mehr mit Sicherheit festzustellen.

Auch dem Horn widmete Mozart mehrere Werke, die alle Joseph Leitgeb zugedacht waren. Leitgeb wirkte bis 1763 unter Joseph Haydn in der Hofkapelle des Fürsten Esterházy, übersiedelte dann nach Salzburg und ging schließlich 1773 nach Wien. Dass er dort vor den Toren der Stadt eine Käserei betrieb, ist eine bis heute weit verbreitete Legende – wahr ist hingegen, dass ihn mit der Familie Mozart eine innige Freundschaft verband, sowohl mit Vater Leopold als auch mit Wolfgang Amadeus. Ihm muss Leitgeb mit seinem Wunsch nach einem oder mehreren Werken für Horn geradezu in den Ohren gelegen haben, denn im Autograph des Konzerts KV 417 findet sich ein liebevoll-spöttischer Kommentar: „Wolfgang Amadé Mozart hat sich über den Leitgeb, Esel, Ochs und Narr, erbarmt.“ Dass Mozart dem Hornisten auch ohne Orchesterbegleitung höchste technische und gestalterische Meisterschaft abverlangt, zeigt das Es-Dur-Quintett KV 407, über dessen Entstehung nichts Näheres bekannt ist. Die ungewöhnliche Besetzung mit zwei Bratschen anstelle von zwei Violinen gibt jedoch einen deutlichen Hinweis darauf, dass das Werk auch klanglich mit einer gestärkten Mittellage konzipiert war.

„Ich bin doch ein slawischer Komponist…“

Als der 26-Jährige Krzysztof Penderecki bei einem Wettbewerb des polnischen Komponistenverbandes im Jahre 1959 nach anonymer Einsendung der Partituren vollkommen überraschend alle drei ausgeschriebenen Preise zuerkannt bekam, war ihm quasi über Nacht, wenn auch zunächst nur in seiner Heimat, der Durchbruch zum gefeierten Komponisten einer noch sehr jungen Generation gelungen. Eingereicht hatte er die Psalmen Davids für Chor, Saiteninstrumente und Schlagwerk, Emanationen für zwei Streichorchester sowie Strophen für Sopran, Sprechstimme und zehn Instrumente – Werke, in denen er den Klangraum mit forschendem Blick und sicherer Hand experimentell erweiterte. Vor allem das serialistisch geprägte, einzelne Ereignisse pointierende Strophen ermöglichte Penderecki der Sprung über den Eisernen Vorhang hinweg nach Westeuropa und von dort in die Welt: Er erhielt einen Kompositionsauftrag für die Donaueschinger Musiktage 1960 und schrieb mit Anaklasis eine Partitur, in der die von ihm entwickelten Techniken erstmals zu einer neuartigen, vorerst den persönlichen Stil prägenden Synthese verschmolzen.

Waren dies noch Kompositionen mit einer vergleichsweise überschaubaren Aufführungsdauer, so entstand in den Jahren 1963/66 im Auftrag des Westdeutschen Rundfunks mit der Lukas-Passion erstmals eine Partitur beträchtlichen Umfangs, die sich für Penderecki in mehrfacher Hinsicht als Wendepunkt erweisen sollte. Mit seinen an prominenten Orten präsentierten Kompositionen war innerhalb nur weniger Jahre das Bild eines Bannerträgers der Avantgarde entstanden, das zur Uraufführung der Passion (im März 1966 im Dom zu Münster) nicht mehr recht passen wollte. Mit dem einhelligen Publikumserfolg machte sich bald Misstrauen gegenüber dem Komponisten und seiner Musik breit: In der Anerkennung wurde Anpassung vermutet, während Penderecki selbst nur wenige Jahre später im polnischen Fernsehen das Werk recht präzise in seinem Œuvre verortete: „Bei diesem Stück hörte ich auf, Material zu suchen.“ Dass Penderecki dann knapp ein Jahrzehnt später, ausgehend von seinem Violinkonzert, seine musikalische Sprache radikal in eine damals vollkommen neuartige und als unzeitgemäß empfundene postromantische Richtung wendete, wirkt heute nur konsequent.

In dieser neuen Sprache ist auch das formal groß angelegte Sextett für Klarinette, Horn, Streichtrio und Klavier gehalten, über das Penderecki anlässlich der Uraufführung im Wiener Musikverein bemerkte: „Das Sextett ist ein typisches Werk des Jahrhundertendes, indem es sich auf die Erfahrungen des ganzen 20. Jahrhunderts bezieht, in welchem verschiedene Stile entstanden sind. Die Meilensteine, die geblieben sind, sind Strawinsky, Bartók und Schostakowitsch in seiner Kammermusik. Diese Musik ist mir näher als zum Beispiel Messiaen oder der Zwölftonkreis; diese sind mir zu fremd, ich bin doch ein slawischer Komponist, dem es um die Übermittlung des eigenen Gefühls, des Ausdrucks geht; die Claritas in der Konstruktion ist sehr wichtig, aber ich habe keine Angst vor der persönlichen Note.“

„Über die Instrumentation habe ich öfter nachgedacht…“

Als eine Variante des seit der Wiener Klassik etablierten Klaviertrios erscheint im Lauf des 20. Jahrhunderts die Besetzung mit Klarinette und Violine – erstmals wohl mit der 1920 veröffentlichten Suite aus Igor Strawinskys Histoire du soldat, eine Bearbeitung, die im Umkreis des gelegentlich auch als Klarinettist auftretenden Schweizer Industriellen und Mäzens Werner Reinhart entstand. Doch ähnlich wie bei Mozart und seinem „Kegelstatt-Trio“ (für Klarinette, Viola und Klavier) generierte die neu formierte Besetzung keinen eigenen Werkbestand. Die am volkstümlichen Tonfall der Klarinette orientierten Trio-Partituren von Aram Khachaturian und Darius Milhaud, beide in den 1930er Jahren komponiert, blieben Einzelwerke ohne weitere Resonanz – ebenso wie Béla Bartóks Contrasts, die als Auftragswerk für Joseph Szigeti und Benny Goodman entstanden.

Dass Bartók die Besetzung zumindest als neuartig, vielleicht gar als problematisch ansah, geht aus einer Bemerkung in einem Brief an Szigeti hervor: „Über die Instrumentation habe ich öfter nachgedacht, man könnte damit irgendetwas machen.“ Der langsame zweite Satz wurde erst nach der Uraufführung im Januar 1939 in der Carnegie Hall hinzugefügt, ebenso wie der Titel des Werks, der das „Ergebnis eines mehrstündigen Kopfzerbrechens“ war (die ursprünglich zweisätzige Partitur war zunächst mit „Rhapsodie. Zwei Tänze“ überschrieben). Er trifft allerdings die eigentümliche Mischung aus volkstümlich-ungarisch inspirierter Melodik der Klarinette, dem eher klassischen Spiel der Violine (mit Pizzicato, Flageolett, Tremolo und Akkordgriffen) und einer zeitgenössischen Harmonik. Dass der Auftrag des vom amerikanischen „King of Swing“ an Bartók noch vor dessen Emigration in die USA erging, sollte freilich nicht verwundern: Goodmans Einspielung von Mozarts Klarinettenquintett und Klarinettenkonzert sind legendär, und auch andere Komponisten wie Aaron Copland, Morton Gould, Paul Hindemith, Malcolm Arnold und Francis Poulenc schrieben Werke für ihn.

„Form und Inhalt sind voneinander untrennbar…“

Weitaus besser bekannt als der aus Ungarn stammende Komponist Ernst von (Ernő) Dohnányi sind hierzulande zwei seiner Enkel: Klaus von Dohnanyi, ehemaliger Erster Bürgermeister von Hamburg (der sich eingedeutscht ohne Akzent schreibt und mit Betonung auf der zweiten Silbe ausspricht), und Christoph von Dohnányi, international renommierter Dirigent. Im Lebenslauf Ernst von Dohnányis lassen sich zahlreiche Begegnungen und biographische Querbezüge verfolgen, die für die Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts von Bedeutung sind: In jungen Jahren als musikalisches Wunderkind hervorgetreten, wurde er im Alter von 17 Jahren in die Kompositionsklasse von Hans von Koessler an der Musikakademie Budapest aufgenommen, wo er auf Béla Bartók traf; sein Opus 1, ein Klavierquintett, wurde von Brahms ausdrücklich gelobt. Später zählte Sir Georg Solti zu seinen Studenten, und auch sein Neffe Antal Doráti hatte eine erfolgreiche Laufbahn als Dirigent.

Dass es um Ernst von Dohnányi und sein kompositorisches Schaffen viel zu lange still wurde, ist der politischen Situation in Europa geschuldet. Im Jahr 1941 musste er als Direktor der Akademie zurücktreten – bis zuletzt versuchte er, die jüdischen Mitglieder der von ihm gegründeten Budapester Symphoniker zu schützen. Ende 1944 floh er selbst nach Österreich, vier Jahre später emigrierte er über Argentinien in die USA. Im kommunistischen Ungarn wegen seiner Flucht zum Kriegsverbrecher erklärt, wurde er mit seiner spätromantisch geprägten Musik im Zeichen der Nachkriegsavantgarde völlig aus dem Repertoire gestrichen und vergessen.

Bei dem im April 1935 abgeschlossenen, vier Sätze umfassenden Sextett op. 37 handelt es sich um Dohnányis letztes größeres und zugleich komplexestes Kammermusikwerk. Nach einem Klavierquartett, zwei Klavierquintetten und drei Streichquartetten, die allesamt standardisierten Besetzungen und Gattungen folgen, bricht das gemischte Ensemble des Sextetts gewissermaßen aus diesem Rahmen aus. Mit Klarinette, Horn, Streichtrio und Klavier erinnert die Partitur an ähnliche Kombinationen im Quintett-Format (hier dann ohne die für die mittlere Lage so wichtige Viola) etwa von Zdeněk Fibich (1893), Thomas Dunhill (1898) und Robert Kahn (1909). Dohnányi nutzt die Instrumente des Ensembles für Farbverläufe in erdigen Tönen, wobei er die Tonart C-Dur von Anfang an nicht strahlen lässt, sondern bewusst eintrübt oder in chromatische Sequenzen aufbricht. Es mag diese ungewöhnliche Dichte aus kompositorischer Idee und klanglicher Realisation gewesen sein, die auch einen Rezensenten der Uraufführung (am 17. Juni 1935 in Budapest mit Dohnányi selbst am Klavier) tief beeindruckt hat: „In dieser Musik ist der Vortrag so wesentlich und von ihren Elementen untrennbar, dass sie sich der Unterscheidung in formale und ästhetische Analyse verweigert. Form und Inhalt sind voneinander untrennbar. Wirft man sich allein auf die Form, stößt man auf den Inhalt; und blickt man auf den geistigen Inhalt, so findet man ihn in der raffinierten Formung begründet.“ Erst über den an dritter Stelle stehenden Variationensatz findet das Werk zu seinem eher heiter gefügten Finale – das auch als trotziger Abgesang auf eine längst verschwundene und dem endgültigen Untergang geweihte Kultur verstanden werden kann.

Prof. Dr. Michael Kube ist Mitglied der Editionsleitung der Neuen Schubert-Ausgabe sowie Herausgeber zahlreicher Urtext-Ausgaben und war von 2012 bis 2025 Mitarbeiter des auf klassische Musik spezialisierten Berliner Streaming-Dienstes Idagio. Seit 2015 konzipiert er die Schul- und Familienkonzerte der Dresdner Philharmonie. Er ist Juror beim Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik und lehrt an der Musikhochschule Stuttgart und der Universität Würzburg.

The Artists

Alina Ibragimova

Violin

Alina Ibragimova received her education at Moscow’s Gnessin Music Academy and at the Yehudi Menuhin School and Royal Academy of Music in London. Among her teachers were Natasha Boyarsky, Gordan Nikolitch, and Christian Tetzlaff. One of the most versatile violinists of her generation, she performs a wide-ranging repertoire from Baroque music to commissions and world premieres. She has appeared with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra, and Berlin’s Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester, among many others, collaborating with conductors such as Vladimir Jurowski, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, Jakub Hrůša, Robin Ticciati, and Daniel Harding. As a chamber musician and recitalist, she has been heard at major venues including the Vienna Musikverein, New York’s Carnegie Hall, and London’s Wigmore Hall, as well as at the festivals of Salzburg, Lucerne, Verbier, and Aldeburgh. Recent highlights include appearances at the BBC Proms with Bach’s Solo Sonatas and Partitas and as artist in residence with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Alina Ibragimova has enjoyed a long-standing artistic partnership with pianist Cédric Tiberghien and is a founding member of the Chiaroscuro Quartet, which regularly performs at the Pierre Boulez Saal. She plays a violin by Anselmo Bellosio, made around 1775 and generously provided by Georg von Opel.

May 2025

Sindy Mohamed

Viola

Born in Marseille in 1992, Sindy Mohamed graduated from the conservatory in her hometown before completing her studies at the Paris Conservatoire with Pierre-Henri Xuereb, at Berlin’s Hanns Eisler School of Music, and at the Kronberg Academy with Tabea Zimmermann. She is a prizewinner of the International Anton Rubinstein Competition and has performed with the Royal Northern Sinfonia conducted by Lars Vogt, Heidelberger Sinfoniker, at the Mannheim Castle Concerts, the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Festival, the Heidelberger Frühling festival, and at London’s Wigmore Hall. As a chamber musician and soloist, she regularly appears at the Moritzburg Festival, Schubertiade Schwarzenberg-Hohenems, the Kronberg Festival, the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, and the Folles Journées in Nantes, among others, collaborating with artists such as Renaud Capuçon, Isabelle Faust, Emmanuel Pahud, Jan Vogler, Elisabeth Leonskaja, and Kian Soltani. Highlights of the current season include a tour of Italy with Vivianne Hagner, Eckart Runge, and Matthias Kirschnereit as well as the release of her debut album recorded with pianist Julien Quentin. Sindy Mohamed is a member of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra and Ensemble as well as a regular performer with the Boulez Ensemble. Next season, she will be heard at the Pierre Boulez Saal as soloist with the Cairo Symphony and alongside mezzo-soprano Marie Seidler. She performs on a viola made by Matteo Goffriller in Venice, c. 1700, on loan from the Beare’s International Violin Society in London.

May 2025

Álvaro Castelló

Viola

Born in Seville in 2003, Álvaro Castelló began his studies with Jacek Policiński at the Fundación Barenboim-Said in his hometown and later studied with Diemut Poppen at the Escuela Superior de Música Reina Sofia in Madrid. He currently completes his studies with Simone von Rahden at the Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin. As a chamber musician, he has performed at the Mendelssohn Festival in Hamburg, Turina Festival in Seville, Pau Casals Festival in El Vendrell, and at IMS Prussia Cove in England. Solo engagements have taken him to the Sinfonietta 92, the Orquesta Bética de Sevilla, and Madrid’s Teatro Real. He has performed with the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra and the European Union Youth Orchestra and was previously heard at the Pierre Boulez Saal as a member of the Boulez Ensemble.

May 2025

Laura van der Heijden

Cello

A graduate of Cambridge University and Berlin’s Hanns Eisler School of Music, Laura van der Heijden studied with Antje Weithaas and Leonid Grokhov, among others. Since winning the 2012 BBC Young Musician Competition, she has been one of the most in-demand cellists of her generation. She has performed as a soloist with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the Aurora Chamber Orchestra, and the Britten Sinfonia, among others, and has appeared at the BBC Proms, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, and the Kissinger Sommer festival. Together with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, she premiered and recorded Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s Earth, Sea, Air in 2023. She is a member of the Kaleidoscope Chamber Collective and has worked as a chamber musician with Timothy Ridout, Antje Weithaas, the Doric String Quartet, and the Brodsky Quartet. This current season, Laura van der Heijden performs with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, among others, and gives recitals at the Cello Biennale Amsterdam and at Wigmore Hall in London.

May 2025

Matthew Hunt

Clarinet

Matthew Hunt began his musical training in Lichfield Cathedral Choir and later studied clarinet in Paris and at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. He has been principal clarinetist of Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen since 2007 and has also performed with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam. As a chamber musician, he regularly collaborates with Nicolas Altstaedt, the Belcea Quartet, and the Vienna Piano Trio, among others, and has released an acclaimed recording of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet together with the Elias String Quartet. Matthew Hunt has been Professor of Chamber Music at the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen since 2020.

May 2025

Ben Goldscheider

Horn

Born in London, Ben Goldscheider completed his studies with Radek Baborák at Berlin’s Barenboim-Said Akademie in 2020. He was an ECHO Rising Star in the 2021–22 season and has since appeared at some of Europe’s most prestigious venues, including Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, the Vienna Musikverein, Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie, London’s Wigmore Hall, and the Cologne Philharmonie. At the Pierre Boulez Saal, he regularly appears as a soloist and as a member of the Boulez Ensemble. He has premiered more than 50 new works for horn to date, including solo works and chamber music as well as horn concertos by Gavin Higgins and Huw Watkins, and has performed as a soloist with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, the London Mozart Players, and the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, among others. He has also collaborated with artists such as Daniel Barenboim, Martha Argerich, Sergei Babyan, Elena Bashkirova, Stephen Hough, Sunwook Kim, and Michael Volle and is a member of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. His discography includes a solo album in honor of the 100th birthday of British hornist Dennis Brain as well as horn concertos by Malcolm Arnold, Christoph Schönberger, and Ruth Gibbs. Ben Goldscheider has been artist in association at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama since 2023 and was appointed professor at the Royal Conservatory in Antwerp this year.

May 2025

Alasdair Beatson

Piano

Alasdair Beatson studied piano with John Blakely at the Royal College of Music in London and with Menahem Pressler at Indiana University. As a soloist and chamber musician, he performs on both modern and historical instruments. Solo appearances have taken him to the Britten Sinfonia, the Moscow Virtuosi, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and the Royal Scottish Symphony Orchestra, among others. This current season, he appears several times at London’s Wigmore Hall and, together with the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra, at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. In addition to the Classical and Romantic repertoire, he also devotes himself to contemporary music and has worked closely with George Benjamin, Harrison Birtwistle, Cheryl Frances-Hoad, Thomas Larcher, and Heinz Holliger, among others. Alasdair Beatson is artistic director of the chamber music festival Musikdorf Ernen in Switzerland and teaches at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire.

May 2025