Oksana Lyniv Conductor

Susan Zarrabi Mezzo-Soprano

Christopher Ainslie Countertenor

Alberto Acuña Almela Flute

David Strongin, Phoebe Gardner, Georgios Banos,

Salvatore Di Lorenzo, Ayda Demirkan, Mălina Ciobanu,

Jamila Asgarzade, Mariam Machaidze, Sijun Kim Violin

Álvaro Castelló, Gerald Karni, Sara Umanskaya,

Salvatore Di Lorenzo Viola

Johanna Helm, Tamir Naaman Pery Violoncello

Asa Maynard Double Bass

Raphael Alpermann Harpsichord

Program

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber

Battalia à 10

Vladimir Genin

Alkestis

World Premiere

Thea Musgrave

Orfeo II: An Improvisation on a Theme

Vladimir Genin

Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes

World Premiere

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644–1703)

Battalia à 10 (1673)

Sonata. Allegro – Die liederliche Gesellschaft von allerley Humor. Allegro – Presto – Der Mars – Presto – Aria. Andante – Die Schlacht. Allegro – Lamento der verwundten Musquetier. Adagio

Vladimir Genin (*1958)

Alkestis

Mono-Opera for Mezzo-Soprano and Strings on a Poem by Rainer Maria Rilke (2015/2023)

World Premiere

Prologos

Epeisodion I

Epeisodion II

Kommos

Epeisodion III

Epeisodion IV

Stasimon

Epeisodion V

Parodos

Epeisodion VI

Exodos

Intermission

Thea Musgrave (*1928)

Orfeo II: An Improvisation on a Theme

for Flute and Strings (1975)

I. Orfeo Laments

II. Orfeo Crosses the River Styx

III. Orfeo Calms the Furies

IV. Orfeo Searches amongst the Shades for Euridice

V. Orfeo Hears Euridice’s Pleas

VI. Orfeo Is Attacked by the Bacchantes

Vladimir Genin

Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes

Mono-Opera for Male Voice and Strings on a Poem by Rainer Maria Rilke (2017/2023)

World Premiere

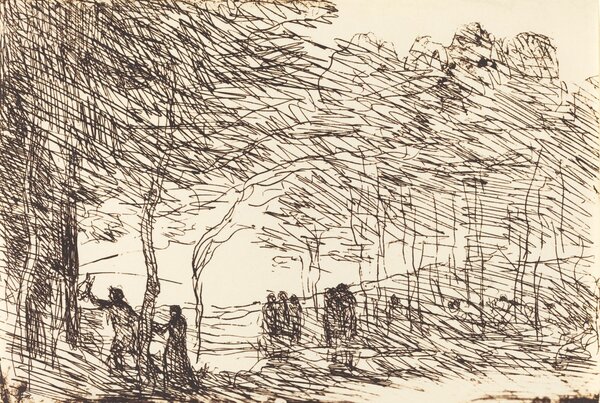

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Orpheus Leads Eurydice out of the Underworld (1860, © Creative Commons)

Myth into Music

Composers motivated by radically different ideologies and aesthetic beliefs embrace mythology as a fertile creative source. Led by Oksana Lyniv, the Boulez Ensemble explores connections between ancient stories and an all-too-real-present in the world premieres of two mono-operas Vladimir Genin and works by Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber and Thea Musgrave.

Essay by Thomas May

Myth into Music

The Boulez Ensemble Plays Biber, Genin, and Musgrave

Thomas May

Mythology, according to the writer Joseph Campbell, mediates a poetic experience of life: its foundation is narrative as metaphor, which means that there is no reducible “meaning” to, say, the ancient myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, but that it must constantly be interpreted anew. This inexhaustibility is one reason that artists of all disciplines and across the eras have remained so intensely attracted to the world of myth.

Composers motivated by radically different ideologies and aesthetic beliefs embrace mythology as a fertile creative source; without hesitation, they treat the very same mythic narratives that have frequently inspired their predecessors. The anxiety of redundancy—the worry that “it’s all been said before”—seems misplaced when a vital retelling of a familiar myth is at stake. Indeed, that familiarity itself can be used to advantage, since less energy must be expended on establishing the narrative framework: the artist can assume a baseline of knowledge and zoom in on new angles from the start.

In his two “mini-mono-operas” receiving their world premieres this evening, Vladimir Genin turns to a pair of myths that involve crossing the barrier between life and death. The story of Alcestis and her sacrifice to give her husband Admetus a lease on life, less familiar to contemporary audiences but a topic that inspired the likes of Lully, Handel, and Gluck, palpably addresses the fear of death. Orpheus’s journey into the Underworld to rescue his deceased wife Eurydice, on the other hand, assigns a special role to music and its promise of transcending loss and grief. This material became the foundational myth of opera itself and is ever present in our culture.

Biber’s Baroque Avant-Garde

Recognizing the power of music celebrated by the Orpheus myth also encouraged an idealized concept of non-representational “absolute music” that exists for its own sake—its only meaning rooted in the sounds and form of the work. In the later 19th century, this concept emerged in stark contrast to that of programmatic music, such as symphonic poems, which were seen to exploit the narrative potential of purely instrumental composition as a wordless counterpart to opera. But these different modes had long coexisted, particularly in the instrumental music of the Baroque, without being polarized.

As a prelude to the first of Genin’s operas, we hear an acclaimed example of such early program music. Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber published his Battalia in 1673, long before musical aesthetics became preoccupied with the debates around Richard Wagner’s “music of the future” and whether it had rendered such forms as the sonata obsolescent. Born in Bohemia in 1644, Biber earned a reputation as the preeminent violin virtuoso of his time, but he was additionally a virtuoso composer who could move effortlessly across genres, producing large quantities of secular and sacred music, vocal and instrumental alike.

In 1670, Biber embarked on his long and illustrious period of association with the court at Salzburg, where he completed the “Mystery” (or “Rosary”) Sonatas—a work that has proved especially resonant in the contemporary rediscovery of this composer. Battalia similarly intrigues because of its treatment of the perennially relevant theme of war and on account of Biber’s deployment of Baroque extended playing techniques that sound avant-garde even to 21st-century ears.

Though a young child at the end of the brutal Thirty Years’ War that had ravaged central Europe, Biber came of age amid its lingering aftereffects. He was hardly the first to depict impressions of war mimetically in a composition—Monteverdi’s Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda precedes it by half a century—but Biber’s specific attention to unusual sonorities to evoke these impressions is strikingly original. Although he uses conventional tropes such as marching gestures as well, these are only a part of his arsenal. For example, a movement comprising eight folk songs heard simultaneously in clashing keys and rhythmic tracks represents a bird’s-eye view of drunken merchant troops regaling themselves across the camp and is often compared with one of Charles Ives’s sound collages. Elsewhere, the violent shock of a snapped pizzicato to conjure the danger on the battlefield anticipates Bartók’s string technique. But rather than conclude with an ideologically correct salute to the “glory” of war, Biber pointedly offers a “lament of the wounded musketeers” in Battalia’s final section.

New Poems, New Myths

“Rilke has fascinated me since I was a conservatory student,” recalls Vladimir Genin. The Moscow-born composer’s admiration has only intensified over the years, as he went from reading the poet in Russian translation—he notes that Rilke himself wrote some verse in (not error-free) Russian—to appreciating him in the original German. Born into a family of composers and artists, Genin settled in Munich in the late 1990s and has pursued a wide range of interests as a composer, from chamber pieces to music for the stage and screen: his score for the 2001 film The Cosmonaut’s Letter earned him broader fame.

Rainer Maria Rilke (who died in 1926 at the age of 51) holds special importance for our own era, according to Genin, because of his gift for locating themes and angles in the quarry of myth that make them feel particularly present to us. Moreover, Genin perceives a natural theatrical quality in the poems he chose as the sources for his two mono-operas: Alkestis and Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes (as the mythic names appear in their German spellings). These are among the longest poems in the landmark collection Neue Gedichte (“New Poems”), published in 1907, which bears the deep imprint of Rilke’s inspiration from Auguste Rodin and Paul Cézanne, artists for whom he had a special affinity.

Genin particularly admires how Rilke treats these myths in a unique way to home in on the psychological truths embedded within them. His mono-opera Alkestis, written in 2015, confronts not only the terror of death but the limits of what we know about those closest to us. “The whole story is very dramatically told,” observes the composer. “Rilke’s text is more than a poem,” he adds, “but also resonates with a powerful dramatic sensibility.” To highlight this, Genin has subdivided the text into the sections comprising a classical Greek tragedy (including episodes in which the plot unfolds, sections and songs for the chorus, and ending with an exodos of closing choral ode).

In the myth, when King Admetus learns that he must die “within the hour,” he begs for a way out by providing a substitute. Rilke compresses the drama, locating the terror of the moment. “He shows Admetus to be a cowardly ruler,” says Genin. Although his new young wife Alcestis appears only near the end, after he has been disappointed by his parents and best friend, she is the poem’s transformative presence and “changes the whole picture.”

Musically, according to the composer, Alkestis tends toward a spartan simplicity that has an “archaic” flavor. The solo mezzo-soprano represents all the dramatis personae and, with the string orchestra as a counterpart, the chorus as well. Overall, Genin tends to alternate between various stylistic directions in his music, blending tonal and atonal language and using expressive devices like sprechstimme according to the needs of the text and dramatic situation.

Orphic Variations

Far better known than the premature journey into the Underworld that Alcestis agrees to take for the sake of her husband is the one dared by Orpheus in despair over the loss of his beloved Eurydice. That his musical prowess allows the hero to get around the strict laws of admittance has made Orpheus endlessly appealing to composers. Orfeo II is actually one of a constellation of works in which the Scottish-American Thea Musgrave has been inspired by the myth.

Musgrave is another contemporary composer who has engaged deeply with Greek myth in such works as Narcissus, Circe, and Voices of the Ancient World. But instead of an opera, Orfeo II is an instrumental work that alludes in its refraction of familiar melodies to Gluck’s operatic treatment of the story—a contemporary “improvisation” on a theme. In 1975, Musgrave composed a piece, Orfeo I, for James Galway featuring solo flute and tape, the latter an electronically processed recording of the flutist on different members of the instrumental family.

Orfeo II redistributes the tape part among a string ensemble, while the solo flute is again symbolic of Orpheus. But Musgrave wonders whether his odyssey to retrieve Eurydice might be only imaginary and introduces the quotations from Gluck as emblems of his memory. The failure of his attempt is clear at the end, as he mourns the loss of Eurydice.

Many variants of the core Orpheus myth exist. In Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes, Rilke uses a close-up focus on the narrative moment when Orpheus looks back at Eurydice—depicted here as being accompanied by the messenger-god Hermes—to open a startling new perspective on this critical turning-point that transforms the story into tragedy (although both Monteverdi’s and Gluck’s treatments allow for a “happy ending”).

Much as Alcestis shifts the dynamics of the scenario from the male perspective of Admetus in Rilke’s version, the poet’s depiction of Eurydice introduces a consciousness that Orpheus had not anticipated: one informed by her experience of death. “Because of that experience, Eurydice is now totally different and can no longer be his wife,” says Genin. One reason he chose these poems as topics for his mono-operas is because of the originality and power of Rilke’s characterization of the female protagonists: “They aren’t just heroines—they actually think differently from the rest, and the others in turn don’t understand them. And it becomes apparent that men who think they understand the Other don’t understand anything. Both pieces are really about human relationships.”

Again, the string ensemble represents the chorus: in Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes, the musicians even recite some phrases from Rilke’s poem to help establish the “secret and mysterious environment” of the Underworld through echo-like repetitions. The solo male vocalist encompasses a baritone-countertenor range, while Eurydice herself, perhaps represented by the solo violin, is given only one word (“Who?”) that dramatically underlines the unbridgeable gulf separating her from Orpheus.

The tragedy this illuminates, for Genin, is that “people don’t recognize each other and cannot understand what the Other is experiencing.” Referring to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and our sense of living in a time of crisis, he points out that such insights in Rilke’s poetry leap out with greater urgency than ever.

Thomas May is a writer, critic, educator, and translator whose work appears in The New York Times, Gramophone, and many other publications. The English-language editor for the Lucerne Festival, he also writes program notes for the Ojai Festival in California.

Vladimir Genin

In der Unterwelt

Unter der Leitung der ukrainischen Dirigentin Oksana Lyniv erkundet das Boulez Ensemble Verbindungen zwischen antiker Mythologie und unserer allzu realen Gegenwart. Im Zentrum des Programms stehen die Uraufführungen zweier Mono-Opern von Vladimir Genin; ihnen voran erklingt Musik von Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber und Thea Musgrave.

Essay von Wolfgang Stähr

In der Unterwelt

Musik und Drama von Biber, Genin und Musgrave

Wolfgang Stähr

Avantgarde, 1673

Der modernste Komponist, der die neueste Musik schrieb und die fortschrittlichsten Ideen verfocht, lebte in vormozartischer Zeit in Salzburg, brillierte als Violinvirtuose und stieg die Karriereleiter hinauf bis zum Hofkapellmeister: Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber, ein böhmischer Migrant. Hört man 350 Jahre später seine waghalsige Musik, muss man feststellen: Er war Charles Ives und Arnold Schönberg in einer Person. Und er war obendrein Witold Lutosławski, und John Cage war er auch noch. Er ließ sich avantgardistische, atonale, aleatorische Stücke für präparierte Instrumente mit Hang zum Happening und Nähe zum Nonsens einfallen. Und obgleich er mit der Battalia von 1673 ein längst etabliertes Genre tönender Schlachtengemälde aufgriff, boten ihm das kriegerische Personal und die martialischen Sujets ideale Spielräume für seine fantastischen Eingebungen und verstiegenen Experimente. Dass er dem Militär nicht mit übertriebener Ehrfurcht begegnete, hatte Biber bereits einige Jahre zuvor in seiner Sonata representativa bewiesen, in der neben Kuckuck, Frosch, Henne, Wachtel und Katze das „Mußquetir“ zu Gehör kommt.

Diese schießwütigen und vor allem trinkfreudigen Herren der Infanterie haben auch in der Battalia ihren großen, wenngleich denkbar unheroischen Auftritt: Schon der Untertitel des Werks kündigt wie zur Warnung „das liederliche Schwärmen der Musquetirer“ an. Aber bevor es so weit kommt, eröffnet eine Sonata mit irrem Wechsel aus Trommelrhythmen, Signalen, Fanfaren und Volksliedfetzen die acht Sätze für zehn Stimmen: drei Violinen, vier Violen, zwei Violoni und Basso continuo. Biber lässt die Streicher „col legno“, also mit dem Bogenholz spielen: „Wo die Strich sindt mus man anstad des Geigens mit dem Bogen klopfen auf die Geigen“, erklärt Biber in der Partitur. Dieser Einleitung folgt der erste Kulturschock: „Die liederliche Gesellschaft von allerley Humor“, ein Quodlibet (zu Deutsch: „was beliebt“), bei dem acht Melodien gleichzeitig in verschiedenen Ton- und Taktarten kreuz und quer durcheinander gespielt werden, ein dissonantes Zechgelage und eine subversive Absage an jede Art von Harmonie.

Nach einem fetzigen Presto wird dem Kriegsgott Mars gehuldigt, und zwar mit einem bizarren zweistimmigen Satz: Während sich die Violine in den wildesten, freiesten Improvisationen austobt, bleibt der Bass mit einem Streifen Papier zwischen den Saiten auf den dumpfen Part der „Druml“ fixiert. Noch ein Presto, dann eine Aria über ein Marienlied (Gebet vor der Schlacht), bis schließlich die eigentliche „Battaglia“ beginnt, zu deren realistischem Soundtrack auch Kanonenschüsse gehören, deren Donnerschlag Biber mit einem Trick suggeriert, wenn die Saiten geräuschvoll auf das Griffbrett knallen. Dieser harsche Effekt wird gewohnheitsmäßig mit Béla Bartóks innovativen Spieltechniken identifiziert und deshalb als „Bartók-Pizzicato“ bezeichnet. Aber wie wir sehen und hören, handelt es sich in Wahrheit um ein „Biber-Pizzicato“. Nachdem die Schlacht geschlagen ist, lassen sich auch wieder die sangesfreudigen Kriegshelden vernehmen, doch diesmal mit einem „Lamento der Verwundten Musquetirer“, dessen unheilvoller Ausdruck Biber zu den abwegigsten chromatischen Fortschreitungen reizte. Ein buchstäblich fortschrittliches Komponieren: Neue Musik aus dem 17. Jahrhundert! Und in ihren musikalischen Freiheiten und kabarettistischen Frechheiten zugleich eine hemmungslose Persiflage auf Kriegsverherrlichung und Heldengedenken.

Unsere Zeit, sogar die Kriegszeiten

Kann ein Komponist im Jahr 2023 noch moderne Musik schreiben? Vladimir Genin hat seine Zweifel an diesen Attributen, „modern“, „zeitgemäß“, „gegenwärtig“, und kommt zu einer paradoxen Antwort: „Vor lauter Angst, als altmodisch abgestuft zu werden, wollen die meisten nicht erkennen, dass das, was früher modern und rebellisch war, heute längst zu einem abgestorbenen akademischen Dogma geworden ist.“ Doch fürchtet Genin keineswegs, dass er als Komponist gar nichts Neues, Eigenes, Unverwechselbares mehr mitteilen könne: „Jeder Mensch ist ein Unikat, und wenn er sich selbst offenbart, mit all seinen Gefühlen und Gedanken, dann wird seine Musik zwangsläufig etwas Individuelles haben.“

Aber wer ist dann überhaupt noch „modern“? Rainer Maria Rilke: Er ist ein moderner Dichter, sagt Genin. „Seine Themen sind gegenwärtig. Er hat die Mythen aufgegriffen, in denen ewige Themen behandelt werden. Insofern spiegeln seine Verse auch unsere Zeit, sogar die Kriegszeiten.“ Schon als Student am Moskauer Konservatorium las der 1958 geborene Genin Rilkes Lyrik (zunächst noch in russischen Nachdichtungen) und entdeckte unter den Neuen Gedichten von 1907 die Werke über Alkestis und über Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes, ja er begann damals bereits mit einer Vertonung, einstweilen aber nur versuchsweise wie ein Gedankenspiel. Doch als Genin nach Deutschland kam (er lebt seit 1997 in München) und die deutsche Sprache erlernte, wagte er sich schließlich an die beiden Originale: Rilkes mythologische Gedichte, in denen Genin ein enormes dramatisches Potential erkannte, spannende Handlungen über menschliche Beziehungen, den zündenden Stoff zur Dramatisierung und die besten Vorlagen für ein Monodram oder eine Monooper in der Nachfolge von Francis Poulencs Ein-Personen-Stück La Voix humaine, bei dem nur eine junge Frau allein auf der Bühne zu sehen ist und ein Telefon als Symbol des einseitigen Dialogs und der unerwiderten Liebe fungiert.

Aber Genin denkt nicht an eine traditionelle Aufführung im Theater, noch weniger an eine starre Abgrenzung zwischen Podium und Publikum; er stellt sich vielmehr ein gemeinsames Erlebnis vor, eine Feier, ein Mysterium. Genin möchte mit einfachen szenischen Mitteln und doch ohne Inszenierung den geistigen Raum, die Form, die Stationen der griechischen Tragödie nachbilden, etwa wenn Orpheus, der nach Eurydike sucht, durch das Orchester wandert oder wenn die Musiker:innen einzelne Sätze sprechen, als Echo und Widerhall. Und als „griechischer Chor“, den sie auch sprachlos verkörpern, da sie rein mit der Musik, ohne ein Wort, auf das Geschehen reagieren. Und obgleich Genin seine Monoopern schon vor einigen Jahren komponiert hat, als er den Schauplatz der künftigen Uraufführung noch gar nicht kannte, empfindet er die Wahl des Pierre Boulez Saals als Glücksfall: „Ein idealer Raum für diese Stücke, nicht zu groß und rund wie eine griechische Arena.“ Musikalisch bewegt sich Genin „zwischen den Stilrichtungen“, wie er betont. „Ich bin nicht einer bestimmten Linie zuzuordnen. Es gibt häufig tonale Passagen, die Tonalität ist für mich ein wichtiges Ausdrucksmittel. Aber es gibt auch atonale Teile, und beim Vokalpart setze ich auch die Sprechstimme ein. Manche Abschnitte klingen minimalistisch, aber ich verwende das nicht als Stilmittel, das immer da ist, sondern ich setze Elemente verschiedener Stilrichtungen zu einem Puzzle zusammen und bringe das zum Einsatz, was mir gerade passend erscheint. Alkestis klingt eher archaisch, einfach, karg und rau, Orpheus eher neoromantisch.“

Seine Alkestis komponierte Genin 2015, den Orpheus zwei Jahre später, auf Initiative von Oksana Lyniv: „Sie schlug mir vor, Orpheus zu vertonen und ein Diptychon zu erstellen.“ Im Jahr 2023, in den Tagen vor der Uraufführung der beiden „Mini-Monoopern“, drängt sich Genin mehr denn je die Aktualität der zeitlos modernen Handlungen auf: „Dass sich Menschen so ändern und sich plötzlich von einer ganz anderen Seite zeigen. Dass Freunde keine Freunde mehr sind, zum Beispiel – das steckt darin. Oder dass sich Leute plötzlich nicht mehr kennen. Dass jemand, der dem Tod noch nicht begegnet ist, einen anderen, der genau das erlebt hat, nicht mehr verstehen kann. Das alles kommt jetzt stark hoch und schafft Verbindungen, die ich noch gar nicht vor Augen hatte, als ich die Werke schrieb. Orpheus versteht Eurydike nicht, er versteht nicht, was sie in der Unterwelt erlebt und erfahren hat. Und irgendwo spiegelt das natürlich die Situation der Ukraine. Die Leute hier verstehen nicht, was die anderen dort erlebt haben. Eurydike, die den Tod erlebt hat, befindet sich auf einer anderen Stufe des Daseins, sie kann nicht mehr Orpheus’ Frau sein. Er dagegen bleibt bei seiner Identität als Künstler und Sänger, aber er kann nicht nachvollziehen, was sie erlebt hat. Auch die Leute um Alkestis herum verstehen nicht, was sie opfert: Sie wählt den Freitod, um ihren Mann zu retten.“

Stimmen hören

Vor bald einem halben Jahrhundert schrieb auch die schottische Komponistin Thea Musgrave eine Art Monodram über den Orpheus-Mythos, eine „Vierzehn-Minuten-Oper“, wie das Stück genannt worden ist. Dieses Werk war ursprünglich für den Flötisten James Galway bestimmt, für ihn allein, denn Musgrave will uns vor Augen und Ohren führen, dass sich der Abstieg in die Unterwelt, in das Schattenreich der Toten (und in eine „verbotene“ Vergangenheit) nur in der Phantasie des mythischen Sängers abspiele, der vergeblich versucht, die verlorene Eurydike ins Leben zurückzuholen. Deshalb komponierte Musgrave die Urfassung, den Orfeo I, für Flöte und Tonband: Der Flötist steht allein auf der Bühne, im Wechselspiel mit sich selbst, unsichtbar umgeben von anderen Stimmen, die seine eigene vervielfältigen, da er zuvor die Musik für das Tonband mit verschiedensten Flöten aufgenommen hat. Diesen multiplen Orpheus übertrug Musgrave 1975 auf ein Ensemble aus Flöte und 15 Streichinstrumenten, die – ganz ähnlich wie später bei Genin – den „griechischen Chor“ repräsentieren. Musgrave charakterisiert ihre Musik als „dramatisch-abstrakt“, und in diesem zweifachen Sinn ist auch der Titel zu verstehen: Orfeo II. An Improvisation on a Theme. Einerseits entfacht sie ein Drama – in der Partitur finden sich sogar szenische Anweisungen: „Orfeo steht an den Ufern des Styx und klagt um Euridice … Orfeo hört ein fernes Echo von Euridice … Orfeo ist verzweifelt, er bestürmt den Charon, ihn über den Styx zu rudern.“ Andererseits entfaltet sie ein ungebundenes musikalisches Spiel, eröffnet den Instrumentalist:innen Freiräume für Improvisationen, setzt auf aleatorische Überraschungsmomente: auf eine Musik, die wie neugeboren aus jedem Augenblick entsteht und die sich doch an tönenden Ikonen der Musikgeschichte stößt, an Zitaten aus Christoph Willibald Glucks Orfeo von 1762. Aber mit diesen Anklängen neigt sich die Abstraktion wieder dem Drama zu. Oder dem inneren Monolog: Musgrave setzt die Fragmente aus Glucks Oper als „memory elements“ ein, um zu zeigen, dass die Erscheinungen, dass Eurydike, dass die Furien, die Schatten, nur Erinnerungen oder Beschwörungen sind und dass sich Orpheus unaufhaltsam von der Realität entfernt, hinab in die Unterwelt, in das Unterbewusstsein, die eigene, unentrinnbare Wirklichkeit jenseits der Wirklichkeit. Thea Musgrave, die in diesem Jahr ihren 95. Geburtstag feiern konnte, verwandelt den antiken Mythos in eine moderne Trauermusik und in eine Geisterstunde der verlorenen Liebe.

Wolfgang Stähr, geboren 1964 in Berlin, schreibt über Musik und Literatur. Er verfasste Buchbeiträge zur Bach- und Beethoven-Rezeption sowie über Haydn, Schubert, Bruckner und Mahler und publizierte Essays und Werkkommentare für die Festspiele in Salzburg, Grafenegg, Luzern, Würzburg und Dresden, Orchester wie die Berliner und die Münchner Philharmoniker, für Rundfunkanstalten, Schallplattengesellschaften, Konzert- und Opernhäuser.

The Artists

Oksana Lyniv

Conductor

Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv’s international career took off in 2004 with a third-prize win at the Bamberg Symphony’s Gustav Mahler Conducting Competition. After an engagement at the Odessa Opera House, she served as assistant to Music Director Kirill Petrenko at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich from 2013 to 2017 before taking over the position of Principal Conductor at the Graz Opera for three years. Since 2022, she has been Music Director at the Teatro Comunale in Bologna. As a guest conductor, she has led productions at Berlin’s Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Frankfurt Opera, Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Teatro dell’Opera in Rome, Vienna’s Theater an der Wien, and Stuttgart State Opera, among others. In 2021, she became the first female conductor in the history of the Bayreuth Festival when she made her debut leading a new production of Der fliegende Holländer. On the concert podium, she has conducted the Bavarian and Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestras, the Munich Philharmonic, the Staatskapelle Berlin, and many others. In addition to performing, Oksana Lyniv is passionately committed to the development of classical music culture in her home country and in 2016 founded both the LvivMozArt festival and the Youth Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine.

November 2023

Susan Zarrabi

Mezzo-Soprano

German-Iranian mezzo-soprano Susan Zarrabi completed her studies with Daniela Sindram at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in her hometown of Munich. She joined the ensemble of Berlin’s Komische Oper in 2022, following two seasons as a member in the company’s opera studio. Her roles there have included Dorabella in Così fan tutte, the Second Lady in Die Zauberflöte, Princess Clarice in Prokofiev’s The Love of Three Oranges, Arsamene in Handel’s Serse, and Tseitel in Fiddler on the Roof, among others. In April 2024, she will be heard as Cherubino in a new production of Le nozze di Figaro. Other appearances have taken her to Munich’s Bavarian State Opera, Staatstheater Augsburg, the Munich Radio Symphony conducted by Ulf Schirmer (Sara in Jonathan Dove’s Tobias and the Angel), the Cologne Philharmonie (Orlofsky in Die Fledermaus), Alte Oper Frankfurt, and Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie. Her concert repertoire includes works by Handel, Bach, Mendelssohn, and Mendelssohn. She has won particular acclaim as a recitalist, winning the Special Prize of the Wigmore Hall Song Competition last year. She was a member of the Lied Academy of the Heidelberger Frühling Festival led by Thomas Hampson and has performed at the Gustav Mahler Festival in Steinbach am Attersee, Austria, and (together with Thomas Hampson) at the Mahler Forum for Music and Society in Klagenfurt. She has appeared several times as part of the Pierre Boulez Saal’s Schubert Week.

November 2023

Christopher Ainslie

Countertenor

South African Christopher Ainslie has been acclaimed as one of today’s leading performers of the countertenor repertoire. In recent season, he was heard in the male title role of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice at Seattle Opera and as Oberon in Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Malmö Opera, Teatro Carlo Felice in Genoa, and the Royal Opera House in Muscat, Oman. He also made debuts at Dresden’s Sächsische Staatsoper (as Prince Go-Go in Calixto Bieito’s production of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre), Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris (David in Handel’s Saul, directed by Barrie Kosky), and at the Teatro Real in Madrid (Unulfo in Claus Guth’s new production of Rodelinda). Other guest appearances have taken him to the Handel Festival in Göttingen, English National Opera, Opéra national de Lorraine, Opéra de Massy, and Opéra de Lyon. In addition to his operatic performances, Christopher Ainslie has been heard with Les Musiciens du Louvre and Marc Minkowski, Les Arts Florissants and William Christie, the Nederlandse Bachvereniging, B’Rock, and the Philadelphia Orchestra, among others. In June 2024, he will make his debut at the Vienna Volksoper in John Adams’s The Gospel According to the Other Mary.

November 2023

Boulez Ensemble

Founded by Daniel Barenboim, the Boulez Ensemble has its artistic home in the Pierre Boulez Saal at the Barenboim-Said Akademie, where it made its first appearance in June 2015 at the building’s topping-out ceremony. This was followed in January 2017 by the international debut at Carnegie’s Zankel Hall in New York as part of a memorial concert for Pierre Boulez. Since the opening of the Pierre Boulez Saal in March 2017, the ensemble has presented its own concert series here, which has included collaborations with artists such as Zubin Mehta, Sir Antonio Pappano, Matthias Pintscher, Sir Simon Rattle, François-Xavier Roth, Lahav Shani, Jörg Widmann, Giedrė Šlekytė, Emmanuel Pahud, Mojca Erdmann, Christiane Karg, and Magdalena Kožená, among many others. As a flexible group not bound by a permanent roster of performers, the Boulez Ensemble consists of musicians primarily drawn from the ranks of the Staatskapelle Berlin and the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, as well as faculty and students of the Barenboim-Said Akademie and international guest artists who come together for each individual project. The ensemble’s artistic identity is expressed in its concert programs, which combine compositions from the Classical and Romantic repertoire with masterpieces of the 20th century and works by contemporary composers, while also juxtaposing duo and trio pieces with music for larger ensemble. The works of Pierre Boulez form a central part of the group’s repertoire. The ensemble also regularly presents world premieres of newly commissioned works, so far including compositions by Benjamin Attahir, Johannes Boris Borowski, Luca Francesconi, Matthias Pintscher, Aribert Reimann, Kareem Roustom, Vladimir Tarnopolski, and Jörg Widmann. The result of this programmatic approach is an inspiring combination of styles, in which the juxtaposition of diverse works opens up new listening perspectives—facilitating musical discovery and artistic dialogue that pay tribute to the spirit and memory of composer, conductor, and visionary Pierre Boulez.

November 2023