Katharina Bäuml Shawm and Musical Direction

Margaret Hunter Soprano

Birgit Bahr, Kohei Soda Alto Pommer

Annette Hils Bass Dulcian, Flute

Yosuke Kurihara Trombone

Mike Turnbull Percussion

Daniel Seminara Lute

Martina Fiedler Organ

Imogen Kogge Narrator

Program

Works by

Thoinot Arbeau

Jean Japart

Pierre Passereau

Antoine Busnoys

Adrian Le Roy

Claudin de Sermisy

Antoine de Févin

Guillaume Le Herteur

and Traditional Breton Chansons and Dances

Spoken Text in German

Une Femme d’esprit

The Life of Anne of Brittany (1477–1514)

Patroness of Arts and Sciences

Thoinot Arbeau (1520–1595)

Triory de Bretagne

Breton Chanson / Jean Japart (c. 1450–after 1500)

C’etait Anne de Bretagne / Il est de bonne heure né

Long-Distance Marriage with Emperor Maximilian I

Pierre Passereau (1490–after 1547)

Il est bel e bon

Antoine Busnoys (c. 1430–1492)

Fortune espérée

Anonymus (16th century)

La Gamba (instrumental)

Marriage and Life at Court with King Charles VIII

Thoinot Arbeau

Belle qui tiens ma vie

Adrian Le Roy (c. 1520–1598)

Si j’ayme ou non, je n’en dis rien

Anne and her Court Ladies

Claudin de Sermisy (c. 1490–1562)

Jouissance vous donneray

Thoinot Arbeau

Basse Danse appellée Jouissance vous donneray (instrumental)

Antoine de Févin (c. 1470?–1511/12)

Introitus from the Missa Pro fidelibus defunctoris

Return to Brittany

Breton Chanson

Sainte-Anne, Ô bonne mère

Anonymus / Guillaume Le Herteur (fl. 1530–49)

Basse Danse Aliot Nouvelle / Mirelaridon

Intermission

Anne and the Printing Press

Claudin de Sermisy

Tant que vivray

Anonymus

Il est de bonne heure né (c. 1480)

Costanzo Festa (c. 1480/90–after 1540)

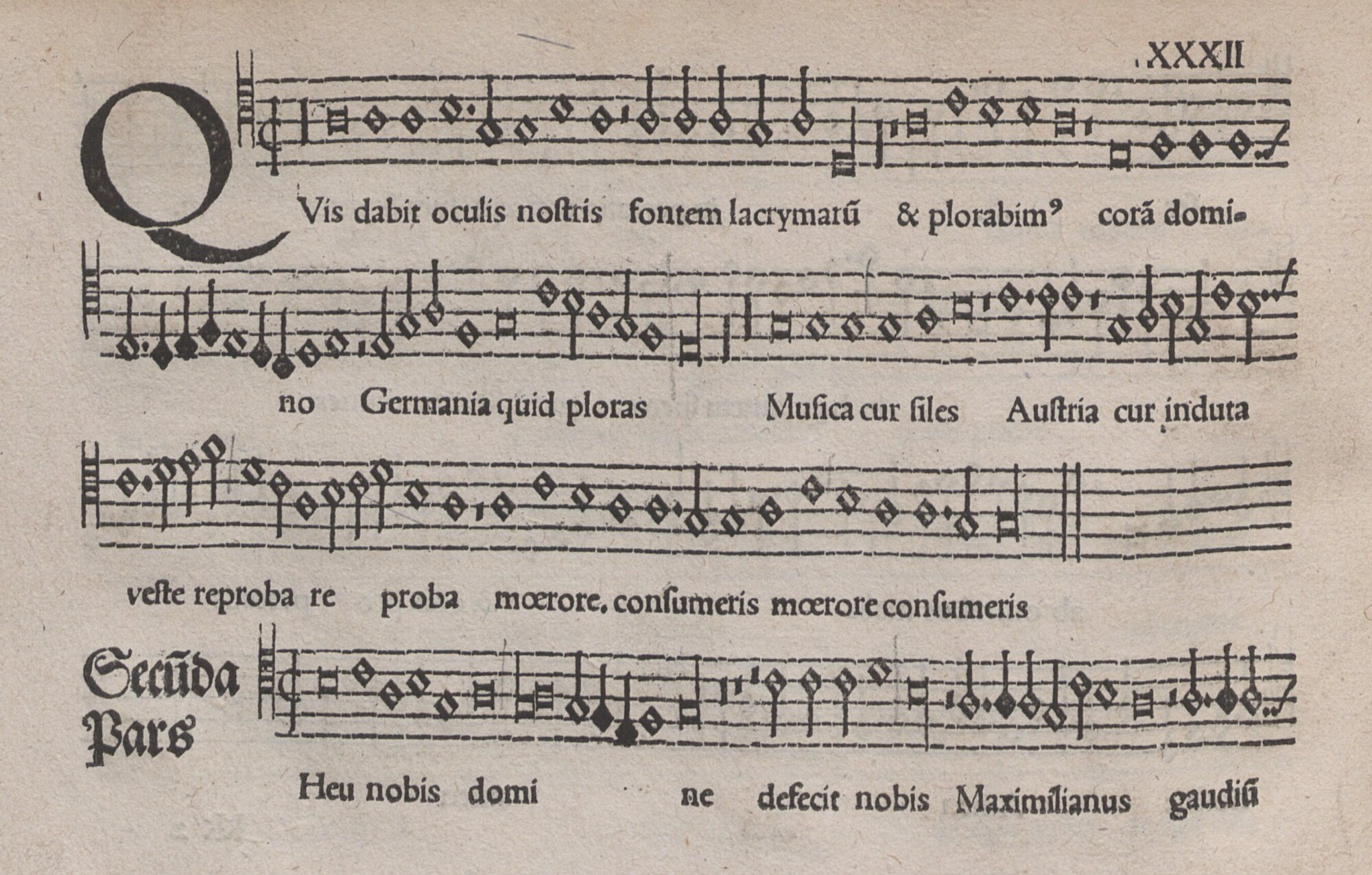

Qui dabit oculis nostris

Anne and Death

Pierre Moulu

Tant que vivray

Anonymus (1484–c. 1540)

Une jeune filette de noble coeur

At the Court of Louis XII

Anonymus / Gilles Binchois (c. 1400–1460?)

Basse Danse Mon Désir / Filles à marier

Jacques Arcadelt (1507–1568)

Margot labourez les vignes

Anonymus

Basse Danse La Brosse / Tourdion (instrumental)

Renaissance Woman

Breton Chanson / Guillaume Le Herteur

C’etait Anne de Bretagne / Mirelaridon

Court poet Jean Marot presents Anne of Brittany with his book Le Voyage de Gênes about the French campaign against Genoa in 1507, miniature by Jean Bourdichon (1510–20)

(Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Une Femme d’esprit

Her heart belonged to Brittany, that formerly proud and independent territory in the Northwest of France. That is where she was born, where she grew up and enjoyed great popularity—Duchess Anne de Bretagne. She died young at the age of 37, was married to three high-ranking regents, and was an outstanding patroness of the arts at her court.

Essay by Bernhard Schrammek

Une Femme d’esprit

The Life and Times of Anne de Bretagne

Bernhard Schrammek

Her heart belonged to Brittany, that formerly proud and independent territory in the Northwest of France. That is where she was born, where she grew up and enjoyed great popularity—Duchess Anne de Bretagne, who went on to become Queen of France and managed to pragmatically tolerate the integration of her homeland into France’s central power. She died young at the age of 37, was married to three high-ranking regents, and was an outstanding patroness of the arts at her court. Her grave can be found at the Cathedral of Saint-Denis in Paris, but her heart—as she had directed in her will—rests in Nantes, in Brittany, enclosed in a golden capsule.

A Duchess and a Queen

There, Anne was born in 1477 as the daughter of Duke Francis II. From earliest childhood, she was a first-hand witness to her homeland’s struggle to maintain its independence from the dominant French central state. Violent struggles were an everyday occurrence during these years, as the French King Charles VIII strove to expand his territory with force and brutality. When Duke Francis II died in 1488, Anne, not even twelve years of age, became the successor to the throne and took on the responsibility for Brittany in this unequal struggle. She and her advisors hoped for help from Maximilian, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Germany, which was why Anne entered into marriage with him in 1490. But the spouses never met, much less touched each other, for the marriage was concluded in the absence of the Emperor, who was on the battlefield far from Brittany. Officially, this made Anne the Archduchess of Austria—yet the union had a fatal formal flaw: the French King would have had to consent to the marriage, but had not been asked. As a consequence, his troops invaded Brittany once again, taking the fortress in Nantes and the residence in Rennes. The Emperor did nothing to help her, so that Anne no longer felt bound by her remote marriage.

To prevent bloodshed among her compatriots, she entered into negotiations with the French side, agreeing to a marriage with 21-year-old Charles VIII, which would seal the political alliance. A voluminous contract was crafted, placing Brittany under the administration of the French crown. The existing marriages of Anne (to Emperor Maximilian) and Charles VIII (to one of the Emperor’s daughters, of all people) were annulled by Papal authority, albeit with some delay. At the age of 15, then, Anne was Queen of France and had negotiated a peace treaty for her people.

The young royal couple went on to reside mostly at the Château d’Amboise on the Loire. During the following years, Anne gave birth to six children, none of whom survived infancy and childhood. And fate was to deliver an even harder blow: in April 1498, Charles himself died after an accident in his own castle. Twenty-one years of age, Anne was a widow without heirs. The marriage contract stipulated two consequences: Brittany was once again placed under Anne’s administration, while she herself was obliged to marry the successor to the throne.

Anne acquiesced to these rules and entered into her third marriage in 1499 with the new King Louis XII, the former Duke of Orléans and the cousin of his predecessor. This, again, required the annulment of a marriage, for Louis was already married; the Borgia Pope Alexander VI took care of the matter without fuss. The Château de Blois, also located on the Loire, was chosen as the main residence of the new royal couple. Anne gave birth to five more children through 1512; her eldest daughter Claude, in turn, later became Queen of France as well by marrying Francis I.

Her time as a ruler put an enormous strain on Anne, not only because of her continuous pregnancies, but also due to numerous journeys and dealing with political crises and other campaigns France was involved in. During the winter of 1513–4, she fell seriously ill and failed to recover. Anne de Bretagne died at the Château de Blois in January 1514.

A Passion for Education and the Arts

Despite her self-sacrificing life that was determined by political decisions, Anne was a passionate patron of the arts and education and made it her special mission to support women. Both in Amboise and Blois, she assembled a large number of ladies-in-waiting—some single, some married—and championed their comprehensive and in-depth education, paying all expenses and arranging several marriages. In some cases, Anne—and thereby, the French court—even assumed the considerable expenses of their dowry.

Anne de Bretagne was not only open-minded about the arts, but supported painters, sculptors, poets, writers, and musicians wherever she could. She was particularly interested in printing. As befitted this extraordinary sovereign’s character, she recognized the ground-breaking potential of this new technology, then still in its infancy, and made personal efforts to increase its reputation and effect—among other initiatives, she passed a law in 1513 granting printers exemption from tariffs and tax relief.

Music at Court

Music was a valued art, of course, in the life of Anne de Bretagne’s expansive court. There were two royal orchestras in her immediate surroundings: one was assigned to the King, the other to her, the Queen, personally. These ensembles were responsible for public representation of the rulers at church services, festivities, and receptions, but also for their private entertainment in the royal chambers.

The scarcity of musical sources makes it difficult to ascertain whether individual compositions were played during Anne’s reign. The only two with a proven connection are the lamentation Fiere atropos mauldicte by Pierre Moulu and the motet Quis dabit oculis nostris by Costanzo Festa, as both were written on the occasion of Anne’s death. It seems likely, however, that the repertoire of the court orchestras would have included works by the most important French composers of the 15th and early 16th centuries. This circle included Antoine de Fevin and Claudin de Sermisy, for example, both members of the royal court orchestra themselves, but also Pierre de la Rue and Gilles Binchois, who were long employed by the court of Burgundy, and certainly also the composer Jean Japart, who lived mainly in Italy.

In addition to music, dance was a central pastime at court. Thoinot Arbeau offers important evidence for the repertoire of the early 16th century in his famous book of dances, published in 1588, in which he included many dance melodies written significantly earlier. Other pieces on Capella de la Torre’s program were composed by Claude Gervaise, a viol player who probably lived in Paris. Last but not least, Anne also supported patriotic causes in Britanny—so we may safely assume that Breton music with its traditional songs played an important role at her court.

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

Dr. Bernhard Schrammek, born in 1972, is a freelance musicologist and writer based in Berlin. He hosts radio programs for rbb, MDR, and Deutschlandfunk Kultur, writes program notes, and curates concert programs. He has been artistic director of the SPAM – Spandau macht Alte Musik festival since 2023.

Costanzo Festas' Quis dabit oculis nostris was composed on the occasion of Anne de Bretagne's death in 1514. When Anne's first husband, Emperor Maximilian I, died a few years later, composer Ludwig Senfl borrowed Festas' funeral music and inserted Maximilian's name into the text. Edition printed in Nuremberg, 1538.

(Bavarian State Library Munich)

Music as a Distant Mirror

Katharina Bäuml talks about her fascination with Anne de Bretagne, the inspiration for this program, and the musical challenges behind it.

Music as a Distant Mirror

A Conversation with Katharina Bäuml

Anne de Bretagne was an unusual woman for her time. What do you imagine her to have been like?

What I find fascinating about Anne is that her role seems so clearly defined—even from today’s point of view. For all we know, she was a wise and far-sighted sovereign who was also very interested in education, culture, and music. I find it especially remarkable that a woman from this era should have left such impressive traces. When you look at her family history, on the other hand, it can make you quite sad: she was married three times to famous rulers and was frequently pregnant but lost most of her children. Anne had to make all these personal sacrifices for the sake of political circumstances and to take responsibility for her people. As a woman, she placed not only her professional, but also her private identity at the service of reasons of state. This makes her one of the few strong women of early modern times—alongside more famous ones such as Elizabeth I, Caterina de Medici, or Isabella of Castile—and there’s a lot to tell about her even from a modern perspective.

What do we know specifically about the culture at her court?

The sources are quite rich, so we know more than a thing or two about the cultural customs at Anne’s court. For example, it was not unusual for noblewomen to receive a universal education there, and that included musical activities too. All this contributed to the rich cultural life that was soon considered exemplary throughout Europe. This also includes the beginnings of printing—among other things, Anne de Bretagne supported the first printing of Christine de Pizan’s Le Trésor de la cité des dames.

What guided you in assembling the program for this concert?

With Capella de la Torre, we have long followed the principle of programs focused on the history of ideas or the lives of specific people. We’ve already devoted an entire album to Isabella of Castile. When we now turn to the life and times of Anne de Bretagne, the focus is not primarily on chronology or retelling her life story, but on adopting an artistic perspective. We’d like to look more at the big picture, so that the combination of texts and specific pieces of music sparks the listener’s imagination and creates the panorama of an era. The point is to train our contemporary gaze on a famous female figure and perhaps to discover things that are hidden between the lines.

Capella de la Torre performs in a special formation, with many wind instruments. How does that fit with music at the court of Anne de Bretagne?

I think that the sonic colors especially of the winds act as a kind of distant mirror, bringing the Renaissance period to life, visibly and audibly. When we then add voices, lute, organ, and percussion, we have a sonic panorama that gives a particularly vivid image of the era and is also the hallmark of our own interpretations over the past 20 years.

I suspect that you had to arrange many of the pieces to fit the requirements of the ensemble. How do you go about this?

I always try to arrange the works so that the result is as authentic as possible and works well for the instrument and the voice, but also does justice to the basic idea of the original. I have found that it makes sense to experiment a lot at the beginning. For example, in a polyphonic composition, it’s possible to focus on only one or two selected voices for a while and then revert to full polyphony, or to alternate between vocal and instrumental passages. Then I try to adapt this to the program’s dramaturgy—of course also with an eye to presenting as many contrasts as possible to the audience.

Do you have favorite pieces in this program?

I really like that a female ruler also seems to embody the lesser-known music of a certain region, Brittany in this case—not least because the bombarde, an instrument still used today in traditional Breton music, is a relative of my own instrument, the shawm. That’s another reason our instruments are well suited to this region. Making such a regional color shine in the context of European Renaissance music is something I find particularly attractive. It’s certainly a special aspect of this program.

Interview: Bernhard Schrammek

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

The Artists

Katharina Bäuml

Shawn and Musical Director

Munich-born Katharina Bäuml first studied modern oboe and later specialized in Baroque oboe and historical reed instruments at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. Her main interest is in wind music from the 14th to the 17th centuries, but she is also passionate about contemporary repertoire and has performed numerous new works with accordionist Margit Kern as Duo Mixtura, including at the Ultraschall festival in Berlin. In addition to her work with Capella de la Torre, Katharina Bäuml is artistic director of the Musica Ahuse concert series in Auhausen, Bavaria, and of Renaissancemusik an Elbe und Weser in Lower Saxony, as well as the Sounding Collections festival in Berlin. Since 2020, she has been curating the online platform Studio4Culture, which creates new interactive concert formats and educational programs.

December 2025

Capella de la Torre

Founded in 2005 by oboist and shawm player Katharina Bäuml, Capella de la Torre is among today’s leading ensembles for wind music from the early modern era. The name “de la Torre” refers both to 14th-century Spanish composer Francisco de la Torre and to the historical performance practice of playing wind music on towers and balconies. Through work with period sources and texts, the ensemble’s programs are always informed by the latest historical and musicological research. The musicians also reach out to young audiences in various initiatives. For its me than 30 recordings, Capella de la Torre has been honored with numerous awards, including the 2016 ECHO Klassik for Best Ensemble and, most recently, the 2023 OPUS Klassik for their album Monteverdi: Memories.

December 2025