Christian Tetzlaff Violin

Leif Ove Andsnes Piano

Program

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major K. 526

Maurice Ravel

Sonata for Violin and Piano in G major

Johannes Brahms

Sonata for Violin and Piano in D minor Op. 108

Donghoon Shin

Winter Sonata

for Violin and Piano

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major K. 526 (1787)

I. Molto allegro

II. Andante

III. Presto

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Sonata for Violin and Piano in G major (1923–7)

I. Allegretto

II. Blues. Moderato

III. Perpetuum mobile. Allegro

Intermission

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Sonata for Violin and Piano in D minor Op. 108 (1886–8)

I. Allegro

II. Adagio

III. Un poco presto e con sentimento

IV. Presto agitato

Donghoon Shin (*1983)

Winter Sonata

for Violin and Piano (2025)

Encore

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

from the Violin Sonata in E-flat major K. 481

II. Adagio

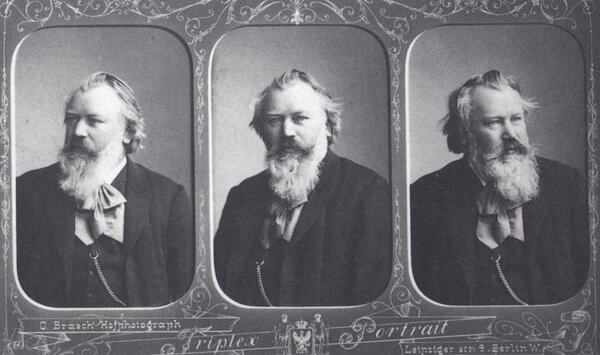

Johannes Brahms, 1889

Essays in Sonata Form

Of many formal structures that Western composers have devised to shape their musical thoughts, none has been more influential than sonata form. Although it has undergone many permutations since the 18th century, its basic idea has remained unchanged. The four sonatas on tonight’s program, each composed in a different century, are variously indebted to this legacy of the Classical era.

Program Note by Harry Haskell

Essays in Sonata Form

Works for Violin and Piano

Harry Haskell

Of many formal structures that Western composers have devised to shape their musical thoughts, none has been more influential than sonata form. Although it has undergone many permutations since the 18th century, its basic idea has remained unchanged: it is built on the contrast between two themes, which are first presented, then developed, and ultimately recapitulated, resulting in a musical architecture that is more or less pleasingly symmetrical. The four sonatas on tonight’s program, each composed in a different century, are variously indebted to this legacy of the Classical era. South Korean composer Donghoon Shin explains its enduring appeal for him and his contemporaries this way: “Sonata form’s essence lies in its experimentation with harmonic direction and momentum, and this is the reason why such an old musical form, which has been inherited and developed by countless composers, remains valid to this day.”

Mozartean Bravura

Mozart’s legendary virtuosity on the piano is amply attested. Less well known is that he was also a child prodigy on the violin, the instrument on which his father earned his reputation. (The author of a famous textbook on violin playing, Leopold Mozart was a violinist in the orchestra of the archbishop of Salzburg.) Young Wolfgang seems to have learned his way around the violin by osmosis. A family friend told of playing string trios with the untutored seven-year-old wunderkind: they started out doubling the second-violin part, but the older man “soon noticed with astonishment that [he] was quite superfluous” and bowed out. Although Leopold frequently berated his son for neglecting the violin, by age 13 Wolfgang was playing alongside his father in the court orchestra, and three years later he was promoted to concertmaster.

Despite Mozart’s brash self-confidence—in one of his cockier moments he boasted that he was equal to “the finest fiddler in all Europe”—he never felt as comfortable playing string instruments as he did the keyboard. The Sonata in A major K. 526 is listed under the date August 24, 1787, in the composer’s catalogue of his works. It is one of three violin sonatas that he wrote in the mid-1780s, including the brilliant Sonata in B-flat major K. 454, composed for the Italian virtuosa Regina Strinasacchi. The tonal ideal that Mozart sought in these three “late Viennese” sonatas is reflected in Leopold’s description of Strinasacchi’s performance: “No one can play an adagio with more feeling than she does. Her whole heart and soul are in the melody that she is playing, and her tone is as beautiful as it is powerful.”

Longer and more elaborately worked out than Mozart’s earlier sonatas, the bravura A-major Sonata makes virtuosic demands on both violinist and pianist. The spitfire passagework of the fast movements and the intricate figurations of the central Andante far exceed the capacity of most amateur players. After a giddy, metrically ambiguous opening, the Molto allegro eventually settles into an easygoing 6/8 groove, the two instruments taking turns introducing and developing the thematic material. At the beginning of the D-major slow movement, the piano’s striding octaves provide a platform for snatches of melody in the violin. Then the roles are reversed, as the violin takes over the music first played by the pianist’s right hand. By the time we reach the final Presto, a cut-time rondo that flies like the wind, any hierarchical distinction between the instruments is meaningless.

A Soupçon of Jazz

Thirteen years younger than Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel made his mark in Paris at the turn of the 20th century with a group of brilliantly crafted piano pieces, including Pavane pour une infante défunte and Jeux d’eau, and the masterful String Quartet. Over the ensuing decades he refined his art, ruthlessly pruning away superfluous notes and gestures in search of the “definitive clarity” that was his professed ideal. By the time Debussy died in 1918, Ravel was widely hailed as the new standard-bearer for French music. He shared with his predecessor a poetic sensibility and a fondness for sensuous, impressionistic timbres and textures. But unlike the mold-breaking Debussy, Ravel was at heart a classicist. Many of his works evoke composers and styles of the past, even as they incorporate ultramodern harmonies and compositional styles.

The Sonata for Violin and Cello of 1920–2 was a turning point on Ravel’s stylistic journey. Both the linear transparency of the part writing and the cool austerity of the harmonic language signaled a departure from the luxuriant impressionism that had characterized many of his earlier works. He continued along the same path in the Sonata for Violin and Piano in G major, which occupied him on and off between 1923 and 1927. It is one of several jazz-influenced works that Ravel wrote after hearing an African American jazz band play in Paris; he recalled being equally impressed by the ensemble’s free-spirited music and its “frightening virtuosity.” Composed in the idyllic seclusion of Ravel’s country retreat, Montfort-l’Amaury, the Violin Sonata had its premiere in Paris on May 30, 1927, with George Enescu on the violin and the composer at the piano.

Oddly enough, Ravel considered the violin and piano “essentially incompatible” and took pains to highlight their individuality and independence. The opening Allegretto sets the tone with its spare, diaphanous textures, impetuous lyricism, and quirky melodic twists and turns (reminiscent, Ravel said, of barnyard sounds). The easy swing and bluesy harmonies of the second movement evoke the classic blues of W. C. Handy in a playfully refined, drawing-room manner. Listen for the fleeting allusions to Gershwin’s newly minted Rhapsody in Blue—a work that Ravel greatly admired—both here and in the finale. The latter spins along like a perpetual-motion machine, the violin busy and slightly manic, the piano delicate and luminous.

Drama and Passion

Johannes Brahms first met the Hungarian violinist-composer Joseph Joachim in the spring of 1853. Although only two years older than Brahms, the concertmaster of the Hanover court orchestra was already an international celebrity. “As an artist I really have no greater wish than to have more talent so that I can learn still more from such a friend,” Brahms wrote in the first flush of their friendship. Joachim’s practical knowledge of both violin and orchestra made him an invaluable sounding board. Brahms turned to him for advice throughout his life, especially in the decade between 1878 and 1888, when he wrote his Violin Concerto in D major and three violin sonatas.

The third sonata, in the “dark” key of D minor, is weightier and more overtly dramatic than its predecessors in G major and A major. Its dedicatee, Hans von Bülow, cut a notably titanic figure at the keyboard as well as on the podium, and the work’s impassioned, virtuosic character may well bear his stamp as well as Joachim’s. The music may also allude to Brahms’s long-simmering love for pianist Clara Schumann. Upon receiving the score, she wrote coquettishly to the 55-year-old composer that the third movement reminded her of “a beautiful girl sweetly frolicking with her lover—then suddenly in the middle of it all, a flash of deep passion, only to make way for sweet dalliance once more.”

Whatever feelings it expresses, the D-minor Sonata is unquestionably infused with passion. From the first bars of the opening Allegro, the staggered eighth notes and recurrent dynamic swellings bespeak the music’s underlying turbulence. The mood of barely contained wildness is briefly dispelled in the majestic D-major Adagio—despite its brevity, one of Brahms’s most concentratedly intense slow movements. This leads to an ethereal scherzo in F-sharp minor, whose opening theme returns at the end in a deceptively tranquil reminiscence. (Schumann likened this delicate and devilishly difficult passage to walking on eggshells.) In the final Presto agitato, the sonata’s pent-up energy bursts forth in a high-spirited romp in 6/8 meter, charged with stabbing accents and syncopations.

Winter to Spring

After receiving his early musical training in Seoul, Donghoon Shin moved to London in his early 30s to pursue studies with George Benjamin, a protégé of Olivier Messiaen. Like Benjamin, Shin shares the French composer’s penchant for subtle coloristic timbres and complex rhythmic structures. A case in point is the Winter Sonata, which Christian Tetzlaff and Leif-Ove Andsnes premiered last June in Heimbach. It follows hard on the heels of two major symphonic works that brought the 42-year-old Korean composer to the attention of Berlin audiences: the viola concerto Threadsuns, which the Berlin Philharmonic premiered last year, and the 2022 cello concerto Nachtergebung, introduced by the orchestra’s Karajan Academy under the baton of Kirill Petrenko.

Cast in a single movement lasting some 17 minutes, the Winter Sonata takes its cue from Beethoven’s highly dramatized concept of sonata form. The energizing contrast, in this case, is not only between two themes—which Shin labels “winter” and “spring”—but also between tonality and atonality. (It is no coincidence that the lyrical “spring” theme, which emerges from the dense, turbid harmonies of the sonata’s opening section, shares the tonality of F major with Beethoven’s “Spring” Sonata for Violin and Piano.) What Shin describes as “a twisted, almost mocking (!) parody of Beethoven,” in the sonata’s middle development section, leads to “an almost frantically hopeful, even manic” recapitulation and a final affirmation of the sonata’s elusive C-major/minor tonality.

Shin explains that “Winter Sonata was originally only a working title. I attributed it to the piece as a joke while writing during the dark London winter. However, as the idea of the harmonic contrast between the winter and spring themes and the atonality-tonality context developed, I realized it was a title that truly represented the work. Composers are also creatures of their times. The gloomy winter weather, and the horrific news I was hearing reported at the time, deeply influenced me as I composed the piece. Outside my studio window stands a big sycamore tree. A few years ago, during the spring of the pandemic, a pair of magpies built a large nest in its branches. Since then, each year, different magpies have come and repaired the old nest to create their own new home. While writing this piece, I waited for spring and for the magpies to appear. And now as the piece is completed, the magpies have returned once again. It is often in such small things that we find hope.”

A former performing arts editor for Yale University Press, Harry Haskell is a program annotator for Carnegie Hall in New York, the Brighton Festival in England, and other venues, and the author of several books, including The Early Music Revival: A History, winner of the 2014 Prix des Muses awarded by the Fondation Singer-Polignac.

Donghoon Shin (© Lee Tae Kyung)

Zwiegespräche

Zum Saisonauftakt im Pierre Boulez Saal interpretieren Christian Tetzlaff und Leif Ove Andsnes Sonaten aus vier Jahrhunderten von Mozart bis zur erst 2025 uraufgeführten Winter Sonata des südkoreanischen Komponisten Donghoon Shin.

Essay von Kerstin Schüssler-Bach

Zwiegespräche

Sonaten für Violine und Klavier von Mozart, Ravel, Brahms und Shin

Kerstin Schüssler-Bach

In die Einsamkeit entrückt

Mehr als zwei Dutzend Violinsonaten hat Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart komponiert – beginnend schon in seinem sechsten Lebensjahr. Dass er auch als Interpret mit der Geige aufs Engste vertraut war, betonte sein Vater Leopold, Verfasser einer berühmten Violinschule: „Du weist selbst nicht wie gut du Violin spielst, wenn du nur dir Ehre geben und mit Figur, Herzhaftigkeit, und Geist spielen willst.“ Die A-Dur-Sonate KV 526, mit der Christian Tetzlaff und Leif Ove Andsnes ihr heutiges Programm – und damit die Saison im Pierre Boulez Saal – eröffnen, ist die letzte der drei großen „Wiener Sonaten“ und Mozarts eigentliches Gipfelwerk in dieser Gattung. In seinem eigenhändigen Werkverzeichnis hatte er diese „Klavier-Sonate mit Begleitung einer Violin“ auf den 24. August 1787 datiert – zwei Wochen nach der Serenade „Eine kleine Nachtmusik“ und zwei Monate vor der Premiere des Don Giovanni. Die unmittelbare zeitliche Nachbarschaft dieser äußerst prominenten Kompositionen macht es überflüssig zu betonen, dass auch dieses Werk ein reifes Mozart-Wunder ist: in vollkommener Balance der beiden Instrumente, von perfekten Proportionen, geistreichem Spiel, tiefem Ausdruck und nicht zuletzt virtuoser Musizierlust.

Die Sonate entstand auf Anregung des Verleger-Freundes Franz Anton Hoffmeister, der sie schon einen Monat später veröffentlichte und gut verkaufte. Dennoch ist sie weder ein Gelegenheitswerk noch eine reine Brotarbeit: Eng miteinander verwoben sind die beiden Instrumente im munteren Sechsachtelthema des Kopfsatzes, dessen vorgebliche Glätte durch einige rhythmische Stolpersteine gegen den Strich gebürstet wird. Die sorgfältige kontrapunktische Arbeit einschließlich kleiner Kanons verrät die Auseinandersetzung mit den barocken Meistern.

Das an zweiter Stelle stehende Andante verzichtet auf alle Äußerlichkeiten. „Es ist, als legte Mozart hier plötzlich das glänzende Gewand des Virtuosen ab, in das er sich damals nur noch mit Unlust hineinzwängte, und finge, in die Einsamkeit entrückt, für sich zu musizieren an“, schrieb schon Hermann Abert vor mehr als 100 Jahren in seiner Mozart-Biografie. Die strenge Oktavverdoppelung im Klavier im ruhig schreitenden Achtelthema und die zarten Verzierungen der Violine bieten vergleichsweise karges musikalisches Material. Plötzliche Dur-Moll-Wechsel, spannungsvolle Synkopen und kühne harmonische Rückungen erweitern das Ausdrucksspektrum. Leopold Mozart war im Mai des Jahres gestorben – womöglich ist der innige, aber auch durch „mühevolles Suchen und Wandern“ (Abert) geprägte Satz eine Verbeugung vor dem Übervater.

Dem Thema des Schlussrondos ist tatsächlich eine Totenehrung eingeschrieben: Der Mozartforscher Georges de Saint-Foix erkannte darin das Zitat eines Klaviertrios von Carl Friedrich Abel. Der zwei Monate zuvor verstorbene Musiker war ein Förderer des jungen Mozart auf dessen Reise nach London gewesen. In diesem dahinstürmenden Presto können beide Instrumente wieder ihre virtuosen Möglichkeiten zeigen. Das Skalenmotiv im Klavier wird durch launige Synkopen der Violine konterkariert, später vertauschen sich die Rollen. Aber auch hier finden sich kleine Eintrübungen und Schatten.

Lyrischer Glanz und Jazz-Anklänge

Maurice Ravels Violinsonate benötigte einige Jahre des Reifens: Der Komponist brach die 1923 begonnene Arbeit bald weder ab. „Ich habe [die Sonate] beiseite gelegt… meine Depressionen sind schlimmer als je zuvor“, bekannte er 1924. Zudem haderte er mit den „im Wesentlichen unvereinbaren Instrumenten“. Erst drei Jahre später wurde das Werk vollendet – nicht zuletzt dank praktischer äußerer Umstände, denn die Uraufführung war für Mai 1927 in der Pariser Salle Érard mit dem bekannten Geiger und Komponisten George Enescu und Ravel selbst am Klavier angekündigt. Der elfjährige Yehudi Menuhin, Schüler Enescus, wurde Zeuge dieser eiligen Fertigstellung und erinnerte sich in seinen Memoiren, wie seine Unterrichtsstunde unterbrochen wurde: „Plötzlich stürzte Maurice Ravel herein. Die Tinte auf seiner Sonate für Violine und Klavier war noch nicht trocken, aber sein Verleger Durand wollte sie sofort hören. Enescu, stets Kavalier, bat höflich um Entschuldigung und spielte mit Ravel das komplizierte Werk vom Blatt.“ Für die sofortige Wiederholung legte Enescu gar „die Noten weg und spielte es aus dem Gedächtnis noch einmal“.

Der zarte melodische Faden des eröffnenden Allegretto wird von der rechten Hand des Klaviers zur Violine weitergereicht und von dieser fortgesponnen. Sparsam, aber wirkungsvoll breitet sich lyrischer Glanz aus, während kurze Figuren im Klavierbass und flirrende Tremoli der Violine leichte Irritationen einbringen. Im „Blues“ überschriebenen zweiten Satz reflektiert Ravel seine Begegnung mit dem Jazz, dem er begeistert in den Nachtclubs von Paris lauschte. Die Violine imitiert mit gezupften Akkorden ein Banjo und lässt dann lockere Portamenti und Synkopen erklingen, vom Klavier in Honky-Tonk-Manier begleitet. Das abschließende Perpetuum mobile – es ersetzt das ursprüngliche, von Ravel verworfene Finale – nimmt rasch rasante Fahrt auf. Die rhythmische Vitalität steigert sich unter Anklängen an die vorangegangenen Sätze in einen schwindelerregenden Taumel.

Symphonische Dimensionen

Nachdem er einige „Sonaten für Violine und Clavier“ aus der Jugendzeit vernichtet hatte, wandte sich Johannes Brahms erst in späten Jahren wieder der Violinsonate zu – von seinem Beitrag zum Gemeinschaftswerk der „F.A.E.-Sonate“ abgesehen. Im musikalisch ertragreichen Sommer am Thuner See komponierte er 1886 seine Zweite Violinsonate und begann die Nr. 3 in d-moll, die allerdings erst zwei Jahre später fertiggestellt wurde. Anders als in den beiden Vorgängerwerken verzichtet Brahms in seiner letzten Violinsonate auf Anklänge an sein Liedschaffen. Ihr raumgreifender Klavierpart und die dramatische Anlage verleihen ihr ebenso wie die viersätzige Form fast symphonische Dimensionen. Womöglich auch deshalb hat Brahms sie dem Dirigenten Hans von Bülow gewidmet, der sich mit der Meininger Hofkapelle als führender Interpret Brahms’scher Symphonik bewiesen hatte. Richard Specht brachte in seiner 1928 erschienenen Biografie des Komponisten den nervös-genialischen Charakter des Widmungsträgers mit der d-moll-Sonate in Verbindung – „in ihrer unsteten Erregtheit, ihren fieberischen Visionen und ihren nur mühsam beruhigten Spannungen“.

Erste Empfängerin des neuen Werks war im Oktober 1888 die befreundete Pianistin Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, die es sogleich zusammen mit der Geigerin Amanda Röntgen in einer Leseprobe durchspielte: „Wie flogen die Augen von Takt zu Takt, wie wuchs Eifer und Lust von Seite zu Seite, wie begrüßten wir eine Schönheit nach der andern!“ Über mehrere Briefe hielt Herzogenbergs Enthusiasmus an, den Brahms wie üblich knorrig kommentierte und herunterspielte, obwohl er manche ihrer Änderungsvorschläge aufgriff.

Danach ging die Kopie an Clara Schumann, die die Novität „doch der zweiten“ Sonate vorzog, wie sie zufrieden vermerkte. Der öffentlichen Uraufführung im Dezember 1888 in Budapest mit dem Komponisten am Klavier und dem ungarischen Geiger Jenő Hubay gingen intensive Proben voraus. Hubay erinnerte sich: „Da fing er an zu feilen und änderte, verbesserte, bis endlich das entstand, was ihm in seinem Geiste vorschwebte.“

Die besondere Einheitlichkeit der Sonate, die auch Elisabeth von Herzogenberg begeisterte („die vier Sätze sind wirklich Glieder einer Familie“), speist sich nicht nur aus der für Brahms typischen motivischen Geschlossenheit, sondern auch aus einem durchgehenden dramatischen, ja leidenschaftlichen Atem. Den verhaltenen Schwung des Kopfsatzes bremst in der Durchführung ein langer Orgelpunkt aus: Das Klavier scheint auf der Dominante A unerbittliche Paukenschläge zu imitieren – ein ebenfalls in Brahms‘ Orchestermusik verwendeter Effekt. Die beiden Mittelsätze prägen in konzentrierter Form einen ganz eigenen Charakter aus: das innige Adagio in seiner „Kontinuität der Empfindung“ und das grimmige Kapriolen schlagende Scherzo „in seiner atemlosen Beweglichkeit – wir lachten wirklich vor Lust bei diesem Satz“ (Herzogenberg). Mit fast ungezügelter Wildheit stürmt das Finale in Beethoven’schem Furor los. Ein hymnischer Choral greift einen Gestus auf, den Brahms ebenfalls in seinen Orchesterwerken zu feierlicher Geltung brachte.

Kontrast der Jahreszeiten

Er sieht sich bewusst als Komponist, der das klassisch-romantische Erbe ins Heute transferiert: Donghoon Shin bringt in seiner Musiksprache eine vielfältige Palette der Emotionen und Haltungen ein. Geboren in Südkorea, studierte er bei Sukhi Kang, der auch Unsuk Chin unterrichtete. 2014 übersiedelte er nach London, um seine Ausbildung bei Julian Anderson fortzusetzen; ein weiterer wichtiger Mentor ist George Benjamin. Mit Auftragswerken u.a. der Berliner Philharmoniker, des London Symphony Orchestra und des Los Angeles Philharmonic hat sich Shin inzwischen auf internationalem Spitzenniveau etabliert.

Winter Sonata wurde Christian Tetzlaff und Leif Ove Andsnes auf den Leib geschrieben und von beiden Künstlern beim diesjährigen Kammermusikfestival „Spannungen“ in Heimbach zur Uraufführung gebracht. Das 17-minütige Werk vereint höchste Virtuosität, lange melodische Bögen, tänzerische Episoden und eine geradezu zirzensisch mitreißende Coda zu einem echten „crowd pleaser“. Formal aber ist es, wie Shin herausstreicht, eine „Studie und Hommage“ an die Sonatenhauptsatzform mit ihrem Prinzip zweier kontrastierender Themen und ihrem experimentellen Ausloten dieser Charaktere. Insbesondere Beethoven ist Shin ein Vorbild.

Der Titel des Werks – das im Winter begonnen wurde – war ursprünglich als Arbeitstitel gedacht, doch bald gewann Shin aus dem Kontrast der Jahreszeiten Winter und Frühling kreative Inspiration. Das schroffe „Winterthema“ deutet auf c-moll und es-moll. Daraus erwächst eine fahle, nachdenkliche Fortspinnung in zunehmend atonaler Dissonanzspannung. Dagegen ist das „Frühlingsthema“, das als Referenz an Beethovens „Frühlingssonate“ ebenfalls in F-Dur beginnt, ausgesprochen lyrisch geprägt: „amoroso“ und „nostalgic“ lauten zwei der Vortragsanweisungen. In der Durchführung werden beide Themen in extreme Charaktere getrieben, inklusive einer „fast spöttischen (!) Parodie auf Beethoven“, wie Shin schreibt. Ein grotesker Walzer drängt sich auf. Spieltechniken, die ins Geräuschhafte führen, rasende Läufe, wilde Akkordpassagen schrauben das virtuose Limit immer weiter hinauf. Die Coda endet „in einer fast verzweifelt hoffnungsvollen, ja manischen Atmosphäre mit einer kraftvollen Bekräftigung des Tonika-Akkords“, erklärt Shin: „Es sind oft die kleinen Dinge, in denen wir Hoffnung finden“.

Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach arbeitete als Opern- und Konzertdramaturgin in Köln, Essen und Hamburg und hatte Lehraufträge an der Musikhochschule Hamburg und der Universität Köln inne. Beim Musikverlag Boosey & Hawkes in Berlin ist sie als Vice President Composer Management tätig. Sie schreibt regelmäßig für die Berliner Philharmoniker, die Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, das Lucerne Festival und das Gewandhausorchester Leipzig. 2022 erschien ihre Monographie über die Dirigentin Simone Young.

The Artists

Christian Tetzlaff

Violin

Hamburg-born Christian Tetzlaff studied at the Lübeck Musikhochschule with Uwe-Martin Haiberg and with Walter Levin in Cincinnati and has long been a regular guest on the world’s leading concert stages, both as a soloist and as a chamber musician. He has appeared with many of the world’s leading orchestras, among them the Vienna Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra, the major London orchestras, and the Berliner Philharmoniker (for which he served as artist in residence). Last season, he performed with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, and Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, among others, and served as artist in residence at the Rheingau Music Festival and with the Kammerakademie Potsdam. In 1994, he founded his own string quartet together with his sister, cellist Tanja Tetzlaff, and has toured with the ensemble every year since. Christian Tetzlaff has received numerous awards for his recordings, including the German Record Critics’ Annual Award for his third recording of Bach’s solo sonatas and partitas, which he will also perform live at the Pierre Boulez Saal for his 60th birthday in May 2026. He teaches at the Kronberg Academy and has been artistic director of Heimbach’s Spannungen festival since 2023, succeeding Lars Vogt.

September 2025

Leif Ove Andsnes

Piano

Leif Ove Andsnes was born in 1970 in Karmøy, Norway, and studied with Jiri Hlinka at the Bergen Conservatory. One of today’s most acclaimed pianists, he appears regularly with all major orchestras in the world’s leading music centers. He served as artist in residence with the Berliner Philharmoniker, New York Philharmonic, London Symphony Orchestra, and at Wigmore Hall, among others, and curated the “Perspectives” series at New York’s Carnegie Hall. He enjoys a particularly close artistic collaboration with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, which has included the multi-year projects “A Beethoven Journey” and “Mozart Momentum 1785–86,” featuring both composers’ piano concertos. Leif Ove Andsnes’s recordings have received numerous honors, including seven Gramophone Awards and 11 Grammy nominations. He is the founding director of the Rosendal Chamber Music Festival, was artistic director of California’s Ojai Festival, and served as co-artistic director of the Risør Festival of Chamber Music for almost two decades.

September 2025