Hille Perl Viola da gamba

Lee Santana Theorbo and Lute

Steve Player Guitar and Dance

Program

Louis Couperin

Prélude in D minor

Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe

Les Couplets

Marin Marais

Suite No. 6 in G minor (3ième Livre de pièces de viole)

Antoine Forqueray

La Leclair

Chaconne La Buisson

Jacques Cordier dit Bocan

La Bocanne

Marin Marais

Le Badinage

Le Labyrinthe

Robert de Visée

Prélude

Les Sylvains de M. Couperin

Muzette

Marin Marais

Couplets des Folies d’Espagne

Louis Couperin (c. 1626–1661)

Prélude in D minor

Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe (fl. 1678–before 1700)

Les Couplets – Bergeronnette. Preste

from Concerts pour deux violes egales

Marin Marais (1656–1728)

from the Suite No. 6 in G minor (3ième Livre de pièces de viole) (1711)

Prélude –

Caprice –

Allemande –

Courante –

Sarabande –

Gigue. La Chicane –

Rondeau louré –

Menuet fantasque

Antoine Forqueray (1672–1745)

La Leclair. Très vivement et détaché

Chaconne La Buisson. Gratieusement

from the Suite No. 2 in G major (1ier Livre de pièces de viole)

Jacques Cordier dit Bocan (c. 1580–1653)

La Bocanne

Intermission

Marin Marais

Le Badinage

Le Labyrinthe

from Suite d’un goût étranger (4ième Livre de pièces de viole) (1717)

Robert de Visée (before 1660–1732/33?)

Prélude

Les Sylvains de M. Couperin

Muzette

Marin Marais

Couplets des Folies d’Espagne

from the Suite No. 1 in D minor (2ième Livre de pièces de viole) (1701)

15-year-old Louis XIV dressed as Apollon for his debut at the Paris court in the Ballet de la Nuit, 1653 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Dreams and Dances of the Sun King

It is probably a legend that the composer and violist Marin Marais hid in a hedge to listen to the art of his former teacher, Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe. But whether true or not, this anecdote takes us straight into a fascinating musical era: the second half of the 17th century, Louis XIV’s grand siècle, when the viol, or viola da gamba, had become the most elegant of instruments.

Essay by Anne do Paço

Dreams and Dances of the Sun King

Music at the Court of Versailles

Anne do Paço

It is probably a legend that the composer and violist Marin Marais hid in a hedge to listen to the art of his former teacher, Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe. The latter had shown the young musician the door after only a few months, reasoning that he had nothing more to teach Marais. Perhaps the old master feared the highly talented younger man’s competition? Whether true or not, this anecdote takes us straight into a fascinating musical era: the second half of the 17th century, Louis XIV’s grand siècle. Thanks to Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe, the viol, or viola da gamba, had become the most elegant of instruments, benefiting from a continuously expanding repertoire of great imagination, luminous beauty, and extraordinary refinement. Other plucked string instruments, however, such as the lute, guitar, and theorbo, an import from Italy with a particularly rich sound, were also having a heyday, whether used to support the bass or as solo instruments. In tonight’s concert, Hille Perl, Lee Santana, and Steve Player evoke this period, giving us a colorful portrait of an entire era through its music—its sound, with all its sensuality and magic, reaches our innermost, echoing in an unfiltered way, transporting us to a different place, and opening vistas of consciousness through flights of our imagination.

Little is known about the lives of some of these composers, which include Jacques Cordier, Louis Couperin, Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe, Marin Marais, Antoine Forqueray, and Robert de Visée. Their paths crossed in Paris, either through direct contact or at the royal court. While it was a place where art blossomed, King Louis XIV also used culture as a means to demonstrate his power, shrewdly instrumentalizing the arts as part of his political calculations, alongside diplomacy and war-waging. This did not diminish the quality and diversity of the music—created by composers adept at hitting the right note for any occasion, but also at taking great liberties for their times. Louis XIV engaged the best musicians, painters, sculptors, poets, architects, and landscape gardeners; he also played the guitar himself and had a particular passion for dancing. His support led to the creation of a new genre: the ballet-opera, incorporating large-scale divertissements, whose first major creator was Jean-Baptiste Lully. Moreover, Louis himself engaged in dance practice every day with his court, embodying gods and heroes of antiquity in his legendary appearances in the ballets de cour. The production of dance music flourished as never before. Its composers threw themselves into a daily competition to invent infinite variations, stunning turns, and delicate ornamentations of the easily recognizable, standardized rhythms of the courante, the menuet, sarabande, or gigue—rather like a blossoming Baroque garden, richly imaginative within the corset of strict forms and symmetries. And beyond all that—including the grand operatic performances and official displays for occasions of state—the Sun King also surrounded himself with music during private audiences and even intimate occasions such as going to sleep, thereby encouraging composition for smaller ensembles, a music of subtle, soft sounds.

Enchanting Poetry

Hille Perl opens the program with a Prélude in D minor that conjures enchanting melodic poetry from between the dark resonance of the viol’s low A string and its tender descant. The composer Louis Couperin—an uncle of François Couperin, who is better known today—joined the royal court in 1657, having originally declined the appointment as court harpsichordist as this would have put his mentor and patron Jacques Champion de Chambonnières out of work. Impressed with this reaction, Louis XIV quickly created a new position, making Couperin the descant violist of the royal chamber music. Couperin was known at the time not only for his harpsichord and organ works, but also for having been the organist at the church of Saint-Gervais since 1653, thereby starting a tradition: through 1826, this position would remain in his family. Couperin died in 1661, only 35 years of age. In what seems like an almost Baroque piece of trivia, he lives on to this day not only through his music, but also in the skies: since 1993, the Asteroid 6798 has borne Couperin’s name.

More than a Seventh String

Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe was one of the first to explore the viol’s full expressive spectrum. Rich in polyphonic techniques and ornamentation, his works are distinguished by a strong sense of earnestness and touching introversion: Les Couplets is a good example, beginning as a lively dance that gives way to a chaconne-like passage with a melody that almost seems improvised, unfolding over a harmonic pattern and ending with a vigorous climax. Early-music lovers may recall from Alain Corneau’s 1991 film Tous les matins du monde (All the Mornings in the World), in which Gérard Depardieu played the role of Sainte-Colombe, that he was the one who expanded the viol’s bass spectrum by adding a seventh string. This innovation opened up a whole range of new possibilities, both in terms of resonance and playing technique, which laid the foundation for all the artful inventions of subsequent generations. At the same time, this is one of the few confirmed biographical facts we possess for an artist whose first name has not even come down to us. Sainte-Colombe is believed to have lived until around 1700—a conclusion drawn from the existence of a tombeau, a funeral piece composed by Marais in honor of his admired teacher.

“To Be Revered like No Other”

Marin was born in 1656 in Paris. the son of a cobbler. He grew up in impoverished circumstances but showed a special musical talent, before being appointed a member of the court’s music ensemble at the age of 20. Until his retirement in 1725, he was a violist with the Petit Chœur, Louis XIV’s chamber ensemble, and was said to have played “like an angel.” According to the treatise Défense de la basse de viole by the jurist and cleric Hubert Le Blanc, Marais was “to be revered like no other, a true model of good composition and beautiful execution.” His oeuvre of more than 650 works includes five tragédies lyriques for the operatic stage, but mainly chamber music pieces, numerous suites among them. Always beginning with a prelude, these consist of dance movements in “high style,” such as allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue, but also smaller and lighter forms such as menuet, gavotte, and rondeau, as well as character pieces and caprices, chaconnes and free-form fantasies. Where several dances of the same type are found within these voluminous sequences of movements, these were meant as alternative options from which the performers could choose—a practice also reflected in tonight’s selection of works.

Marais dedicated the last years of his life to preparing for publication his scores for one, two, or three viols with figured bass in a total of five volumes, compellingly documenting the breadth of his output—one example is the Suite No. 6 in G minor from the third volume, published in 1711. One of the highlights is the Suite d’un gout étranger, which is unique in the level of daring employed in portraying the “foreign tastes” of its title. Le Labyrinthe is an experimental search for a way out, full of unusual modulations and an array of emotions ranging from worry, desperation, panic, and resignation to joy. Listening to Le Badinage—a type of dance-like character piece usually representing a sort of musical flirt in a fast duple measure—we seem to hear Marais formulating his thoughts while playing, in a mood of mysterious wistfulness and stern melancholy.

As early as around 1680, Marais had employed the model of the Spanish follia in several of his couplets, which he returned to repeatedly before publishing his Folies d’espagne in 1701. In this set of variations, he pulled out all the technical and musical stops, so to speak, of artful viol playing, achieving interesting effects through changes in tempo and different manners of bowing, weaving a delicate web of melodic ornaments and making the bass line an equal partner in the dialogue. His virtuosity never takes center stage, but seems illuminated from within, while never losing sight of the earnestness that characterized the works of his role model Sainte-Colombe.

A Colorful Figurehead

The dance La Bocan from the early 17th century bears the nickname of a composer; it is a courante with intricately woven figurations, both parts of which consist of an odd number of measures. One can hardly miss the fact that this music is an invitation to dance. It has survived due to its inclusion in the Harmonie universelle published by the theologian, mathematician, and music theorist Marin Mersenne in 1636. Presumably, its composer was Jacques Cordier, who styled himself “La Bocan” after a region in Picardie which had been promised to him. He was one of the most colorful characters of his time: despite the physical limitation of a deformed back, he enjoyed a career as a dancer and choreographer, but was also such an outstanding violinist that the violins employed at the French court were long thereafter known as “les disciples de Bocan.” Cordier, however, had only a loose association with the court; most of his career took place at the English royal court.

Looking beyond the Horizon

It was not uncommon in 17th-century France to observe the musical developments in Italy, as reflected in Antoine Forqueray’s La Leclair with its highly virtuosic runs, while the chaconne La Buisonne unfolds with humorous lightness over its recurring bass. Of all of Forqueray’s works, only 29 compositions for viol and basso continuo are known today, a selection his son Jean-Baptiste published after his father’s death—which may seem surprising, as Antoine Forqueray was said to have lived a life of debauchery at his family’s expense, abusing his wife and children and even sending Jean-Baptiste to jail on false accusations, because he was so afraid of his talented son’s competition. At court, Forqueray enjoyed a meteoric career, having won Louis XIV’s admiration for the quality of his viol playing even as a five-year-old. In 1689, he was appointed a royal chamber musician, joining the illustrious circle responsible for providing music for private functions and the evening serenades in the King’s boudoir.

These intimate performances also included the lutenist, theorbist, and guitarist Robert de Visée, presumably a native of Portugal. His Prélude heard on tonight’s program, which features a rapid succession of ascending and descending scales through the theorbo’s various registers, opens a sequence of dances, some of which were arrangements of other composers’ works, including the rondeau Les Sylvains de M. Couperin (a transcription of a harpsichord piece by François Couperin for one of the summer entertainments in Versailles). De Visée also dedicated two collections of guitar music to the King, and Louis XIV was said to have enjoyed playing these pieces himself—“with the same hand that sends men into battle.”

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

Anne do Paço studied musicology, art history, and German literature in Berlin. After holding positions at the Mainz State Theatre and Deutsche Oper am Rhein, she has been chief dramaturg with the Vienna State Ballet since September 2020. She has published essays on the history of music and dance of the 19th to 21st centuries and has written for Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Vienna’s Konzerthaus, and Opéra National de Paris, among others.

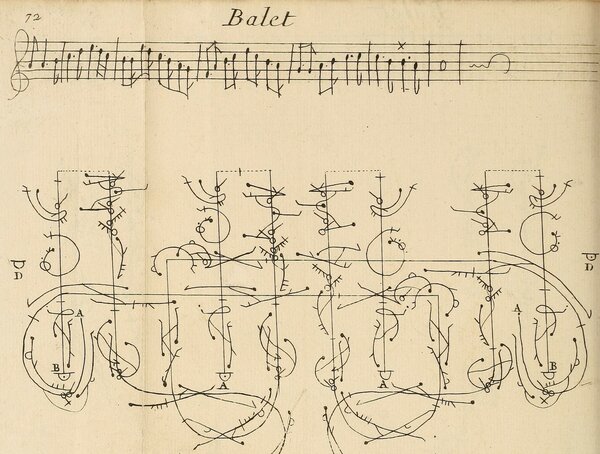

Excerpt from Raoul-Auger Feuillets popular 1700 collection of dances Recueil de Danses (Boston Public Library)

The Artists

Hille Perl, Lee Santana, Steve Player

Born in Bremen, Hille Perl started playing the viola da gamba at the age of five and is among today’s most renowned viol players internationally. She has performed throughout Europe as a soloist, with musical partners such as Daniel Sepec, Lee Santana, Michala Petri, Mahan Esfahani, and Avi Avital, and with her ensembles Los Otros, The Sirius Viols, and The Age of Passions. She also appears regularly with leading Early Music ensembles including the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and the Balthasar Neumann Ensemble and has released numerous recordings, several of which were awarded the ECHO Klassik. She has been a professor at her hometown’s University of the Arts since 2002.

Lee Santana hails from Florida and first trained as a rock and jazz guitarist. He then switched to the lute, theorbo, and cittern, specializing in Early Music. Among his teachers were Stephen Stubbs and Patrick O’Brien. He has been working as a lutenist and composer throughout Europe since 1984, appearing regularly at major festivals and concert halls and collaborating with artists and ensembles such as the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Dorothee Mields, Petra Müllejans, Daniel Sepec, Sasha Waltz, and Hille Perl. In recent years, Lee Santana has also been active as a composer.

Steve Player specializes in Renaissance and Baroque dance music, performing both as a guitarist and a dancer. He regularly works with leading Early Music ensembles such as The Harp Consort, the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, and the Balthasar Neumann Ensemble. Concerts have taken him to the Americas, Australia, and Japan. He also works as a choreographer for opera and television and gives dance workshops for musicians throughout Europe.

October 2024