Julia Hamos Piano

Program

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Sonata in A minor K. 310 (300d)

György Kurtág

Selection from Játékok for Piano

Eight Piano Pieces Op. 3

Leoš Janáček

V mlhách (In the Mists)

Robert Schumann

Fantasy in C major Op. 17

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Piano Sonata in A minor K. 310 (300d) (1778)

I. Allegro maestoso

II. Andante cantabile con espressione

III. Presto

György Kurtág (*1926)

from Játékok for Piano

Hommage à Kurtág Márta (1979)

Felhangjáték (Play with Overtones) 4 (1979)

Capriccioso – luminoso (1986)

Perpetuum mobile (Objet trouvé) (1979)

Tears (1998)

Doina (1992)

Leoš Janáček (1854–1928)

V mlhách (In the Mists) (1912)

I. Andante

II. Molto adagio

III. Andantino

IV. Presto

Intermission

György Kurtág

Eight Piano Pieces Op. 3 (1960)

I. Inesorabile. Andante con moto

II. Calmo

III. Sostenuto

IV. Scorrevole

V. Prestissimo possibile

VI. Grave

VII. Adagio

VIII.Vivo

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Fantasy in C major Op. 17 (1836)

I. Durchaus phantastisch und leidenschaftlich vorzutragen

II. Mäßig. Durchaus energisch

III. Langsam getragen. Durchweg leise zu halten

György Kurtág

Fragments of a Whole

Although as 21st-century audiences we tend to think of multi-movement works as “whole” pieces—not to be divided and, ideally, to be heard from beginning to end without a break—it is perhaps worth remembering that this was not the standard approach to such repertoire for many hundreds of years.

Essay by Katy Hamilton

Fragments of a Whole

Piano Works by Mozart, Schumann, Janáček, and Kurtág

Katy Hamilton

Although as 21st-century audiences we tend to think of multi-movement works as “whole” pieces—not to be divided and, ideally, to be heard from beginning to end without a break—it is perhaps worth remembering that this was not the standard approach to such repertoire for many hundreds of years. And it makes a significant difference to the way we hear and understand music if we take a moment to think about why a specific piece might not be continuous: what it means to have breaks, fragments, and changes of scene. Julia Hamos’s recital program brings together a selection of works from the late 1770s to the present day, which all, in their different ways, gather together movements or fragments to make a whole. Their juxtapositions here remind us of the power of silence, and of arranging smaller paragraphs (sometimes serious, sometimes silly) to reveal new stories and connections.

A Sturm und Drang Sonata

In 1778, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s father sent him to Paris in the company of his mother to try to further his reputation and look for possible offers of work. The trip was not a happy one: Mozart was unimpressed by the city, deeply disliked the music he heard there, and found the professional scene gossipy and malicious. Worse still, his mother became seriously ill in June and died in early July, with her 22-year-old son at her bedside. “Indeed,” he later confessed, “I wished at that moment to depart with her.”

Throughout these months, Mozart did what he could (with seemingly little enthusiasm) to gain recognition and promote his music. Among his compositions from that summer is the Piano Sonata in A minor K. 310, almost certainly inspired by the fashionable Sturm und Drang style of the moment and demonstrating new knowledge of the dynamic range of the pianoforte at a time when the harpsichord was still much in circulation as a keyboard instrument. The grandly tragic Allegro maestoso brilliantly balances the throbbing urgency of its opening chords with fluid passages of fast-moving figuration: without changing tempo, we seem to be moving at quite different speeds at different points within the movement. The mood is completely changed by the arrival of the gorgeously expansive Andante, with a highly expressive singing soprano melody; and we wholly switch gears again with a ferociously compressed Presto, restless and relentless in its major-minor alternations and interrupted themes.

“I Understand Music Only When I Teach…”

Since 1973, the Hungarian composer György Kurtág has written multiple volumes of Játékok—“Games”––for keyboard instruments. He had been approached that year by a piano teacher, Marianne Teöke, who asked him to produce some short pedagogical pieces for her students. In approaching this task, Kurtág found new enthusiasm for composition as he sought to find new ways of engaging young players. “I understand music only when I teach,” he has explained. “Even if I listen to it or play it myself, it’s not the same as working on it and trying to understand it for others.” Hamos is, after all, a grand-pupil of Kurtág, through her studies with András Schiff, so it seems wholly appropriate that she has chosen to include a group of six of Játékok in this program. These include a beautiful, gentle, sonorous homage to his wife Márta; experiments with the ringing harmonics of the piano itself; deeply touching miniatures featuring dynamics as extreme as quadrule piano; and a witty, glittering birthday present (Capriccioso – Luminoso) for the artist Jenő Szervánszky.

A decade earlier in 1960, Kurtág’s Eight Piano Pieces Op. 3 were premiered in Darmstadt by the Budapest-born pianist Andor Losonczy. The music was profoundly influenced by Kurtág’s time in Paris in 1957–8, when he studied with Olivier Messaien and Darius Milhaud, and had sessions with the art psychologist Marianne Stein. Since Kurtág was struggling to compose during this period, Stein suggested taking creation back to first principles: ways to connect two notes, for instance. Kurtág also experimented with model-making and drawing as a way of finding ideas. “I drew something: there were stars at the edges and in the middle something wriggling. I still have it to the present day, and that’s what I attempted to set to music in the seventh of Eight Piano Pieces.” The opus draws together a sequence of contrasting miniatures, each playing with very specific musical processes, such as ostinatos, tremolos, gliassandi, and huge registral leaps (virtuosically rendered in the fifth piece). Despite their brevity, they are highly arresting and full of drama—and in several cases, theatrical in their physical presentation.

An Obscure Landscape

Kurtág was two years old when Leoš Janáček died. Janáček had become the most famous Moravian composer of his generation—but had only come to enjoy this position in the last few decades of his life. V mlách (“In the Mists”) was published in 1912, by which time he was beginning to enjoy greater success and recognition. Also, crucially, he had just heard Debussy’s Reflets dans l’eau in a concert in Brno in January 1912. Although the piece was hardly new—it had been published in 1905—Debussy’s music was little known in Moravia at the time, and it may even have been the first of his compositions that Janáček got to hear. “In the Mists” seems a perfect response, a nature title at once evocative and ambiguous; there are no further clues in Janáček’s writings or recorded conversations to suggest any other particulars. That the pieces were written at a time in the composer’s life when he was struggling to complete major works, or find theaters willing to stage his operas, might suggest an autobiographical aspect to the disorientation of being in an obscure landscape. Whatever the motivation, the sense of mistiness, of uncertainty, is clear in each of these pieces. They each feature several highly contrasting musical ideas: lyrical (the opening melodies of the first and third), melancholy and impassioned (the fourth), hesitant, such as the opening of the second, which rapidly spawns a little jabbing secondary idea, as if poking the reluctant first speaker in the ribs. Themes return in different keys, drifting away from their point of departure or, indeed, never firmly establishing a sense of “home” in the first place, lost in a mist-covered musical world.

“In This Colorful Earthly Dream…”

The final piece on tonight’s program has an extensive history and went through several different versions before reaching the form with which we are now familiar. Robert Schumann’s Fantasia in C major was completed in 1838. (It it is extraordinary to think, given the worlds between them, that the year of Janáček’s birth was also the year of Schumann’s suicide attempt and subsequent removal to the sanitorium at Endenich, where he was to spend the last two years of his life.) Its conception is complex, and the first movement seems to have been intended, initially, as an independent composition entitled “Ruines,” written in 1836 when Schumann and Clara were banned from seeing each other by her overbearing father. Later that same year, on hearing of an initiative to construct a Beethoven monument in Bonn, Schumann hit upon the idea of expanding the single movement into part of a “Grosse Sonate” entitled (this time in German rather than French), “Ruinen. Trophäen. Palmen” and offering part of the proceeds from publication towards the building of the monument. Unable to find a publisher, he probably set the work aside until 1838, when the Fantasia was revised, remodeled, and lost its picturesque title. Instead, Schumann placed a quotation from Friedrich Schlegel’s Die Gebüsche at the head of the first edition, published in 1839:

Through all the tones

In this colorful earthly dream,

One quietly drawn-out tone

Sounds for one who listens secretly.

“Aren’t you the ‘tone’ in the motto?”, Robert wrote to Clara in the summer of 1839. “I believe so.” These secret tones, one can only surmise, form the quotation from Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (an appropriate choice at this point in their courtship), which is hinted at from the very opening of the piece—a nod, too, to the earlier intended function of the work as a monument to the great man—and eventually emerges clearly at the close of the first movement. The second movement has all the poise and fire of Florestan (one of Schumann’s two poetic alter egos) in its noble march, leaping lines, and virtuosic coda; the third is surely Eusebius, dreaming and hymnal, a magical apotheosis that ends in quiet and perfect contentment.

Katy Hamilton is a writer and presenter on music, specializing in 19th-century German repertoire. She has published on the music of Brahms and on 20th-century British concert life and appears as a speaker at concerts and festivals across the UK and on BBC Radio 3.

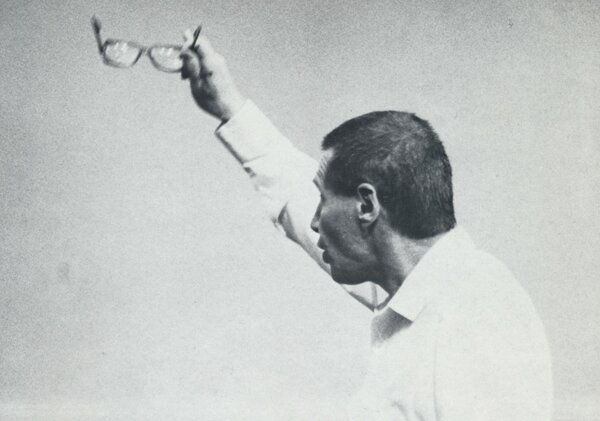

Leoš Janáček, 1914

Durch alle Töne tönet…

Zwei großformatige klassisch-romantische Werke von Mozart und Schumann rahmen in Julia Hamos’ Soloprogramm Miniaturen von György Kurtág und Leoš Janáček.

Essay von Jürgen Ostmann

Durch alle Töne tönet…

Klavierwerke von Mozart, Schumann, Janáček und Kurtág

Jürgen Ostmann

Romantisch schroff

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozarts Klaviersonate a-moll KV 310

„Schreibe kurz – leicht – popular“, empfahl Leopold Mozart im August 1778 seinem Sohn nach Paris. Als hätte er geahnt, dass dieser gerade erst ein Werk komponiert hatte, das völlig gegensätzlich ausfiel: lang, schwer und eher schroff. Mit seiner a-moll-Klaviersonate KV 310 konnte Mozart in der französischen Hauptstadt nicht reüssieren. Stattdessen liebte das Publikum des 19. Jahrhunderts das Stück: Hier war kein heiter-verspielter Rokoko-Mozart zu hören, sondern der tragische Tonsetzer des Don Giovanni, der späten g-moll-Symphonie oder des Requiems. Außerdem ließ sich rund um die Sonate eine romantische Legende stricken: Da ein konkreter Kompositionsanlass nicht bekannt war, spekulierte man, Mozart habe das Stück nur für sich geschrieben, als Selbstbekenntnis in einer verzweifelten Lebenssituation. Tatsächlich fallen in die gleiche Zeit die Zurückweisung durch seine große Liebe Aloysia Weber und der Tod der Mutter.

Obgleich solcherlei biographische Interpretationen als überholt gelten, bleibt der dunkle, hochdramatische Charakter der Sonate festzuhalten. Den Grundton gibt schon das feierlich punktierte Hauptthema des ersten Satzes vor. Eingeleitet durch einen dissonanten Vorschlag, erinnert sein Rhythmus an einen Trauermarsch. Die dichte, fast orchestrale Akkordbegleitung wird immerhin bald von leichteren Figurationen abgelöst. Das Sechzehntelketten des zweiten Themas beginnen in C-Dur, was allerdings nichts am leidenschaftlich intensiven Tonfall der Musik ändert. Auch im weiteren Verlauf sorgen insistierende Rhythmen, Dissonanzen und chromatische Wendungen, auch ein fast gewaltsamer Wechsel zwischen Pianissimo und Fortissimo für eine bedrückende Atmosphäre. Lyrische Entspannung scheint zunächst das Andante zu bieten. Allerdings erinnern schon bald schwere Akkorde und Arpeggien im Bass an den unruhigen Gestus des Kopfsatzes. Ein freier Mittelteil, der an der Stelle einer Durchführung steht, nimmt die Dramatik des Beginns wieder auf. Erneut vermitteln krasse dynamische Wechsel innere Erregung. Wie ein unheilvolles Perpetuum mobile wirkt das abschließende Presto, ein Rondo mit einem einfachen, rhythmischen Hauptthema. Gerade die leiseren Passagen, die den Satz prägen, verstärken noch seine gespenstische Unrast.

Pädagogische Inspiration

György Kurtágs Játékok

Charakteristisch für die Werke des Ungarn György Kurtág ist zum einen ihre aphoristische Kürze, zum anderen die außerordentliche Vielfalt der musikalischen Mittel. Oft hat die spezielle Klangqualität eines Stückes mit Widmungsträger:innen zu tun, deren Stil Kurtág aufgreift oder deren Persönlichkeit er in Tönen darstellt. „Hommage à …“ oder „In memoriam …“ sind denn auch häufige anzutreffende Werktitel in seinem Œuvre; darin finden sich Hommagen an zahlreiche Komponisten der Vergangenheit, aber auch an Freunde, Kolleginnen, künstlerische Partnerinnen –darunter auch seine Frau Martá, mit der er oft und gern gemeinsam auftrat. Typisch für Kurtág erscheint außerdem, dass er viele Stücke in offenen Werkreihen zusammenstellte, die unabgeschlossen weiterwuchsen und in beliebiger Auswahl aufgeführt werden können. Zu diesen zählen auch das 1973 begonnene Játékok („Spiele“) für Klavier zu zwei oder vier Händen. Die Reihe umfasst mittlerweile mehrere hundert Miniaturen.

Die ersten Bände von Játékok lassen gelegentlich noch an eine pädagogische Sammlung von Stücken steigenden Schwierigkeitsgrads denken, wie Béla Bartók sie mit seinem Mikrokosmos schuf. Und tatsächlich verfolgte Kurtág anfangs auch didaktische Ziele: „Die Anregung zum Komponieren der ‚Spiele‘“, so schreibt er im Vorwort zur Notenausgabe, „hat wohl das selbstvergessen spielende Kind gegeben. Das Kind, dem das Instrument noch ein Spielzeug ist. Es macht allerlei Versuche mit ihm, streichelt es, greift es an. Es häuft scheinbar unzusammenhängende Klänge, und wenn dies seinen musikalischen Instinkt zu erwecken vermochte, wird es nun bewusst versuchen, gewisse zufällig entstandene Harmonien zu suchen und zu wiederholen. […] Freude am Spiel, an der Bewegung – mutiges, rasches Durchlaufen der ganzen Klaviatur gleich am Anfang des Klavierlernens, ohne umständliches Herumsuchen der Töne, ohne Abzählen der Rhythmen – solch eine anfangs noch unbestimmte Vorstellung brachte diese Sammlung zustande.“

Die späteren Bände setzen allerdings neue Akzente. Kurtág gab ihnen den Untertitel Naplójegyzetek, személyes üzenetek („Tagebucheintragungen, persönliche Botschaften“) und fasste darin Imitationen historischer Stile, kleine Dramen, Geburtstagsgrüße (etwa Capriccioso – luminoso zum Achtzigsten des Malers Jenő Szervánsky) und vieles mehr zusammen. Játékok enthält die unterschiedlichsten Einzelstücke: witzige und stimmungsvolle, abstrakte und klangmalerische, elementar einfache und durchaus virtuose Sätze.

Strenge und Humor

György Kurtágs Acht Klavierstücke op. 3

Als er 1960 seine Acht Klavierstücke abschloss, war Kurtäg zwar schon 34 Jahre alt, stand aber als künstlerisch eigenständiger Komponist noch ganz am Anfang seiner Laufbahn. Studiert hatte er von 1946 bis 1955 in Budapest bei Sándor Veress und Ferenc Farkas, und seine Kompositionen aus dieser Zeit entsprachen ganz den Forderungen des Sozialistischen Realismus. Doch nach dem Volksaufstand von 1956 erhielt Kurtág einen Reisepass und nutzte die Gelegenheit, in Paris seine Ausbildung zu vervollständigen, unter anderem bei Darius Milhaud und Olivier Messiaen. Bedeutsam war auch seine Arbeit mit Marianne Stein, die ihn lehrte, von elementarstem Material ausgehend zu präzisem Ausdruck der jedem Stück zugrundeliegenden Idee zu gelangen. Der ungarischen Kunstpsychologin widmete er 1959 ein Streichquartett, das er zu seinem Opus 1 erklärte, seinem ersten gültigen Werk.

Die Acht Klavierstücke op. 3, zusammen nur etwa sechs Minuten lang, sind in ihrer Konzentration vergleichbar mit den Kompositionen Anton Weberns, die Kurtág sich in Paris fast komplett abschrieb. Auch die von Webern angewandte Zwölftontechnik kommt in einigen Sätzen zum Einsatz – insbesondere in Nr. 5, wo eine Zwölftonreihe von ihrem sogenannten Krebs (der rückwärts gelesenen Grundreihe) begleitet wird. Das scheinbar streng konstruierte Stück zeugt allerdings auch von Humor: Obwohl schon zu Beginn „Prestissimo possibile“ überschrieben und kaum mehr als zehn Sekunden dauernd, enthält es noch mehrere Temposteigerungen.

Rätselhafte Miniaturen

Leoš Janáčeks Im Nebel

Zwei Einflüsse waren es vor allem, die Leoš Janáčeks eigenwilligen Personalstil prägten: zum einen die Volkslieder und -tänze seiner tschechischen Heimat, die er mit wissenschaftlichem Ehrgeiz aufzeichnete – Jahrzehnte bevor Bartók und Kodály in Ungarn Ähnliches unternahmen. Zum anderen studierte Janáček intensiv verschiedene Aspekte der Alltagssprache – das An- und Abschwellen, Steigen und Fallen der Stimme und vieles mehr. Stilisierte „Sprechmelodien“ bilden denn auch die Grundlage zahlreicher Kompositionen Janáčeks, prägen deren kurze, vielfach wie abgerissen wirkende melodische Fragmente und verursachen die häufigen Taktwechsel, ungewöhnlichen Intervallschritte und freien Formen. Die Herleitung aus Sprechmelodien erklärt auch, warum Janáčeks Klaviermusik nicht eigentlich pianistisch oder gar virtuos klingt, obwohl das Klavier sein Hauptinstrument war.

Nur drei größere Werke widmete Janáček ihm: Neben der Sonate 1.X.1905 sind dies die neunteilige Sammlung Auf verwachsenem Pfade (1901–08) und der vier Miniaturen umfassende Zyklus Im Nebel (1912/13). Über den letzteren Titel ist viel gerätselt worden, zumal Überschriften für die Einzelstücke fehlen. Vielleicht liegt ihnen ein verborgenes Programm zugrunde – oder das Nebelhafte beschränkt sich auf den zögernd-tastenden Charakter, der sie zu verbinden scheint. Im eröffnenden Andante kontrastiert das sanfte, tonal ambivalente Thema der Rahmenteile mit den choralartigen Melodiephrasen und fallenden Tongirlanden des zentralen Abschnitts. Ähnlich wie dieser Mittelteil lebt auch das folgende Molto adagio vom Aufeinandertreffen gegensätzlicher Elemente: Ein ruhiges, wehmütiges Thema wechselt sich ab mit raschen ornamentalen Figuren. Das dritte Stück, Andantino überschrieben, klingt wie ein immer wieder abbrechendes und neu ansetzendes Lied; seine Stimmung wird von den drohenden Fanfarenmotiven des Mittelteils nur kurz gestört. Am stärksten fragmentiert erscheint das Finale, dessen Anfangsbezeichnung „Presto“ in die Irre führt: In Wahrheit prägen ständige Tempo- und Taktwechsel seinen unruhigen Verlauf.

Komponieren für Beethoven

Robert Schumanns Fantasie op. 17

Der Streit erhitzte im 19. Jahrhunderts die Gemüter: Kann und soll Musik ein „Programm“ wiedergeben, also mit rein instrumentalen Mitteln eine außermusikalische Idee, ein Bild oder eine Handlung im Geist entstehen lassen? Oder folgt sie besser nur ihrer eigenen inneren Logik? Robert Schumann besaß eine bemerkenswerte kompositorisch-dichterische Doppelbegabung. Man sollte meinen, dass sie ihn ganz natürlich ins Lager der Programmmusik hätte führen sollen, der neuartigen Verbindung von Musik und Literatur. Doch tatsächlich nahm er in der ästhetischen Diskussion eine differenzierte, teils auch widersprüchliche Position ein: Vielen Klavierwerken gab er suggestive Satzüberschriften, die aber über etwaige „Inhalte“ nur wenig aussagen. Dass es solche Inhalte geben könnte, legen neben Titeln und Vortragsbezeichnungen auch die musikalischen Verläufe selbst nahe: die jähen Stimmungsumschwünge und schroffen Gegensätze, die Abschweifungen und Rückblenden, die symbolischen, oft versteckten Zitate. Schumann nutzte literarische und private Assoziationen, um Musik für sich selbst und für seine Hörer:innen poetisch „aufzuladen“. Aber gegenüber einem Bewunderer, der mehr über die Hintergründe wissen wollten, erklärte er, „man sollte tunlichst nicht alles in Worte fassen und aussprechen.“

Sein Opus 17 bezeichnete Schumann erst nach längerem Schwanken als „Fantasie“. Ursprünglich war das Stück als „Große Sonate für Beethoven“ gedacht; der Erlös sollte der Errichtung eines Beethoven-Denkmals zugutekommen. Im Lauf der relativ langen Entstehungszeit (1836–38) zog er auch Titel wie „Fata Morgana“, „Obolen auf Beethovens Monument“ und „Dichtungen“ in Erwägung, dazu poetische Satzüberschriften wie „Ruinen, Trophäen, Palmen“ oder „Ruine, Siegesbogen, Sternenlicht“. Doch als Schumann das Werk 1839 veröffentlichte, stellte er lediglich dem ersten Satz ein literarisches Motto von Friedrich Schlegel voran:

Durch alle Töne tönet

Im bunten Erdentraum

Ein leiser Ton gezogen

Für den, der heimlich lauschet.

Als Fantasien werden üblicherweise einsätzige Stücke von quasi-improvisatorischer Anlage bezeichnet. Schumanns dreisätzige Fantasie steht jedoch in der Nachfolge von Beethovens Sonaten op. 27, die im Titel den Zusatz „quasi una fantasia“ tragen. Der erste Satz enthält gegen Ende als direktes Beethoven-Zitat die Liedzeile „So nimm sie hin denn, meine Lieder“ aus dem Zyklus An die ferne Geliebte. Der Mittelsatz nimmt stellenweise den Charakter eines Triumphmarsches an, und das Finale entfernt sich durch sein langsames Tempo und den fast durchgehend leisen Vortrag weit vom typischen Sonatenschlusssatz.

Jürgen Ostmann studierte Musikwissenschaft und Orchestermusik (Violoncello). Er lebt als freier Musikjournalist und Dramaturg in Köln und arbeitet für verschiedene Konzerthäuser, Rundfunkanstalten, Orchester, Plattenfirmen und Musikfestivals.

The Artist

Julia Hamos

Pianist

American-Hungarian pianist Julia Hamos studied with Christopher Elton at London’s Royal Academy of Music, with Richard Goode at the Mannes School of Music in New York, and with Sir András Schiff at the Barenboim-Said Akademie; she completed her education at the Kronberg Academy. Winner of the Sterndale Bennett Prize of the Royal Academy of Music and the Fidelman Award of the Mannes School, she has performed at venues including London’s Wigmore Hall, Beethovenhaus Bonn, New York’s Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and the Liszt Academy in Budapest. She has also appeared at Poland’s Krzyżowa-Music, the Trasimeno Music Festival in Italy, IMS Prussia Cove in Cornwall, the Verbier Festival, and at Kronberg’s Chamber Music Connects the World with Tabea Zimmermann and Christian Tetzlaff. She has collaborated on interdisciplinary projects with the Martha Graham Dance Company, the New English Ballet Theatre, and the theater department of New York’s New School. At the Pierre Boulez Saal, Julia Hamos appeared as the soloist in Ligeti’s Piano Concerto with the Boulez Ensemble and Matthias Pintscher last season.

February 2025