Claron McFadden Soprano

Julius Drake Piano

Toby Jones Recitation

Program

Walt Whitman

Excerpts from Leaves of Grass and other texts

Reading in English

Settings by

Kurt Weill, Ned Rorem, Leonard Bernstein, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Frank Bridge, Oliver Knussen, Paul Hindemith, George Crumb

Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

Excerpts from Leaves of Grass and other texts

Reading in English

That Music Always Round Me

Kurt Weill (1900–1950)

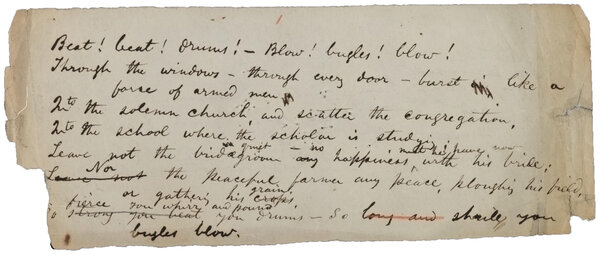

I. Beat! Beat! Drums!

II. O Captain! My Captain!

III. Come up from the Fields, Father

from Four Walt Whitman Songs (1942/47)

Ned Rorem (1923–2022)

Look Down, Fair Moon

from Five Poems of Walt Whitman (1957)

II. A Specimen Case

III. An Incident

V. The Real War

from War Scenes (1969)

Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990)

To What You Said…

from Songfest (1977)

Intermission

Joy, Shipmate, Joy!

Art-Singing and Heart Singing (Broadway Journal, November 29, 1845)

I Hear America Singing

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958)

Joy, Shipmate, Joy!

Frank Bridge (1879–1941)

The Last Invocation

Review of Leaves of Grass (The Critic, April 1, 1856)

Oliver Knussen (1952–2018)

The Voice of the Rain

from Whitman Settings Op. 25 (1991)

Conversation between Walt Whitman and Horace Traubel, May 16, 1888

Sing On There in the Swamp!

Paul Hindemith (1895–1963)

O, nun heb du an, dort in deinem Moor

from Drei Hymnen von Walt Whitman Op. 14 (1919)

George Crumb (1929–2022)

from Apparition for Soprano and amplified Piano (1979)

I. The Night in Silence

Vocalise I. Summer Sounds

II. When Lilacs Last

Dark Mother

Vocalise II. Invocation

IV. Approach, Strong Deliveress

Vocalise III. Death Carol

V. Come Lovely Soothing Death

VI. The Night in Silence

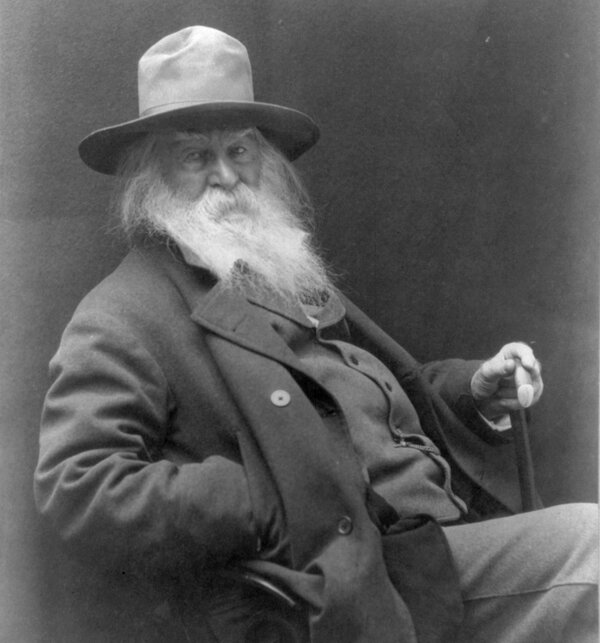

Walt Whitman in 1887 (© Library of Congress, Washington D.C.)

In Space and Sky

When describing Walt Whitman, fellow poet Ezra Pound simply declaimed, “He is America.” Whitman’s output often spoke with a heightened, musical tongue, yet it was only after his death, in 1892, that composers began to set his poetry and made Whitman as much a musical fixture as he was a literary one.

Essay by Gavin Plumley

In Space and Sky

Setting Walt Whitman to Music

Gavin Plumley

When describing Walt Whitman, fellow poet Ezra Pound simply declaimed, “He is America.” In his confidence, Pound summed up the hopeful, transcendental, and profoundly patriotic force of the 19th-century New Yorker’s verse. Yet in Leaves of Grass, Whitman’s major collection first published in 1855, he had provided his own self-portrait: “an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, disorderly, fleshly, and sensual, no sentimentalist, no stander above men or women or apart from them, no more modest than immodest.” Sincere he may have been, yet, like the sensual poetry contained within, Whitman divided opinion. Some thought him and his work obscene, while others took the latter as a rallying call—an attitude the writer himself adopted during the Civil War.

Whitman’s output often spoke with a heightened, musical tongue, yet it was only after his death, in 1892, that composers began to set the poetry with alacrity. It found a particularly ripe home during the fin de siècle, thanks to the rejection of Victorian moral exactitude, including for composers such as Charles Villiers Stanford, Charles Wood, and Hubert Parry. Leading a charge not in America but in Britain, their early adoption of Whitman was to be followed no less avidly by Frederick Delius and Percy Grainger, Ralph Vaughan Williams and his close friend Gustav Holst, as well as Frank Bridge. And the trend was mirrored in continental Europe, namely by Karl Amadeus Hartmann, Paul Hindemith, and Franz Schreker. There had, of course, been early Whitman settings on the poet’s own side of the Atlantic, but it was only later in the 20th century, with the composers featured on tonight’s program, that he became as much a musical fixture in the United States as he was a literary one.

The Adopted American

When Kurt Weill fled Nazi Germany and eventually settled in New York in the mid-1930s, he may well have been familiar with the various earlier responses to Whitman, including Hindemith’s Drei Hymnen von Walt Whitman of 1919, of which Claron McFadden and Julius Drake perform the second, a setting of Sing On, There in the Swamp! in German translation. When it came to writing his own, however, Weill proved typically chameleon-like and embraced the vernacular of his adopted home. His flair for plurality, witnessed in the collaborations with Brecht, was likewise manifest in his response to American culture, from ballads to Broadway. And, according to Virgil Thomson, each new work offered “a new model, a new shape, a new solution,” thereby throwing down the gauntlet to both contemporaries and successors.

Three of Weill’s Four Walt Whitman Songs are heard tonight. The two outwardly patriotic verses—Beat! Beat! Drums!, with its call for union, and O Captain! My Captain!, written after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln—were composed in 1942, the same year Weill arranged The Battle Hymn of the Republic and The Star-Spangled Banner, as U.S. forces joined the war. If Beat! Beat! Drums! has a Brechtian aloofness, O Captain! My Captain! is more heartfelt, before the 1947 Come Up from the Fields, Father combines the two approaches in a vivid scena.

Both Sides

It was for Weill’s later adulatory obituarist, Virgil Thomson, that the young Indiana-born Ned Rorem acted as a secretary and music copyist during the 1940s. Rorem also studied with Aaron Copland at Tanglewood and with Arthur Honegger in Paris, before returning home, specifically to live in New York, in 1958. Unlike many of the composers who had previously drawn inspiration from Whitman’s verse, Rorem was gay and found a strong attraction to the qualities that had prompted censure during the poet’s lifetime. Likewise, it was thanks to the fluid prosody of Rorem’s sung works that he formed a rich, posthumous alliance across the span of a century: from the publication of Leaves of Grass to the gay liberation movement, of which Rorem was something of a hero.

War Scenes dates from 1969 and was composed against the backdrop of Vietnam, the inauguration of Richard Nixon, and the growth of an anti-war message at home. Whitman had written the texts, published as Specimen Days, at the beginning of the 1880s. As a collection, they marked something of a return to the geography of Leaves of Grass, in that they were written in the same South Jersey community of Laurel Springs. As Whitman worked in his Edenic haven, he recalled the horrors of the Civil War, including the fine examples “of youthful physical manliness” he had nursed in the field hospitals. Rorem’s songs are unmistakably mournful, dedicated “to those who died in Vietnam, both sides, during the composition: 20–30 June 1969,” though they also speak of uncontainable rage, communicated as much in the piano’s rapid fire as by the singer’s dramatic monody.

Songs of Plurality

Rorem’s work similarly features in the handful of individual settings that follow, including one of his Five Poems of Walt Whitman from 1957. Rorem’s friend and sometime lover Leonard Bernstein likewise ensured that Whitman had a central role to play in his own, much later composition Songfest. Commissioned to celebrate the Bicentennial in 1976, it was not completed in time, though Bernstein continued work on the project. He had wanted to show the history of the United States as one of conflict between plural and puritan forces, offering his own unabashed celebration of multiculturalism in response. And like Rorem, the bisexual Bernstein no doubt felt affinity with Whitman, whose confession To What You Said… was to become the fourth of the 12 songs in the cycle.

Frank Bridge’s The Last Invocation, written in 1918, is the earliest composition on tonight’s program and demonstrates the early British adoption of Whitman for musical purposes. Once more, the poet’s experiences of the American Civil War are transposed to another conflict, as more youths go “noiselessly forth.” Bridge may have provided a model, though his most famous pupil, Benjamin Britten, never responded directly to Whitman’s verse—the writer’s work was, perhaps, too closely linked to Vaughan Williams for Britten’s taste. Nonetheless, he was certainly to remain a point of inspiration, not least in the homoerotic elements of the opera Billy Budd.

Instead, the British link skips a generation, to reappear in the output of Oliver Knussen, a later director of Britten’s Aldeburgh Festival, before he took charge of contemporary music at Tanglewood, a former place of study. In 1991, during the composer’s second association with the Massachusetts music festival and training ground, he wrote his Whitman Settings. “All four poems,” Knussen explained, “muse on things in space or the sky, and all four songs grow from the short idea heard at the outset.” Melodically supple, harmonically rich, The Voice of the Rain is the last of the set.

Return of the Native

This evening’s program, however, closes with George Crumb’s 1979 Apparition for soprano and amplified piano. It may constitute the most recent response to Whitman’s writing heard tonight, though many composers continue to be inspired by the poet’s work, not least John Adams in his 1987 meditation on the AIDS crisis, The Wound Dresser. First performed six years earlier, Crumb’s Apparition emerged during the earliest days of that epidemic, as the U.S. Center for Disease Control began to publish articles concerning the development of a rare lung infection, as well as cases of an unusually aggressive cancer, among previously healthy gay men on both the East and West Coasts.

Crumb had begun his “elegiac songs and vocalises” before these tragic discoveries, though Apparition certainly takes its own place within the corpus of musical, literary, and theatrical works reacting to the crisis. And given that Crumb had previously drawn inspiration from—and responded to—historical events, such as Apollo 11 (Night of the Four Moons in 1969) and the Vietnam War (Black Angels in 1970), context is germane.

The work features six numbered songs and three interlinking vocalises. Lasting just over 20 minutes, the cycle’s clear structure nonetheless belies the music’s theatrical nature, in which the pianist is instructed to pluck, strum, and drum the strings of the instrument, while the singer mimics the sounds of nature—the locus of Whitman’s solace in the face of war—while whispering and humming, as well as singing into the piano’s resonant soundboard. The text is drawn from the famous elegy to Lincoln, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, though Apparition studiously eschews any direct reference to the fateful events of 1865 in favor of a wider meditation on mortality, as Crumb’s colleague and fellow composer William Bland explained: “Each song and vocalise form a piece of a larger vision, eventually coalescing as a tableau. The literary and musical materials focus on concise, highly contrasting metaphors for existence and death. Yet Crumb’s cycle offers the listener reassurance. For just as in Whitman’s verse, death is never depicted as an ending of life. Instead, it is circular, always a beginning or an enriched return to a universal life-force.”

Marking that power, the work finally reprises the evocative strumming and aching intervals of The Night in Silence. Heard as if in echo, remembrance—or both—the song’s melancholy grace notes, its melismas and modalities, all mirror the extraordinary scope of the musical culture that Whitman’s work has inspired since his death, just over 130 years ago.

Gavin Plumley is a cultural historian who writes, broadcasts, and lectures widely on the art and music of Central Europe. He appears frequently on the BBC and contributes to newspapers, magazines, and opera and concert programs worldwide. His first book, A Home for All Seasons, was published last year.

Autograph draft for Beat! Beat! Drums! (© Library of Congress, Washington D.C.)

Bilder von Liebe und Krieg

Er sei „America’s poet“, beschrieb Ezra Pound seinen zwei Generationen älteren Dichterkollegen Walt Whitman. Whitmans Texte geben zutiefst persönliche Einblicke in seine Gedankenwelt und repräsentieren gleichzeitig Amerika und die USA politisch wie gesellschaftlich. Trotz aller – manchmal grausamer – Konkretheit, die in Whitmans Gedichten begegnet, spricht aus ihnen stets eine universelle und unvergängliche Stimme, die den Schriftsteller nicht umsonst zum Wegbereiter der literarischen Moderne in Amerika werden ließ. Angesichts dessen ebenso wie der subtilen Musikalität seiner reimlosen Verse verwundert es nicht, dass Komponist:innen sich bis heute von seinen Schriften entzünden lassen.

Essay von Meike Pfister

Bilder von Liebe und Krieg

Lieder nach Walt Whitman

Meike Pfister

„Wir leben inmitten von Alarmrufen; die Zukunft ist von Angst umnebelt; mit jeder Zeitung, die wir lesen, erwarten wir eine neue Katastrophe“, heißt es in Abraham Lincolns „Lost Speech“ aus dem Jahr 1856. Zur gleichen Zeit veröffentlichte Walt Whitman die zweite, erweiterte Ausgabe seines im Vorjahr erschienenen, zuerst nur zwölf Gedichte umfassenden Bandes Leaves of Grass. Im Laufe seines Lebens folgten noch acht weitere überarbeitete und mehrere hundert Gedichte umfassende Versionen, die zutiefst persönliche Einblicke in die Gedankenwelt des Autors geben und gleichzeitig Amerika und die USA politisch sowie gesellschaftlich repräsentieren. Er sei „America’s poet […] He is America“, formuliert es der zwei Generationen jüngere Dichter Ezra Pound. Weniger anerkennend befand ein Kritiker des Boston Intelligencer 1855: „Sein unzusammenhängendes Geschwätz hat weder Witz noch Methode, und es scheint uns, dass er ein entlaufener Irrer sein muss, der in einem bedauernswerten Delirium tobt.“ Worte, die Whitman am Ende der zweiten Auflage von Leaves of Grass unverhohlen abdrucken ließ. (Auf Deutsch erschien eine Auswahl der Gedichte erstmals 1889 unter dem Titel Grashalme.)

Zeit seines Lebens brannte die Kontroverse um die in freien Versen gehaltene Dichtung, die sich gern auch in (homo-)erotischen Inhalten erging. Beziehungen zwischen Männern kommen in Leaves of Grass jedoch auch im weiteren Sinn Bedeutung zu: als Kameradschaft, wie sie im Bürgerkrieg ab 1861 erlebt wurde. In seiner eingangs zitierten Rede hatte Lincoln den blutigen Konflikt zwischen Nord- und Südstaaten, der zu einer der schwärzesten Perioden in der Geschichte der USA werden sollte, scheinbar vorausgeahnt. Über 600.000 Amerikaner:innen starben, mehr als in beiden Weltkriegen und dem Vietnamkrieg zusammen. Whitman, der hinter Lincoln stand und damit zu den Gegnern der Sklaverei gehörte, erlebte den Krieg zwar nicht an der Front, engagierte sich jedoch als Pfleger in Krankenhäusern und war damit unmittelbar am Kriegsgeschehen beteiligt. Gedichte und Tagebuchaufzeichnungen, wie sie im heutigen Programm vor allem in den Vertonungen von Kurt Weill und Ned Rorem zu hören sind, geben seine Eindrücke wieder – obgleich er im selben Atemzug eingestehen musste: „The real war will never get in the books.“

Das berühmte Gedicht O Captain! My Captain! sowie das George Crumbs Apparition zugrunde liegende When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d stellen hingegen eine direkte Reaktion auf die Ermordung Abraham Lincolns wenige Tage nach dem Ende des Krieges im Jahr 1865 dar.

Eine universelle Stimme

Trotz aller – manchmal grausamer – Konkretheit, die in Whitmans Gedichten und Texten begegnet, spricht aus ihnen stets eine universelle und unvergängliche Stimme, die den Schriftsteller nicht umsonst zum Wegbereiter der literarischen Moderne in Amerika werden ließ. Angesichts dessen ebenso wie der subtilen Musikalität seiner reimlosen Verse verwundert es nicht, dass Komponist:innen sich bis heute von seinen Schriften entzünden lassen. Ned Rorem ging sogar so weit, den Erfolg seiner 1969 uraufgeführten War Scenes gänzlich dem Dichter zuzuschreiben: „I’ve got to give Whitman the credit.“

Auch Kurt Weill, der 1935 in die USA emigriert war, mussten Whitmans Gedanken über den Krieg brandaktuell erscheinen. Beat! Beat! Drums! ist einerseits ein Aufruf an die gesamte Bevölkerung – Schulkinder, Mütter, Farmer, Händler, Anwälte, Wachende und Schlafende –, dem Kriegsgeschehen nicht tatenlos zuzuschauen; andererseits kommt darin die unentrinnbare Allgegenwart des Krieges zum Ausdruck, die sich bei Weill in unerbittlichen, marschartigen Rhythmen und durchdringenden Signalmotiven musikalisch niederschlägt. Völlig anders muten zwei weitere der insgesamt vier zwischen 1942 und 1947 entstandenen Whitman-Vertonungen des Komponisten an, O Captain! My Captain! und Come Up from the Fields, Father an. In letzterer folgt Weill der dramatischen Qualität des Textes und verzichtet auf motivische Geschlossenheit wie in Beat! Beat! Drums!. Stattdessen inszeniert er eine Abfolge verschiedener Szenen – Aufregung beim Eintreffen des Briefes, herbstliche Idylle der Landschaft, Benachrichtigung über die Kriegsverletzung des Sohnes, Schmerz und Klage der Mutter –, die in einem bittersüßen Hymnus kulminieren. Von klassischen Kompositionsmitteln bis zu Broadway-Anklängen vereint Weill in seiner Musik fast alles, was bis dato in seiner Laufbahn eine Rolle gespielt hatte. In eben dieser stilistischen Offenheit sah er die Ursache für die Anerkennung, die ihm auch im amerikanischen Exil zuteil wurde: „Mein Erfolg hier […] rührt vor allem aus der Tatsache, dass ich eine sehr positive und konstruktive Haltung gegenüber dem amerikanischen Lebensstil und den kulturellen Möglichkeiten dieses Landes einnahm, die von den meisten deutschen Intellektuellen, die gleichzeitig hier eintrafen, kritisch beäugt und bezweifelt wurden“, erklärte Weill rückblickend im Jahr 1949.

Unter den mehr als 500 Liedern des 1923 in Indiana geborenen Ned Rorem nehmen die War Scenes eine Sonderstellung ein. „Die Leute sagen mir oft, es sei das stärkste Stück, das ich je geschrieben habe. Jede Aufführung ist ein durchschlagender Erfolg“, bemerkte Rorem über den 1969 komponierten vierteiligen Zyklus, der den Opfern des Vietnamkrieges gewidmet ist. In den zugrundeliegenden Prosatexten aus Specimen Days – ursprünglich Tagebucheintragungen aus Whitmans Zeit als Krankenpfleger – zeigt sich für Rorem die zeitlose Wirkung des Autors: „Sie könnten sich auf den Trojanischen Krieg oder auf den Vietnamkrieg beziehen: Krieg ist immer sinnlos, und ich glaube, wenn dieser Zyklus überhaupt irgendeine Kraft hat, dann ist sie der Kraft Walt Whitmans geschuldet.“

Dass das Verhältnis zwischen Ned Rorem und seinem fünf Jahre älteren Landsmann Leonard Bernstein zeitweilig die Grenzen der Freundschaft überstieg, ist kein Geheimnis. Für Bernstein bedeutete die eigene homosexuelle Neigung einen lebenslangen inneren Zwiespalt: 1976 verließ er für mehrere Monate seine Frau, um mit einem Studenten zusammenzuleben. Im gleichen Jahr entstand sein Songfest. Anlässlich des zweihundertjährigen Bestehens der USA verleiht Bernstein darin 13 amerikanischen Dichter:innen das Wort, die sich verschiedenen Formen der gesellschaftlichen Ausgrenzung widmen. Walt Whitmans zutiefst persönliches, zu Lebzeiten unveröffentlichtes Gedicht To What You Said macht die Liebe zwischen Männern zum zentralen Thema. Bernstein fasst die Worte in einen nicht minder intimen, beinah hypnotischen, immerwährend um den Ton C kreisenden, elegischen Gesang. (Die Klavierversion des ursprünglich für großes Orchester instrumentierten Songfest stammt vom Komponisten selbst.)

Die Kräfte der Natur

Ähnlich kontemplativ im Tonfall gestaltet auch Frank Bridge die Musik zum Gedicht The Last Invocation, das den Moment des Übergangs in den Tod einfängt, wenn die Seele den Körper verlässt. Heute zu Unrecht kaum bekannt, war der Komponist, Bratschist, Dirigent und Lehrer von Benjamin Britten ein maßgeblicher Wegbereiter der Moderne in England.

Der in Glasgow geborene Komponist und Dirigent Oliver Knussen, seinerseits Britten-Schüler, widmet sich mit The Voice of the Rain einem Gedicht Whitmans, das im Rahmen des heutigen Programms auf einen weiteren thematischen Schwerpunkt im Werk des Autors verweist, wie er auch in Rorems Look Down, Fair Moon und vor allem George Crumbs Apparition zentral werden wird: die Natur und ihre symbolischen Bedeutungen. Regen – „der sanft fallende Schauer“ – erscheint als personifizierte Dichtung der Natur, der Knussen nach einer lautmalerischen Darstellung fallender Tropfen zu Beginn eine majestätische Stimme verleiht. Beiden gemein, Regen und Dichtung, sei ein ewiger Kreislauf von Aufsteigen, Transformieren, Absteigen, Leben geben und in Schönheit verwandeln.

An die Idee des ewigen Kreislaufs alles Lebenden knüpft Crumbs Liederzyklus Apparition inhaltlich nahtlos an. Klanglich eröffnet sich jedoch ein gänzlich neuer Raum: Sowohl der Klavier- als auch der Sopranpart fordern von den Interpretierenden eine radikale Erweiterung der traditionellen Palette – sei es durch Bespielung des Klaviers jenseits der Tasten, die Imitation von Vogelrufen oder „weiße Töne“ und geflüsterte Passagen im Gesang. Ausgangspunkt für diese sphärische – im Jahr 1979 mehr noch als heute die Kritik verstörende – Klangwelt bildet ein Ausschnitt aus Whitmans 16-strophiger Elegie When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d. Als Reaktion auf die Ermordung Abraham Lincolns entstanden, kreist der Text um den Schmerz über den erlittenen Verlust und den Tod in seiner universellen Bedeutung. Der Abschnitt Death Carol, der fünf von insgesamt sechs Liedern (ausgenommen die drei textlosen Vokalisen) zugrunde liegt, stellt den letztlich Erlösung versprechenden Gesang einer Drossel dar, die hier sinnbildlich für den Tod steht. (Bereits in Paul Hindemiths O, nun heb du an, dort in deinem Moor von 1919, dem eine Strophe aus dem gleichen Gedicht zugrunde liegt, tritt der scheue, vor allem nachts in sumpfigen Gegenden Nordamerikas singende Vogel in dieser Bedeutung auf.)

Nur das zweite Lied When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d entstammt einem anderen Abschnitt des gleichnamigen Gedichts. Der Duft von blühendem Flieder, wie Whitman ihn an Lincolns Todestag atmete, sollte für ihn untrennbar mit diesem Ereignis verbunden bleiben. George Crumb wiederum vermochte die geheime Macht der Musik so kunstvoll zu lenken, dass an dieser Stelle tatsächlich die Illusion eines solchen Duftes entsteht. Dem entspricht Crumbs Auffassung: „Ich habe Musik immer als eine sehr merkwürdige Substanz betrachtet, eine Substanz, die mit magischen Eigenschaften ausgestattet ist“. In einem Flusstal der Appalachen geboren, ist Crumb außerdem überzeugt, dass „jeder Komponist von Kindesbeinen an eine ‚natürliche Akustik‘ erworben hat, die ein Leben lang im Ohr bleibt.“ Bestimmte Echowirkungen gehörten dadurch zur Grundlage seines Klangspektrums – wie vor allem das erste Lied in seiner naturnahen Geräuschhaftigkeit bezeugt. Wenn es am Ende des Zyklus’ nach ekstatischen Ausbrüchen und jubelnder Versöhnung mit dem Tod beinah identisch wiederkehrt, erfüllt sich der ewige Kreislauf. Was zurückbleibt, sind die Kräfte der Natur.

Meike Pfister lebt als Pianistin, Musikwissenschaftlerin und Moderatorin in Berlin und ist hauptsächlich an der Universität der Künste und der Philharmonie Berlin sowie an der Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg tätig.

The Artists

Claron McFadden

Soprano

American soprano Claron McFadden studied at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, and has lived in the Netherlands since 1984. She made her operatic debut at the 1985 Holland Festival in Johann Adolph Hasse’s L’eroe cinese, conducted by Ton Koopman. The following year, she first collaborated with William Christie in a production of Rameau’s Anacréon at the Opéra Lyrique du Rhin, which launched a close artistic partnership that has endured ever since. The two artists have performed together in the U.S., South America, and throughout Europe, including at the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence (Rameau’s Les Indes galantes) and at London’s Royal Opera House (Purcell’s King Arthur). Claron McFadden has made guest appearances at many major opera houses, including the Dutch National Opera, Teatro La Fenice in Venice, Munich’s Bavarian State Opera, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, and Opéra de Lyon, at the festivals of Salzburg, Glyndebourne, and Tanglewood, and with leading orchestras such as the Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Philharmonic, BBC Symphony, Germany’s MDR, SWR, and WDR radio symphony orchestras, Ensemble intercontemporain, and Klangforum Wien. Together with the Arditti Quartet, she gave the world premiere of Wolfgang Rihm’s Akt und Tag. In 2020, Claron McFadden was appointed Knight of the Order of Orange-Nassau by King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands.

December 2023

Julius Drake

Piano

As a pianist and lied accompanist, Julius Drake regularly appears in the world’s major music centers, including the festivals of Aldeburgh, Edinburgh, Salzburg, Munich, Schwarzenberg, and Oxford, New York’s Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, the Berlin Philharmonie, Milan’s La Scala, Konzerthaus and Musikverein in Vienna, and London’s Wigmore Hall. Among his regular collaborators are singers such as Sir Thomas Allen, Ian Bostridge, Iestyn Davies, Joyce DiDonato, Gerald Finley, Simon Keenlyside, Angelika Kirchschlager, Julia Kleiter, Dame Felicity Lott, and Christoph Prégardien. He has curated lied series for Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, and the BBC, and at London’s Middle Temple Hall performs an annual recital series, “Julius Drake and Friends.” Director of the Perth International Chamber Music Festival from 2000 to 2003, he served as artistic director of the Leeds Lieder festival in 2009 and that same year was appointed artistic director of the Machynlleth Festival in Wales. Julius Drake holds professorships at the University of Arts in Graz and at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama. At the Pierre Boulez Saal, he has since 2021 curated the series Lied und Lyrik, which presents the works of selected poets opposite musical settings from different eras.

December 2023

Toby Jones

Recitation

British actor Toby Jones has been acclaimed for his performances on stage and on screen for more than three decades. After training at Manchester University and with Jacques Lecoq in Paris, he first gained stage experience with his own theater company, performing at festivals around the world, in guest engagements in repertory theater, and, in 1996, as the first artist in residence at the West Yorkshire Playhouse. He made his West End debut in 2001 in Kenneth Branagh’s production of The Play What I Wrote, for which he received the Olivier Award for Best Supporting Actor. In 2020, he returned to the West End in the title role in Conor McPherson’s adaptation of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. He has also appeared regularly at the National Theatre, Almeida Theatre, and Royal Court Theatre, among others. His most recent films include Empire of Light, The Wonder, Tetris, and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. Other work for the big screen includes Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Berberian Sound Studio, The Mist, Dad’s Army, Journey’s End, The Hunger Games, Frost/Nixon, and the first two Captain America films. In the Harry Potter film series, Toby Jones voiced the role of Dobby the House-elf. His best known roles on television include Lance Stater in Mackenzie Crook’s series Detectorists, for which he was awarded a BAFTA. In 2021, Toby Jones was made an Officer of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II.

December 2023