María Dueñas Violin

Alexander Malofeev Piano

Program

Karol Szymanowski

Sonata for Violin and Piano in D minor Op. 9

Gabriela Ortiz

De Cuerda y Madera – Capriccio a dos for Violin and Piano

German Premiere

César Franck

Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major

Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937)

Sonata for Violin and Piano in D minor Op. 9 (1904)

I. Allegro moderato

II. Andantino tranquillo e dolce – Scherzando – Tempo I

III. Finale. Allegro molto, quasi presto

Gabriela Ortiz (*1964)

De Cuerda y Madera – Capriccio a dos for Violin and Piano (2024)

German Premiere

Intermission

César Franck (1822–1890)

Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major (1886)

I. Allegretto ben moderato

II. Allegro

III. Recitativo-Fantasia. Ben moderato

IV. Allegretto poco mosso

Encores

Franz von Vecsey

Valse triste

Astor Piazzolla

Yo soy María

(from María de Buenos Aires)

Claude Debussy

Beau soir

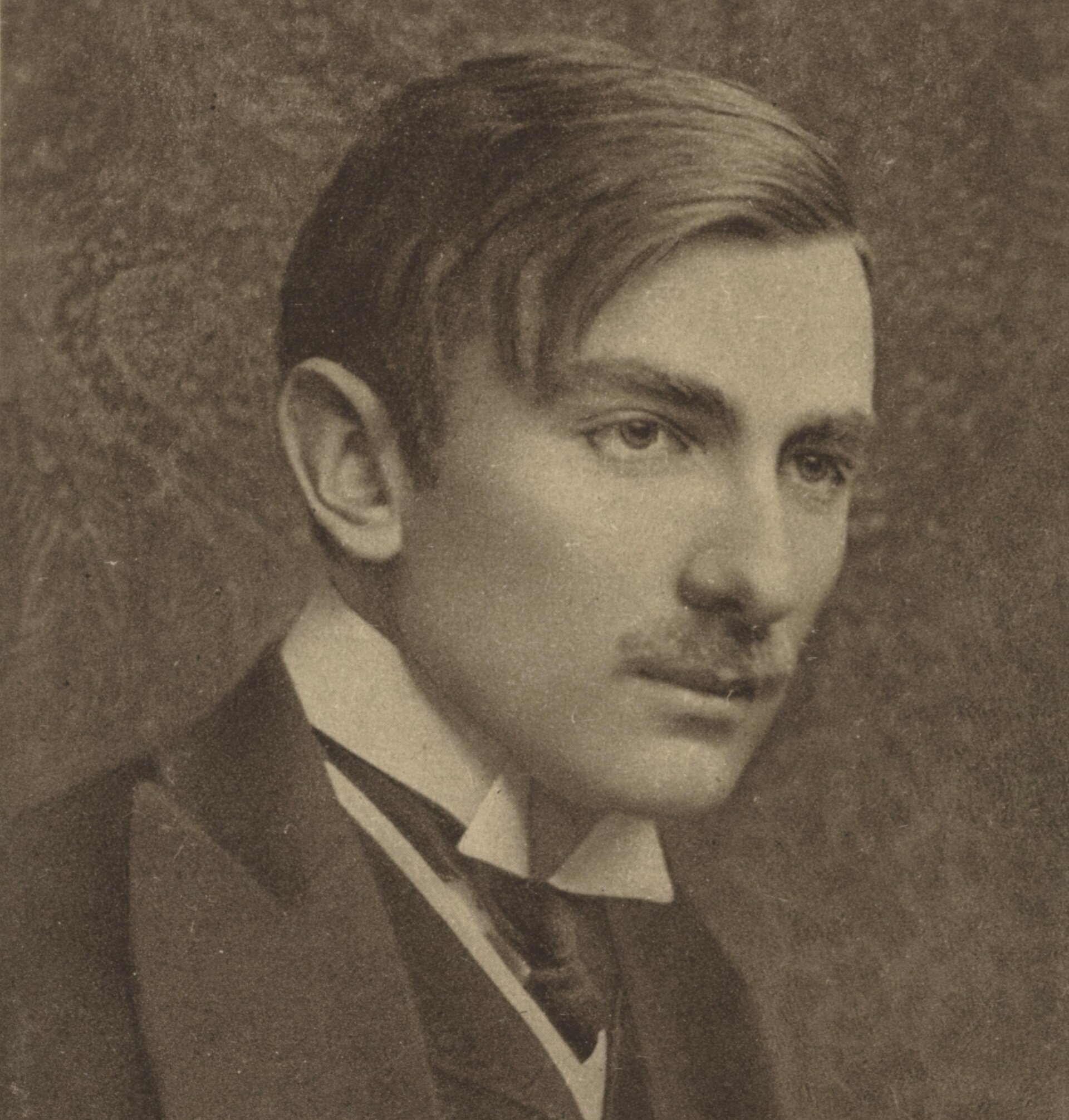

Karol Szymanowski, c. 1912–18

String and Wood and Heart

For their joint Pierre Boulez Saal debut, María Dueñas and Alexander Malofeev have chosen a famous and an unknown violin sonata—and introduce Mexican composer Gabriela Ortiz’s De Cuerda y Madera, which is dedicated to Dueñas.

Essay by Gavin Plumley

String and Wood and Heart

Music for Violin and Piano

Gavin Plumley

Young Poland

A hierarchy endures within the telling of the history of fin-de-siècle Europe. Its lodestars are belle époque Paris, Oscar Wilde’s London, and the Secessionist hubs of Munich, Berlin, and Vienna. Yet around these centers orbit other significant satellites, including Warsaw. Nonetheless, the precarity of Polish nationalism, due to pressures from neighboring empires, leant a febrile quality to its statements of patriotic faith at the turn of the last century. They included those of a cultural hue, emerging largely from the “Young Poland” movement.

Born near what is now Kropyvnytskyi in Ukraine, Karol Szymanowski was to become one of the most prominent members of the group when he moved to Warsaw in 1901 to take lessons with Marek Zawirski, a professor at the city’s Music Institute. The advent of the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and an unbridled love for Richard Strauss, as well as a keen belief in art for art’s sake and the preservation of Chopin’s flame, all combined in Szymanowski’s early work. Backed by Prince Władysław Lubomirski, the composer made his way to prominence both at home and abroad, encompassing periods in Vienna—and the acceptance of a contract from Universal Edition—and his inspirational trips to Sicily and, later, North Africa. Together, these helped widen Szymanowski’s knowledge and sphere of influence significantly, eventually leading to the creation of the opera King Roger and other richly idiosyncratic masterpieces.

The 1904 Violin Sonata in D minor is an apprentice work, written when Szymanowski was just 21. Completed shortly before the Warsaw Philharmonic mounted a concert of various new works by Young Poland composers, it is nonetheless imbued with significant maturity. The score was dedicated to Bronisław Gromadzki, an amateur violinist and close friend, but had to wait several years to be heard in public. Eventually, Paweł Kochański (later known as Paul Kochanski) and Arthur Rubinstein gave the premiere in Warsaw in April 1909.

What they revealed was a work of stirring if, occasionally, stuttering intent. Conceived in the shadow of Strauss’s and Franck’s sole sonatas—the latter also performed this evening—it is cast in three movements with subtly recurring themes. The piano textures, on the other hand, teeter on the orchestral in their sheer force and richness, even looking to Scriabin’s monumental style. The result, with a tonal but highly chromatic harmonic palette, is a work that embraces both the impetuousness of youth and the tender, bruised introspection that was to become the hallmark of Szymanowski’s richest creations.

The second movement, marked “Andantino tranquillo e dolce,” may well be the highlight of the whole, eschewing expectations and allowing the musical voice simply to speak—and be heard—as well as providing a surprising scherzando excursion. While some of the balder elements of Szymanowski’s response to the sonata genre, including the first movement’s unembroidered recapitulation, may pale in comparison to his models, there can be no denying the thrill of the tarantella finale. Little wonder Kochański was to remain a keen supporter of Szymanowski’s work, with the violinist’s advocacy soon repaid by the composition of not one but two violin concertos.

Contrast and Repose

The recipient of the National Prize for Arts and Literature and the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and Fulbright-García Robles Fellowships, Gabriela Ortiz is “one of the most talented composers in the world,” according to her longtime collaborator Gustavo Dudamel. Born in Mexico City, her parents were among the founding members of Los Folkloristas, a well-known music ensemble dedicated to Latin American folk music.

Her own musical education began along similar lines, when she played the charango and guitar with her mother and father, but Ortiz also began to learn classical piano and studied composition with Mexican composers such as Mario Lavista, Julio Estrada, Federico Ibarra, and Daniel Catán. She then continued her studies in Europe, including electronic music at City University in London, before going on to create an increasingly diverse catalogue that remains true to her roots while speaking to a much wider audience. Dudamel’s advocacy, including the premieres of a new ballet, Revolución Diamantina, and Dzonot for cellist Alisa Weilerstein and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, as well as performances by many other leading orchestras, have helped ensure the success of her vision.

Among Ortitz’s more recent works is the violin concerto Altar de Cuerda, also first heard in Los Angeles in 2022. Marking the seventh in a series of “altar” pieces, in which the composer avoids specifically religious fervor in favor of much broader spirituality, Altar de Cuerda not only garnered wide critical acclaim but also cemented Ortiz’s working relationship with María Dueñas (who made the recording with Dudamel). Yet just as the composer’s “altar” series is an ongoing concern, so is the inspiration the violinist supplied when performing the concerto, as Ortiz herself explains:

“After writing my first concerto for violin and orchestra Altar de Cuerda, dedicated to the talented violinist María Dueñas, the idea arose at her request to write a new piece for violin and piano as a musical capriccio. This is how De Cuerda y Madera [‘Of String and Wood’] was born, a playful and eclectic piece that develops in a free way using the violin and the piano in a constant dialogue of high musical virtuosity.

“The work is divided into three sections: two of them (first and last) of a fast and lively nature, based on ideas that somehow arise from Afro-Caribbean or folkloric music. In the central part there is a small section of a slower and more cantabile character that serves as a musical contrast and repose. In the third section I decided to add a small cadenza for the violin, which is slightly accentuated with some piano interventions, and which prepares the final coda. The piece is dedicated to María Dueñas who was the total inspiration for writing this music.”

First heard at the Angelika Kauffmann Saal in Schwarzenberg, Austria, last Saturday, the work receives its second public performance—and German premiere—tonight. The U.S. premiere will then follow at Carnegie Hall in a week’s time, as part of a season-long focus on Ortiz’s work.

Intensity in the Twilight

We can hope that the early performances of De Cuerda y Madera will prove somewhat simpler than initial outings of César Franck’s Violin Sonata, written in 1886. It was conceived as a wedding present for violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, one of the Belgian composer’s cherished “bande” of musicians. A play-through of the Sonata took place at the marriage itself, in September 1886, though Franck was sadly absent from the festivities. An official premiere then followed a few months later, albeit on a dark winter afternoon in the unlit Musée des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Ysaÿe and his pianist, Marie-Léontine Bordes-Pène, had not quite reached Franck’s work, the final piece on the program, by the time the light failed. They were therefore forced to play the first movement much faster than the specified marking and, by the end of the Sonata, with the room as black as night, were performing from memory.

Despite these trying circumstances, it was, by all accounts—including that of composer Vincent d’Indy—an extraordinary event, unfolding with “mystic intensity” in the “winter twilight.” So impressed was Franck that he even adopted the performers’ tempo marking in the first movement when it came to publication. Yet the Allegretto is crucial for other reasons too, in that the Sonata’s entire material derives from the yearning intervals that open the work. Indeed, this section is conceived as an introduction to the whole, a sort of wellspring from which the remaining movements draw their motifs.

Following its wistful music and scudding modulations, passions left (nearly) unspoken, the Allegro turns the Allegretto’s gestures—all revolving around a third—into a much more rapid, even torrid stream that shifts constantly from D minor to D major. Throughout, however, the more plangent tones of the first movement resurface, the sense of melancholy keeping the second movement’s outspoken anger (and premature lust for triumph) in check.

The tonality of that commotion is presented again at the beginning of the Recitativo-Fantasia, featuring both recollections of what has gone before and new melodies from old motifs at its key-changing close. Such a vision befits the movement’s freer form but likewise turns the focus to the end of the Sonata. For if the work can appear somewhat front-loaded in its motivic resourcefulness, Franck defies any such reading due to the amazing display in the finale. Here, he not only presents two versions of the basic material in canon—said to represent the relationship between Ysaÿe and his new wife—but he also incorporates melodies from the third movement before tying all the different strands together at the Sonata’s exultant close.

Gavin Plumley is a cultural historian. British by birth, his work embraces various aspects of Central European art, music, and literature. He has written for newspapers and magazines, as well as opera and concert programs, worldwide. He also broadcasts regularly for the BBC. His first book, A Home for All Seasons, was published in 2022.

Gabriela Ortiz (© Marta Arteaga)

Musikalische Dialoge

César Francks Violinsonate zählt zu den Klassikern des Duorepertoires. María Dueñas und Alexander Malofeev stellen sie einem selten zu hörenden Jugendwerk Karol Szymanowskis und einer neuen Komposition der Mexikanerin Gabriela Ortiz gegenüber.

Essay von Michael Horst

Musikalische Dialoge

Werke für Violine und Klavier

Michael Horst

Leidenschaftliches Jugendwerk

Karol Szymanowskis Violinsonate d-moll

„Da war er: ein großer, schlanker Mann. Er sah älter aus als seine 21 Jahre, ganz in schwarzer Trauerkleidung, mit Melone und Handschuhen – seine Erscheinung war eher die eines Diplomaten als die eines Musikers. Doch seine wunderschönen graublauen Augen hatten einen traurigen, intelligenten und sehr sensiblen Ausdruck.“ So erinnerte sich, viele Jahrzehnte später, der Pianist Arthur Rubinstein an die erste Begegnung mit Karol Szymanowski (dessen Vater kurz zuvor gestorben war). Aus diesem Zusammentreffen sollte sich eine lebenslange Freundschaft der beiden polnischen Musiker entwickeln, die bis zum Tod Szymanowskis im Jahr 1937 andauerte. Mehr noch: Rubinstein, schon in jungen Jahren zu einem gefeierten Pianisten aufgestiegen, setzte sich immer wieder für die Musik des Freundes ein. Er war es auch, der gemeinsam mit dem Geiger Pavel Kochánski 1909 dessen Violinsonate d-moll op. 9 in Warschau zur Uraufführung brachte. Kochánski blieb ebenfalls Zeit seines Lebens eng mit dem Komponisten verbunden, der für ihn in späteren Jahren u.a. seine beiden Violinkonzerte schrieb.

Zur Zeit der Begegnung mit Rubinstein stand Szymanowski ganz am Anfang seiner Karriere, und es war kaum abzusehen, dass er zum bedeutendsten Komponisten seines Landes nach Frédéric Chopin werden sollte. Doch die Vorzeichen waren günstig: Denn die begüterte und kunstsinnige Familie ermöglichte dem jungen Karol früh eine musikalische Ausbildung. Der Besuch einer Aufführung von Lohengrin in Wien wurde dann für den 13-Jährigen zum Erweckungserlebnis. Neben Wagner fanden Brahms und Reger genauso Interesse, und der Studienfreund Ludomir Rózicky erinnerte sich später, wie er gemeinsam mit Szymanowski am Konservatorium in Warschau voller Begeisterung die seinerzeit hochmodernen symphonischen Dichtungen von Richard Strauss vierhändig am Klavier gespielt hatte. Andererseits war das Komponieren von Klaviermusik für einen jungen Polen ohne den Blick auf Chopin undenkbar – dessen Werk hat Szymanowski in der Tat in jenen Jahren ebenfalls intensiv studiert.

Kein Wunder also, dass sich vielerlei musikalische Einflüsse in der Violinsonate des 21-Jährigen finden. Dabei ist die Moll-Tonart – vorherrschend in all seinen frühen Werken – einem melancholischen Gestus geschuldet, den der Komponist gerade in jungen Jahren mit großer Hingabe pflegte. Auch in der Sonate fallen Vortragsangaben wie „passionato“ und „patetico“ auf, zusammen mit einer sehnsuchtsvollen Chromatik, die bereits das Anfangsthema prägt – Szymanowski hat seinen Wagner hörbar verinnerlicht. Anderseits wäre dieses Stück ohne das Vorbild der Violinsonate von César Franck – heute im zweiten Konzertteil zu hören – kaum denkbar. Immer wieder flicht Szymanowski rezitativische Passagen für die Violine ein, um sie dann wieder in kantablen Bögen schwelgen oder in leidenschaftlichen Ausbrüchen romantische Emotionen evozieren zu lassen.

Den musikalischen Ruhe- und Mittelpunkt der Sonate bildet das Andante tranquillo, dessen schlichte Melodie von mannigfachen Arabesken im Stil Chopins umspielt wird. Wieder baut Szymanowski mehrfach kleine Kadenzen für die Violine ein, die das improvisatorische Moment der Musik betonen. Unterbrochen wird das Andante – hier könnte Brahms mit seiner A-Dur-Violinsonate Vorbild gewesen sein – von einem Scherzo-Abschnitt mit aparten Pizzicato-Akkorden. Ebenfalls an Brahms erinnert das im furiosen Sechsachteltakt voranstürmende Finale, in dem sich Violine und Klavier gegenseitig in chromatischen Wellenbewegungen aufschaukeln. Dramatische Tremoli sorgen für zusätzliche Spannung, bevor der Übergang nach D-Dur und die Reminiszenz an das melodische Seitenthema des ersten Satzes für schwelgerische, lichtdurchflutete Schlusstakte sorgen.

Virtuosität und Rhythmik

Gabriela Ortiz’ De Cuerda y Madera

Hierzulande ist die Musik der Komponistin Gabriela Ortiz bislang noch eher selten zu hören, doch auf dem amerikanischen Kontinent hat die Karriere der Mexikanerin zuletzt deutlich Fahrt aufgenommen; vor allem Gustavo Dudamel hat durch die Uraufführung mehrerer Werke wie Antrópolis (2019) und Kauyumari (2021) mit dem Los Angeles Philharmonic viel zu ihrem Erfolg beigetragen. Über ihre 2017 entstandene Komposition Téenek, die er im vergangenen Jahr auch bei den Berliner Philharmonikern dirigierte, sagt Dudamel: „Farbe, Textur, Harmonik und die allem zugrundeliegende Rhythmik sind einzigartig. Gabriela besitzt eine besondere Fähigkeit, unsere lateinamerikanische Identität zu zeigen.“ In dieser Saison ist Ortiz Composer in Residence an der Carnegie Hall, und erst jüngst widmete die New York Times ihr ein ausführliches Portrait, in dem sie als prominente Stimme für einen Paradigmenwechsel in der klassischen Musik gewürdigt wird, im Zuge dessen endlich auch Werke lateinamerikanischer Komponist:innen stärker im Fokus des Konzertlebens stehen.

In stilistischer Hinsicht überschreitet Gabriela Ortiz gern Grenzen – zwischen Folklore und Jazz, klassischem Instrumentarium und elektroakustischen Effekten. Neben zahlreichen Orchesterwerken schuf sie Ballett- und Filmmusik, darüber hinaus hat sie in mehreren Opern aktuelle und politische Fragen auf die Bühne gebracht, so das Thema Drogenkrieg in Unicamenente la verdad (2010) und die illegale Migration von Mexiko in die USA in Ana y su Sombra (2013).

Ihr jüngstes Kammermusikwerk De Cuerda y Madera („Von Saite und Holz“), vor wenigen Tagen im österreichischen Schwarzenberg uraufgeführt, entstand für María Dueñas; ihr ist das Werk auch gewidmet. Ortiz selbst spricht von einem „musikalischen Capriccio“, einem „spielerisch-eklektischen Stück“, in dem die Virtuosität im Dialog zwischen Violine und Klavier einen besonderen Stellenwerk genieße. Dabei ist das zehnminütige Werk ganz klassisch in drei Abschnitte gegliedert – in den schnellen Außenteilen dominieren afro-karibische Anklänge, die sich aus einem dichten Klangteppich nach und nach herausschälen. Ein stark rhythmisches Element durchzieht die ganze Partitur, wird im langsamen Mittelabschnitt noch intensiviert und bestimmt auch im Sechsachteltakt stehenden Schlussteil. Kadenzartige Abschnitte bieten der Violine mehrfach Raum für solistische Entfaltung. Mit einer rasanten Stretta endet das Stück.

Kontrapunktische und melodische Meisterschaft

César Francks Violinsonate A-Dur

Nur knapp zwei Jahrzehnte vor Szymanowski schrieb der aus dem belgischen Lüttich stammende und seit seinem 13. Lebensjahr in Paris beheimatete César Franck seine Violinsonate A-Dur. Lange Zeit hatte Kammermusik in Frankreich neben der allgegenwärtigen Oper ein Schattendasein geführt. Im Zuge eines mit dem Deutsch-Französischen Krieg neu erwachten Nationalgefühls führte erst die maßgeblich von Camille Saint-Saens angeregte Gründung der Société nationale de musique 1871 zu einer bewussten Neuorientierung – und Franck, Organist an einer der führenden Kirchen von Paris, zählte zu den Mitstreitern der ersten Stunde. Francks Violinsonate entstand nach Vorgängerwerken von Gabriel Fauré (1875/76) und Saint-Saëns (1885) im Jahr 1886 als Hochzeitsgeschenk für seinen Landsmann Eugène Ysaÿe, damals 28 Jahre alt und am Beginn einer großen internationalen Karriere, der dem Werk schnell zum Durchbruch verhalf.

Francks letztes Lebensjahrzehnt – er starb vier Jahre nach Komposition der Violinsonate – war das fruchtbarste seiner gesamten Laufbahn, gekrönt von der d-moll-Symphonie und den Symphonischen Variationen für Klavier und Orchester. Musikalische Reife und Erfahrung begegnen in diesen Werken einem innovativem Zugriff. Im Fall der A-Dur-Sonate dürfte einerseits die barocke Kirchensonate mit ihrer Satzfolge von langsam – schnell – langsam – schnell Pate gestanden haben; gleichermaßen ist die kontrapunktische Meisterschaft des Organisten Franck eine tragende Säule des Werks. Andererseits machte sich der Komponist auch die neuesten Ideen der Wagner-Liszt-Schule zunutze, indem er das leitmotivische Denken aus Oper und symphonischer Dichtung auf die Kammermusik übertrug.

Das zyklische Prinzip trägt das gesamte Werk: Thematische Querverweise über die Sätze hinweg finden sich immer wieder, direkt wie indirekt. Schon der Dominant-Nonen-Akkord des Klaviers zu Beginn öffnet wie ein Vorhang den Zugang zu einem ganzen lyrischen Kosmos; er wird in seinem Terzaufbau, in immer wieder neuen Verwandlungen, auch zum zentralen gestalterischen Moment der Sonate. Insbesondere in harmonischer Hinsicht kostet Franck alle spätromantischen Möglichkeiten aus, indem er die chromatischen Wanderungen durch die Tonarten auf kleinste Räume fokussiert und damit eine enorme Binnenspannung innerhalb der Musik schafft. Ebenso zeigt sich in den rhapsodischen Steigerungen, die sich immer wieder in weitgeschwungene Kantilenen der Violine auflösen, die gestalterische Souveränität des Komponisten.

Der klare Formplan, der jedem einzelnen Satz wiederum ganz unterschiedliche Einzelabschnitte zuordnet, sticht besonders im mit „Recitativo – Fantasia“ überschriebenen dritten Satz heraus: Franck lässt ihn im Stil einer großen Soloszene für die Violine beginnen, um nach und nach beide Instrumente enger zu verschränken und die Musik schließlich wie in eine Arie münden zu lassen, die wiederum der Violine, von sanften Triolen im Klavier begleitet, breiten Raum für ausdrucksvolle Melodiebögen gibt. Doch der Fortissimo-Höhepunkt bringt noch nicht den Abschluss – die Violine zieht sich wieder rezitativisch zurück. Von ganz besonderer Eigenart ist das Finale, in dem Franck seine kontrapunktischen Fähigkeiten in einem veritablen Kanon vorführt, wobei wuchtige Klavierbässe eine zusätzliche Orgelstimme simulieren. Im Mittelteil greift der Komponist noch einmal auf das ariose Material des vorangegangenen Satzes zurück, um schließlich dem Kanon-Thema das letzte Wort zu geben, das in Engführung und kompakter Akkordik – man fühlt sich an das „volle Werk“ einer großen Orgel erinnert – die Sonate zu einem klangvollen Abschluss bringt.

Der Berliner Musikjournalist Michael Horst arbeitet als Autor und Kritiker für Zeitungen, Radio und Fachmagazine. Außerdem gibt er Konzerteinführungen. Er publizierte Opernführer über Puccinis Tosca und Turandot und übersetzte Bücher von Riccardo Muti und Riccardo Chailly aus dem Italienischen.

The Artists

María Dueñas

Violin

Spanish violinist María Dueñas enchants audiences with the breathtaking array of color she conjures from her instrument. Her technical skill, artistic maturity, and bold interpretations have won her rave reviews and invitations from the world’s greatest orchestras and conductors. Born in Granada in 2001, she was accepted to join the conservatory of her hometown at the age of seven. Since 2016, she has been studying with Boris Kuschnir at the Music and Arts University of the City of Vienna, where she lives. Following a string of first-prize wins at major international competitions, she is in demand around the world and performs with leading orchestras such as the Pittsburgh Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Staatskapelle Berlin, and NHK Symphony Orchestra, collaborating with conductors including Manfred Honeck, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Marek Janowski, Daniel Harding, Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Kent Nagano, and Herbert Blomstedt. She has enjoyed a particularly close association with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel. She released her first album Beethoven and Beyond with Manfred Honeck and the Vienna Symphony in 2023. María Dueñas plays the 17?4 Nicolò Gagliano violin, on loan from Deutsche Stiftung Musikleben, and the 1710 “Camposelice” Stradivari, provided to her by the Nippon Music Foundation.

© KünstlerSekretariat am Gasteig / September 2024

Alexander Malofeev

Piano

Born in Moscow in 2001, Alexander Malofeev has been among the most promising pianists of his generation since winning the International Tchaikovsky Competition for Young Musicians in 2014. He has performed with leading orchestras such as the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, the Korean Symphony Orchestra, and the Verbier Festival Chamber Orchestra, collaborating with Mikhail Pletnev, Susanna Mälkki, Fabio Luisi, Alondra de la Parra, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin, among many others. He has also appeared at the festivals of La Roque d’Anthéron, Tanglewood, Aspen, and Rheingau. This season, he will be heard with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, and the San Diego Symphony Orchestra, among others, as well as at the Verbier Festival, the Chamber Music Hall of the Berlin Philharmonie, and on tour in the U.S. and Asia. Alexander Malofeev lives in Berlin.

October 2024