Yun-Peng Zhao Violin

Léo Marillier Violin

Franck Chevalier Viola

Alexis Descharmes Violoncello

Program

György Ligeti (1923–2006)

String Quartet No. 1 Métamorphoses nocturnes (1953–54)

Helmut Lachenmann (*1935)

String Quartet No. 3 Grido (2001)

Intermission

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

String Quartet No. 2 in A minor Op. 51 No. 2 (1873)

I. Allegro non troppo

II. Andante moderato

III. Quasi Minuetto, moderato – Allegretto vivace – Tempo I

IV. Finale. Allegro non assai

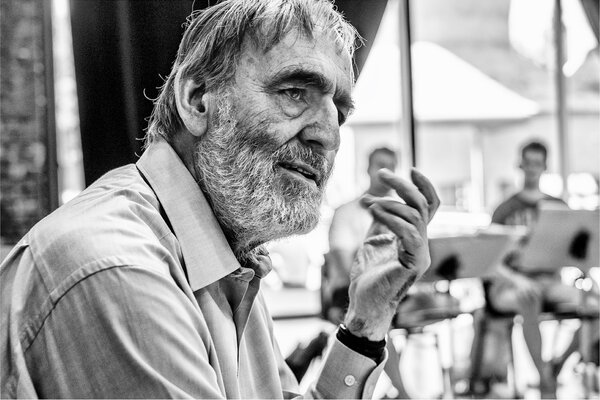

Helmut Lachenmann, 2013 (© Emilio Pomarico)

Creative Frictions

Helmut Lachenmann outlined the essential challenges of writing music at the time of the premiere of his Third String Quartet in 2001. “For me,” he explained, “composing means, if not ‘solving a problem,’ then indeed ecstatically grappling with a traumatic dilemma: to confront the technical challenges of composition—perceived and adopted—so as to bring about a resolution.” In different times and in different circumstances, György Ligeti and Johannes Brahms likewise grappled with that task, of finding new solutions, not least in the face of the resolve of those who went before them.

Program Note by Gavin Plumley

Creative Frictions

String Quartets by Ligeti, Lachenmann, and Brahms

Gavin Plumley

Helmut Lachenmann outlined the essential challenges of writing music at the time of the premiere of his Third String Quartet in 2001. “For me,” he explained, “composing means, if not ‘solving a problem,’ then indeed ecstatically grappling with a traumatic dilemma: to confront the technical challenges of composition—perceived and adopted—so as to bring about a resolution.” In different times and in different circumstances, György Ligeti and Johannes Brahms likewise grappled with that task, of finding new solutions, not least in the face of the resolve of those who went before them.

A Personal Work

The first performance of Ligeti’s Métamorphoses nocturnes, on May 8, 1958 at the Musikverein in Vienna, was somewhat belated. The work had been written in Hungary in 1953–4, during a brief period of relaxation in post-war politics in Ligeti’s homeland. Come the 1956 Revolution, however, Ligeti was forced to flee, taking to the Austrian capital those compositions he felt were truly important, including his First Quartet. In truth, the score would never have seen the light of day had he remained in Budapest, given the regime’s determined censorship of what it considered modernism.

The work is, in many ways, an homage. György Kurtág called it “Bartók’s Seventh String Quartet,” while Ligeti himself remarked that “the piece still belongs firmly to the Bartók tradition … yet despite the Bartók-like tone (especially in rhythm) and some touches of Stravinsky and Alban Berg, I trust that the First String Quartet is still a personal work.” It need not be a case of either/or. For while the ruminatory music with which the Quartet opens harks back to the pensive counterpoint and nocturnal passages of Bartók’s six contributions to the genre, to say nothing of the playing techniques and the juxtaposition of fast and slow movements in an arch-like structure—even the marking of “mesto” (sad) in the third of its 17 interlinked sections—the rhythmic wit is Ligeti’s own. So too is his response to variation form: “There is no specific ‘theme’ that is varied. It is, rather, that one and the same musical concept appears in constantly new forms—that is why ‘métamorphoses’ is more appropriate than ‘variations.’ The Quartet can be considered as having just one movement or also as a sequence of many short movements that melt into one another without pause or which abruptly cut one another off.”

For the sense of homage to Bartók and, indeed, mourning the events of the early 1950s, Ligeti was looking beyond. The dense clusters of 1961’s Atmosphères are just around the corner, as well as even broader musical horizons.

Crusoe’s Question

Lachenmann’s landscape is no less diverse, with its extraordinary variations in texture and terrain. Initially, during studies in his native Stuttgart, as well as in Venice (with Nono) and at Darmstadt, there were comparative traces of the Second Viennese School, even previous benchmarks, such as in the piano cycle Fünf Variationen über ein Thema von Franz Schubert (1956–7). Often, these seemingly backward-looking glances were made more as a point of distinction than resemblance—Brahms does the same in the Quartet that closes tonight’s program—yet an even greater sense of individuality would emerge at the end of the 1960s in what Lachenmann called his musique concrète instrumentale.

Compelling and exacting in its sonorities, this was music that avoided traditional instrumental methods; to offer unexplored sound worlds untarnished by the past. Violent, controversial, Lachenmann’s works were often construed as acts of disavowal at the time, yet he continued to engage with established genres, including three string quartets, which adumbrate the composer’s shifting views. In the first (1972), subtitled Gran Torso, he “effectively made a 16-stringed instrumental body which reacted to maltreatment with its corporeality—sounding, rustling, breathing, pressing,” thereby turning “concrete energy into sound production.” Nearly 18 years later, Lachenmann returned to the genre and “focused on a single, developed playing technique: the ‘pressureless flautando,’ in which notes function more like shadows of sound.”

Although he felt that, in writing these two works, as well as the Tanzsuite mit Deutschlandlied (1980)—“a kind of concerto for string quartet and orchestra”—he “had overcome the ‘trauma’ associated with the string quartet,” Lachenmann’s search for authenticity remained. And it was one that would prompt a sense of crisis, “because of music’s ubiquity and ready availability.”

“What does Robinson Crusoe do if he believes his island to be developed? Does he settle down anew, returning in a self-established ambience to the lifestyle of bourgeois contentment? Should he heroically tear down the establishment again? Should he leave his nest? For he who seeks the way, what is one to do once the path through the impassable has been trodden? He reveals himself and writes his Third String Quartet, because the appearance of self-satisfaction is deceptive. Pathways in art don’t lead anywhere and most certainly not to a destination. For this goal is nowhere else but here—where friction between the creative will and its processes turns the familiar into the foreign—and we are blind and deaf.”

In 2001, the composer revealed that response: Grido. Meaning a shout or cry in Italian, the work’s subtitle likewise encoded a dedication to the members of the Arditti Quartet, spelling out an acronym that comprised the first letters of their names.

“A louder piece than my two previous quartets,” the published score is preceded by extensive “Notes on Performance and Notation.” The opening section deals with “general remarks,” including the use of wooden mutes, pressed bow actions, alternative clefs, and dampening grips, while a more extensive second section describes “playing techniques,” including what Lachenmann terms “gasping.” Used throughout, it takes the form of a forceful crescendo, cut off so abruptly that it leaves a gasp, “like a recording of a pizzicato played backwards.”

Evanescent too in its use of harmonics, the music is nonetheless punctured by insistent triplet figurations that seek to ground an otherwise febrile texture. Occasionally, the sound is so thin, denying itself, that it is barely present. We are therefore invited to lean forward, only to find ourselves attacked by contrasting acts of insistence. Harmonic coalescence similarly cajoles and taunts, and while, at times, we imagine the brittle beauty of a celesta, it is only to forestall creaking violence. And yet the loudest extremities of this work are not its most terrifying; by its close, we do indeed begin to doubt whether we can see or hear at all.

Contrasting Feints

Johannes Brahms’s struggle with the string quartet was no less existential. As with the symphony, he was forced to wrestle with Beethoven—or, rather, the mythology that surrounded him. And so, like the First Symphony, the First String Quartet, in the same characteristic key of C minor, sat on Brahms’s desk for years. The composer claimed that the work, as well as its A-minor companion that we hear tonight—eventually published as a pair in 1873—were preceded by 20 other attempts, as well as a private performance of the drafts of these two works by Joseph Joachim and his colleagues four years before they were allowed to reach the public. Despite misgivings, however, Brahms had created richly assured works, particularly the A-minor. It is more outward-looking than its counterpart, less dogged by the composer’s apprehensions. And within a program of experimental works, it reveals something of the mutability of Brahms’s music that Schoenberg would later term “progressive.”

The opening movement is a tribute to Joachim, its first subject centered on the violinist’s motto of F–A–E—“frei aber einsam” (free but lonely). Solitude may not be apparent within the four-part texture, though a parallel sense of melancholy is. And for all the violins’ duetting, there is a tug of war within the rhythmic profile of the accompaniment. More self-possessed music will follow, though nervousness remains. The songful Andante likewise features an ungainly accompaniment, though it is not without seraphic sweetness and, at times, Schubertian poise. Certainly, Brahms’s Viennese predecessor seems to provide the model for the anxious middle section, before a “false” reprise of the main theme in F major, and, finally, a return to the tonic major.

The short flick that starts the Quasi minuetto is also rooted in Schubert, namely the equivalent movement in his “Rosamunde” Quartet D 804, though Brahms offers a spryer, more scherzo-like trio. From this middle section he also derives the material for the movement’s close, suggesting another, much freer form. It is all part of a work in which things are not entirely what they seem, as confirmed by the finale, with its fluctuating rhythms. There are feints toward a csárdás and more austere counterpoint, as well as a gentle waltz. But Brahms ultimately persists with conflict, driving towards a determined minor-key cadence.

Gavin Plumley is a cultural historian who writes, broadcasts, and lectures widely on the art and music of Central Europe. He appears frequently on the BBC and contributes to newspapers, magazines, and opera and concert programs worldwide. His first book, A Home for All Seasons, was published last year.

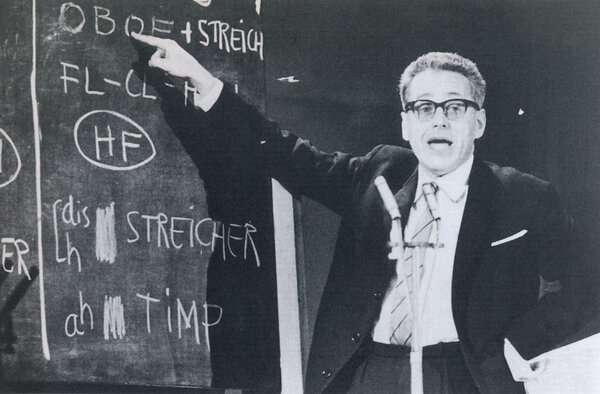

György Ligeti in the 1960s

Bereitschaft zum Abenteuer

„‚Hören‘ heißt: entdecken durch wahrnehmendes Beobachten“, sagt Helmut Lachenmann. Es geht nicht darum zu „verstehen“: „Was man mitbringen sollte, wenn man meine Musik wirklich hören will, ist eine gewisse Offenheit und Neugier. Ich brauche auch keine besondere Intelligenz, um einen Sonnenaufgang oder eine Bergbesteigung intensiv zu erleben. Ich sollte aber immerhin eine gewisse sensible Abenteuerbereitschaft mitbringen.“ Was Lachenmann hier formuliert, gilt ebenso für die vielgestaltige nächtliche Welt des Streichquartetts von György Ligeti und die kunstvolle Komplexität von Johannes Brahms’ Zweitem Streichquartett.

Essay von Antje Reineke

Bereitschaft zum Abenteuer

Streichquartette von Ligeti, Lachenmann und Brahms

Antje Reineke

„‚Hören‘ heißt: entdecken durch wahrnehmendes Beobachten“, sagt Helmut Lachenmann. Es gehe nicht darum zu „verstehen“: „Was man mitbringen sollte, wenn man meine Musik wirklich hören will, ist eine gewisse Offenheit und Neugier. Ich brauche auch keine besondere Intelligenz, um einen Sonnenaufgang oder eine Bergbesteigung intensiv zu erleben. Ich sollte aber immerhin eine gewisse sensible Abenteuerbereitschaft mitbringen.“ Was Lachenmann hier für die Begegnung mit seinen eigenen faszinierenden Klangwelten formuliert, gilt ebenso für die Annäherung an die vielgestaltige nächtliche Welt des Streichquartetts von György Ligeti, der im vergangenen Mai hundert Jahre alt geworden wäre, und die kunstvolle Komplexität von Johannes Brahms’ Zweitem Streichquartett.

Ligetis Erstes Streichquartett mit dem Titel Métamorphoses nocturnes ist ein relativ frühes, stilistisch für ihn untypisches Stück. Er komponierte es 1953/54 in Ungarn, das kulturell im Zeichen des „sozialistischen Realismus“ stand. Selbst von den Werken des großen „Nationalkomponisten“ Béla Bartók wurden nur wenige aufgeführt, und seine von Ligeti besonders geschätzten mittleren Streichquartette zählten nicht dazu. Da Kontakte ins Ausland unmöglich waren, habe er an neuerer Musik außer Bartók nur etwas Strawinsky und Berg gekannt, erinnerte sich der Komponist. Die für die ungarischen Machthaber inakzeptable Modernität seines Ersten Quartetts und die „Bindung an das Ethos der kompositorischen Haltung Haydns und Beethovens“ empfand Ligeti als „doppelte Panzerung gegen die erniedrigende Kunstdiktatur“. An eine Aufführung war damals in Ungarn natürlich nicht zu denken. Das Quartett erklang erstmals 1958 in Wien, nachdem Ligeti 1956 im Anschluss an den niedergeschlagenen Volksaufstand in den Westen geflohen waren.

Die Partitur besteht aus einem einzigen, mehrfach untergliederten Satz. „Metamorphosen bedeutet hier eine Folge von Charaktervariationen ohne ein eigentliches Thema, doch entwickelt aus einem motivischen Grundkeim“, erklärt Ligeti. „Neben Bartók waren für mich Beethovens Diabelli-Variationen das ‚heimliche Ideal‘.“ Dieser „Keim“, ein einfaches viertöniges Motiv, wird von der ersten Violine vorgestellt und sogleich erweitert. In dem wechselvollen Aufbau aus schnellen und langsamen, scherzohaften, und tänzerischen Abschnitten sowie einem rondoartigen Schlussteil schimmert die traditionelle Satzfolge durch, ohne dass sich das Werk schlüssig als Sonatenzyklus interpretieren ließe. Am Ende kehrt das Quartett zu seinem Anfang zurück, wobei die Violinen von Viola und Cello „ironisch nachgeahmt“ werden (so die Vortragsanweisung). Das „schillernde, statische Klanggewebe“ aus Flageolett-Glissandi, das diese Reprise umgibt, sowie der vorangehende rasend schnelle, „sehr gleichmäßig, wie ein Präzisionsmechanismus“ zu spielende Abschnitt weisen bereits, so Ligeti selbst, auf Elemente seines späteren Stils voraus.

Das poetische Attribut „nächtlich“, das im Übrigen auf Bartók verweist, beschreibt die von scharfen Kontrasten geprägte Stimmung: sanft, ausdrucksvoll, sehr launenhaft, kräftig, wild, heiter, ekstatisch und klagend – so lauten einige der Vortragsanweisungen, die sich allein auf den ersten Seiten der Partitur finden. Vieles scheint seltsam verfremdet, die Tempi, dynamischen Kontraste und Akzente sind mitunter extrem. Selbst das scheinbar friedliche Andante tranquillo in der Mitte des Stücks steigert sich beängstigend. Die ungemein farbige Klangwelt der Partitur macht reichlich Gebrauch von Techniken und Elementen wie dem weichen Klang von am Griffbrett und dem schärferen von am Steg gespielten Tönen, von Pizzicati, Flageolett, Glissandi, Trillern und Tremoli. Im Ganzen scheinen die unheimlichen, bedrohlichen Seiten der Nacht zu überwiegen. Ligeti hat sich dazu nicht näher geäußert, doch erklärte er in anderem Zusammenhang ganz allgemein, seine Musik sei nie Programmmusik, „aber sehr stark assoziationsgeladen“.

Den Klang neu beleuchten

In den späten 1960er Jahren entwickelte Helmut Lachenmann das Konzept einer „musique concrète instrumentale“. Damit stellte er den Klang ins Zentrum seines Komponierens, und zwar „Klang als charakteristische[s] Resultat und Signal seiner mechanischen Entstehung und der […] aufgewendeten Energie“ oder, wie er an anderer Stelle formulierte: die „konkrete Energie bei der Klanghervorbringung […], wobei ich aus dem Streichquartett einen sechzehnsaitigen Spielkörper machte, der – klingend, rauschend, behaucht, gepresst – mit seiner Körperlichkeit auf Traktierungen reagierte, in denen das traditionelle Spiel nur eine spezifische Variante des Umgangs mit dem Apparat darstellte“. Die Verfremdung der Klänge sollte dabei ihre „Hervorbringung ins Licht“ rücken. „Es geht ja nicht um irgendwie neue, schockierende Klänge“, betont Lachenmann, „sondern um immer wieder neu zu schaffende Zusammenhänge, die welchen Klang auch immer neu beleuchten.“

Zu diesem Zweck erfand der Komponist zahlreiche Spieltechniken. Vielfach etwa arbeitet er mit Varianten des Bogendrucks: Beim Streichen ohne Druck (flautando) kann das Geräusch des Reibens vom Bogenhaar auf der Saite hervortreten, während die Töne selbst „verschleiert“ bleiben und „eher als Schatten von Geräuschen (oder umgekehrt Geräusche bzw. tonloses Rauschen als Schatten von intervallisch präzise kontrollierten Tönen und Sequenzen)“ fungieren. Oft kommt eine Verlagerung des Bogens zwischen Grifffinger und Steg hinzu, die „ein Hell-dunkel-Glissando des Streichgeräusches“ bewirkt. Ein hoher Druck erzeugt ein „Rattern“, das mit einem Glissando kombiniert sein kann; durch ein tonloses Streichen auf Steg, Holzdämpfer oder Schnecke entsteht ein Rauschen.

Lachenmanns Drittes Streichquartett Grido, uraufgeführt 2001 in Melbourne durch das Arditti Quartet und im folgenden Jahr revidiert, verwendet neben den neuen Klängen wieder vermehrt traditionelle Spieltechniken und Elemente. Er habe „Vertrautes per reflektierten Kontext in ungewohntes Licht“ rücken wollen, sagt Lachenmann.

Dabei ergänzen sich „alte“ und „neue“ Klänge ganz natürlich, etwa in der Kombination von Flautando, Flageolett und „normal“ gestrichenen Liegetönen der Anfangspassage. Im Zusammenspiel der Techniken entstehen Kontraste, Steigerungen, Rücknahmen oder Echoeffekte. Hie und da blitzt das Fragment einer Melodie auf, baut sich plötzlich sogar ein C-Dur-Akkord auf, setzt Lachenmann den gleichmäßigen dreiteiligen Rhythmus einer Gigue ein, klingt ein Walzer an… Der Komponist spricht von „entleerte[n] Formeln“, deren „Präsenz als Ruinen so aktuell ist wie jedes mehr oder weniger faszinierende oder provozierende Geräusch“.

Der Titel des Quartetts ist aus den Namen der Mitglieder des Arditti Quartets gebildet: G[raeme Jennings], R[ohan de Saram], I[rvine Arditti], Do[v Scheindlin]. Gleichzeitig bedeutet „grido“ im Italienischen „Schrei“. Irvine Arditti hatte sich ein Stück gewünscht, das „lauter“ als Lachenmanns vorhergehende Quartette sein sollte. Da sich dessen Musik grundsätzlich durch eine oft stark zurückgenommene Dynamik auszeichnet, ist dies allerdings relativ zu sehen – wirklich laut geht es auch in Grido nur vorübergehend zu. Was mit „Schrei“ gemeint sein könnte und ob er einer negativen Emotion wie Schmerz und Wut oder einer positiven wie Freude und Übermut entspringt, bleibt insofern der Assoziation des Publikums überlassen.

Fest im Sattel

Johannes Brahms’ Freund und Biograph Max Kalbeck bezeichnete die Kammermusik des Komponisten als dessen „Leibpferd“, und dieses Bild hat sich erhalten. Wiewohl vereinfacht – in seiner Zeit diente es dazu, Brahms gegen die „Neudeutschen“ um Liszt und Wagner zu positionieren – ist es durchaus treffend. Sowohl als Komponist wie als Pianist beschäftigte er sich sein Leben lang mit Kammermusik. Das Streichquartett allerdings, so Kalbeck weiter, „warf den Reiter immer wieder ab“. Die Manuskripte zu mehr als 20 Quartetten soll Brahms vernichtet haben, bevor er im Sommer 1873 die beiden Werke op. 51 fertigstellte. Er war allgemein äußerst selbstkritisch – auch Werke anderer Gattungen verwarf er rigoros – und gerade das Streichquartett mit seinem homogenen vierstimmigen Satz galt seit dem späten 18. Jahrhundert als anspruchsvollste Gattung der Kammermusik.

Anders als die „Neudeutschen“ suchte Brahms nicht nach neuen Formen, sondern hielt an der klassischen viersätzigen Anlage fest, um sie von innen heraus zu verändern. Äußerlich überrascht am a-moll-Quartett einzig die Bezeichnung „Quasi Minuetto“, die auf die Zeit vor Beethoven zurückverweist, allerdings in Mendelssohns D-Dur-Quartett einen Vorläufer hat. Tatsächlich trägt der Satz, speziell im Allegretto vivace mit seinen flüchtigen Staccato-Ketten, auch Züge eines Scherzos. Ungewöhnlich ist außerdem der Umstand, dass dieses Allegretto durch eine nur fünftaktige Variante des Menuetts unterbrochen wird, die später auch dessen Reprise einleitet. Der Mittelabschnitt des Andante moderato beginnt als dramatischer Kontrast zum gesanglichen Rahmenteil, geht dann jedoch zu einem lyrischen Ton über und bezieht sich dabei deutlich auf das Kopfmotiv des Satzes. Im tänzerischen Schlussrondo kehrt wiederum nicht nur der Refrain, sondern auch das üblicherweise wechselnde Couplet zurück. Gegen Ende erscheint der Refrain völlig verwandelt: ruhig, leise, in Dur statt in Moll und zuletzt, in einem geradezu entrückten Moment, verbreitert – schlägt dann aber in einen rasanten Moll-Abschluss um. Der erste Satz dagegen ist ein klar gegliederter, eher lyrischer Sonatensatz. Sein weitgespanntes viertöniges Kopfmotiv fungiert als Motto, das die wichtigen Zäsuren markiert. Es enthält die Tonfolge F-A-E, die Brahms in der Vergangenheit im Sinne von „frei, aber einsam“ verwendet hatte.

Als charakteristisch für Brahms gilt die „Dichte“ des musikalischen Satzes, vor allem also die Vielzahl der motivischen Ableitungen, Varianten, weiträumigen Bezüge und kontrapunktischen Strukturen. Das Allegretto des dritten Satzes übernimmt zum Beispiel eine Staccato-Figur aus dem Menuett, die ihrerseits dessen Thema variiert. Anhand des zweiten Satzes hat Arnold Schönberg, der technisch an Brahms anknüpfte, gezeigt, wie sich ein ganzes Thema und damit letztlich weite Teile eines Satzes aus einem einzigen kurzen Motiv entwickeln lassen. Gut zu identifizierende Beispiele für Kontrapunktik bieten ein Fugato des Mottos am Ende des ersten Satzes und der Tranquillo-Abschnitt des Rondos, in dem erste Violine und Cello die Melodie im Kanon spielen.

So abstrakt all dies auf den ersten Blick klingen mag, bildet es doch die Basis für eine große Ausdrucksvielfalt. Es ist nicht entscheidend, jedes dieser Details hörend zu erkennen. Wichtig sind die von Lachenmann geforderte Offenheit und Neugier, um bei jeder Begegnung mit dem Quartett neue Details zu entdecken.

Antje Reineke studierte Historische Musikwissenschaft, Rechtswissenschaft und Neuere deutsche Literatur an der Universität Hamburg und promovierte dort mit einer Arbeit über Benjamin Brittens Liederzyklen. Sie lebt als freie Autorin und Lektorin in Hamburg.

The Artists

Quatuor Diotima

String Quartet

Quatuor Diotima

Founded by graduates of the Paris Conservatory in 1996, the Quatuor Diotima today is among the world’s leading string quartets, most notably due to its ongoing commitment to contemporary music. The four musicians have maintained close artistic relationships with many composers, including Helmut Lachenmann, Toshio Hosokawa, Miroslav Srnka, Albert Posadas, Gérard Pesson, Rebecca Saunders, and also Pierre Boulez, who revised his Livre pour quatuor for the Quatuor Diotima. The ensemble released a recording of the work’s definitive version in 2015. The quartet’s large discography includes many award-winning CDs, among them a complete recording of works for string quartet by the composers of the Second Viennese School, Béla Bartók’s complete string quartets, and portrait albums dedicated to the music of Gérard Pesson, Enno Poppe, Stefano Gervasoni, Thomas Simaku, and most recently György Ligeti. During the 2022–23 season, the Quatuor Diotima premiered new works by Bruno Mantovani, Mauro Lanza, Sasha J. Blondeau, Lisa Streich, Olga Neuwirth, and Misato Mochizuki. The four musicians regularly lead masterclasses and workshops, passing on their experience to the next generation of artists.

October 2023