Tabea Zimmermann Viola

Lise Guérin, Brian Isaacs, Eric Seohyun Moon Viola

Students in Tabea Zimmermann's class at the Frankfurt University of Music and Performing Arts

Program

Max Reger

Suite for Solo Viola in G minor Op. 131d No. 1

Johann Sebastian Bach

Partita for Solo Violin No. 2 in D minor BWV 1004

Arrangement for Solo Viola

Georges Lentz

Anyente for Solo Viola

Franz Anton Hoffmeister

Etude for Solo Viola No. 1 in C major

Enno Poppe

Filz

Version for Solo Viola

Garth Knox

Marin Marais Variations on Folies d’Espagne

for four Violas

Max Reger (1873–1916)

Suite for Solo Viola in G minor Op. 131d No. 1 (1915)

I. Molto sostenuto

II. Vivace – Andantino

III. Andante sostenuto

IV. Molto vivace

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Partita for Solo Violin No. 2 in D minor BWV 1004 (1720)

Arrangement for Solo Viola

I. Allemande

II. Corrente

III. Sarabada

IV. Giga

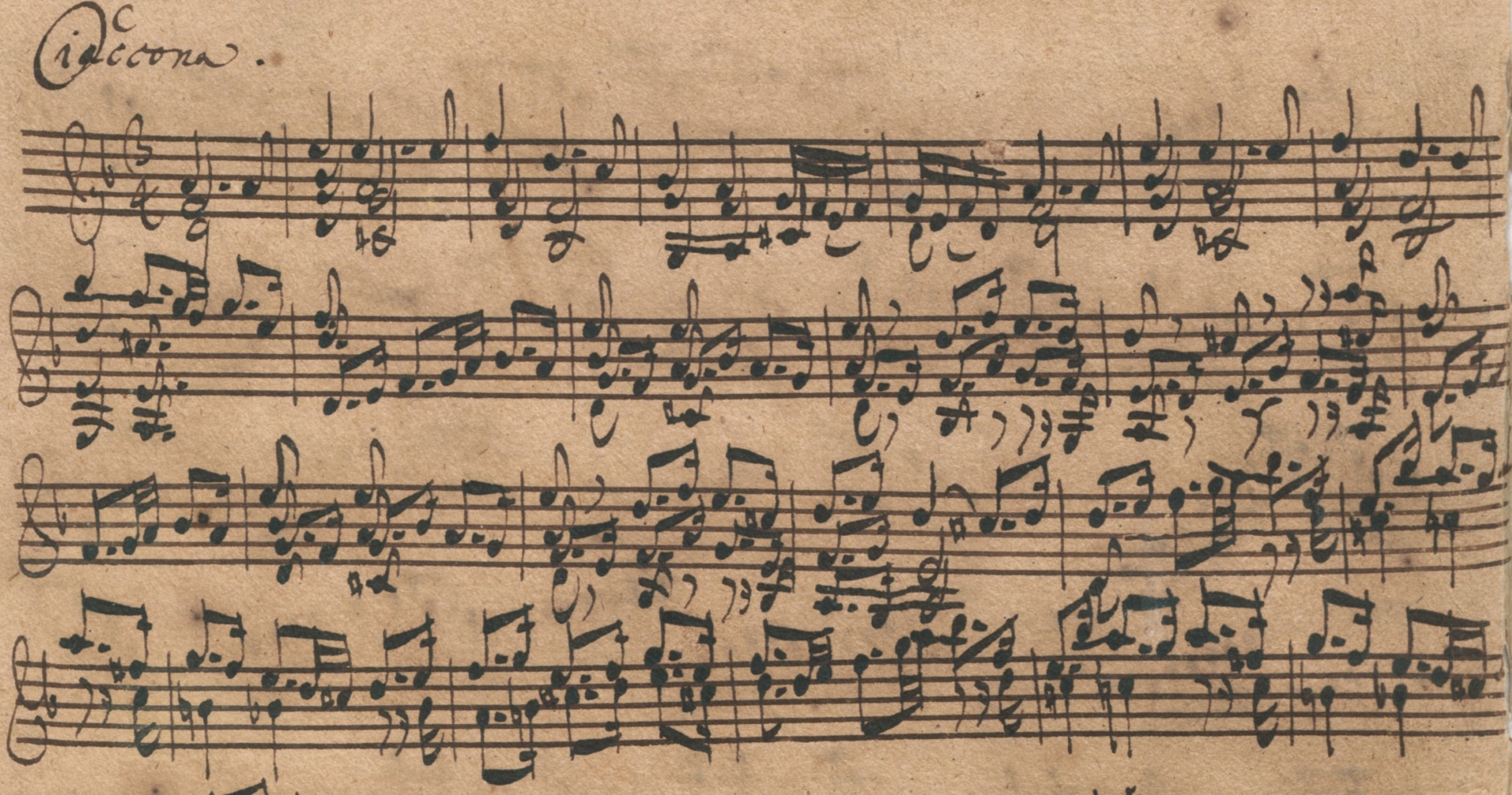

V. Ciaccona

Georges Lentz (*1965)

Anyente for Solo Viola (2019–24)

from Mysterium („Caeli enarrant ...“ VII)

Intermission

Franz Anton Hoffmeister (1754–1812)

Etude for Solo Viola No. 1 in C major (1802–3)

Allegro

Enno Poppe (*1969)

Filz

Version for Solo Viola (2013–4/2017)

Garth Knox (*1956)

Marin Marais Variations on Folies d’Espagne for four Violas (2007/10)

Thème. Lento – Variations I–VIII

Max Beckmann, The Composer Max Reger (1917)

Virtuosic and Melancholic

The viola is the Cinderella of the string family. Long regarded as a musical helpmate, subservient to the violin and cello, it came into its own as a solo instrument in the early 20th century, around the time Max Reger wrote the unaccompanied Suite that opens Tabea Zimmermann’s recital.

Essay by Harry Haskell

Virtuosic and Melancholic

Music for Solo Viola

Harry Haskell

The viola is the Cinderella of the string family. Long regarded as a musical helpmate, subservient to the violin and cello, it came into its own as a solo instrument in the early 20th century, around the time Max Reger wrote the unaccompanied Suite that opens tonight’s program. Tabea Zimmermann is one of a cadre of contemporary virtuosos who have enriched the instrument’s repertory in recent years. Her repertoire ranges from transcriptions of Baroque works, such as Bach’s D-minor Partita for Solo Violin, to music made to order for her by contemporary composers like Enno Poppe and Georges Lentz. “I think what’s so wonderful about the viola is its versatility,” Zimmermann says. “The viola can be both virtuosic and melancholic. It is indeed a niche instrument. But I’ve come to terms with the fact that I can perform in a certain niche. And I try to use this position to introduce listeners to the beauties of our repertory.”

In the Spirit of Bach

Like Ferruccio Busoni, Max Reger was strongly influenced by the 19th-century Bach revival and emulated the Baroque master’s contrapuntal prowess. Unlike his Italian friend, however, Reger was drawn to Bach’s chorale preludes less as autonomous works of art than as embryonic “symphonic poems” that mysteriously adumbrated Wagner’s music dramas. Reger was hardly alone in locating the sources of Wagner’s “grand style” in Bach’s music, but his organ sonatas, fantasias, and other works, with their densely woven contrapuntal textures, relate more fundamentally to his own compositional priorities in fashioning a polyphonic style of equal depth and rigor for the modern era. This tendency is particularly pronounced in a cluster of chamber works that Reger wrote a year or so before his death, at age 53, in 1916. In addition to three Suites for Solo Viola, these works—variously inspired by Baroque forms and procedures—include six Preludes and Fugues for Solo Violin, three Suites for Solo Cello, and three canons and fugues “in ancient style” for violin duo.

In place of the stylized dances that comprised the instrumental suites of Bach and his contemporaries, Reger lays out his G-minor Suite in four “abstract” movements identified only by their tempo markings. All are in ternary (ABA) form, their sturdy symmetry mirroring the periodic phrase structure of the melodies. Texturally, too, Reger’s music is notable for its clarity and simplicity, combining single-line melodic passages with chains of double-stops and occasional broken chords. Despite its highly chromatic sound world, the G-minor Suite is unmistakably infused with Bach’s spirit. As Zimmermann puts it, Reger “executed the Baroque form in a very Romantic way.”

One Instrument, Many Voices

Bach was in his early 30s and already enjoyed considerable renown as an organ virtuoso when he accepted an appointment as director of music to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen in 1717. The young composer counted himself lucky to be in the employ of a “a gracious Prince who both loved and knew music.” It was during his six happy years in Cöthen that Bach wrote much of his most beloved instrumental music, including the six “Brandenburg” Concertos and the six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin BWV 1001–6. The autograph score of the latter is dated 1720, but some of the music was probably composed during Bach’s previous appointment as court organist in Weimar. It has been suggested that the violin solos were written for a member of the small but excellent court orchestra at Cöthen.

A number of German and Italian composers had written music for solo violin in the 17th century, but never on the scale that Bach attempted. Nor had anyone achieved such breathtaking contrapuntal and harmonic complexity with a single melodic instrument. As Johann Nikolaus Forkel observed in 1802, Bach “has so combined in a single part all the notes required to make the modulations complete that a second part is neither necessary nor desirable.” The Partita in D minor starts out as a conventional four-dance suite, with a plangent, dark-hued Allemanda, a somewhat lighter-spirited Corrente, a grave and intense Sarabanda, and an agile, high-stepping Giga. All begin with the same sequence of chords, whose slow-moving base line (D–C sharp–D–B flat–A) serves as a kind of a unifying “head-motive.” This recurring bass pattern is easiest to hear in the concluding Ciaconna, a highly elaborate version of a popular dance imported from Latin America by way of Spain and originally performed by voice and guitar. Often played on its own, the Chaconne is one of Bach’s noblest and most celebrated creations. Its monumental architecture rests on a simple but sturdy foundation: the ever-changing ostinato bass provides the harmonic underpinning for a series of 32 stunningly imaginative variations, ranging in length from four to 12 bars.

Celestial Music

“The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork”: Bach set this text, from Psalm 19, in the opening chorus of his 1723 cantata Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes. Some 270 years later, Australian composer Georges Lentz adopted the corresponding Latin rubric, Caeli enarrant…, as the title of an open-ended cycle of works reflecting his interests in astronomy, Gregorian chant, and Aboriginal art, as well as his ongoing interrogation of his Catholic faith. Lentz describes Mysterium—the seventh part of the cycle—as “a conceptual work in an open form, consisting of numerous blocks that can be put together ad libitum.” Inspired by the inaudible celestial harmonies that the ancient Greeks called the “Music of the Spheres,” Lentz sought to “write music which does not evolve or unfold, but simply ‘is.’ … ‘Mysterium’ is mostly soft, and tension results mainly from the polarity between sound and silence, tonal and quarter-tone elements, homophonic lines and complex polyphonic material, a regular crotchet [quarter-note] beat and graphically notated rhythmic unpredictability, expanded and contracted time.” The soundscape of Anyente (an Indigenous word for “one”), which Zimmermann premiered in 2021, also owes much to what Lentz calls “the extreme loneliness, the great silence and a sense of existential fragility found in the Australian Outback.”

Franz Anton Hoffmeister had more mundane motives for composing his 12 Etudes for Solo Viola in 1803. One of Vienna’s leading music publishers, he wrote a prodigious quantity of chamber music, operas, symphonies, and concertos that not only generated income for the firm but helped establish his bona fides with clients like Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. (Mozart’s “Hoffmeister” String Quartet of 1786 is a testament to their friendship.) The Etude in C major is both an aesthetically satisfying piece of concert music and a practical compendium of virtuoso string techniques—sparkling spiccato passagework, chains of double-stops, and so on—written at a time when composers like Mozart were just beginning to explore the viola’s solo potential.

“Dented Nature”

Enno Poppe’s Filz (Felt) is the solo version of a chamber concerto for viola, four bass clarinets, and strings that Tabea Zimmermann premiered in 2015. The longtime director of the Berlin-based new-music ensemble Mosaik, Poppe views the compositional process as a laboratory experiment whose outcomes are never fully predictable, however rationally designed the experiment may be. Poppe’s scientific mindset is manifest in his interest in fractals and mathematical models of plant growth. Filz explores the organic potential of a basic idea—a wavelike oscillating figure that, in the original concerto, is presented by the violist and then refracted as it passes through the sonic prism of the orchestra. In reconceiving the work for solo viola, Poppe reveals an affinity with “spectralist” composers, for whom sound and timbre are independent physical properties that can be manipulated and transformed. He applies this principle to every parameter of the music, from melody and harmony (he once suggested that “one could describe my chords as distorted spectral chords, or as dented nature”) to the carefully calibrated vibratos and glissandos that figure prominently in his musical language. Poppe’s interest in “the physicality of the musicians”—the way they move in performance--is reflected in the music’s gestural component. “I write with my own body,” he says. “I’ve sung all the parts. Every note has been in my mouth, so to speak—I’ve played it or executed it in some way. I can be quite noisy sometimes when composing, because everything goes right through me.”

Like Poppe, Irish composer Garth Knox has benefited from his association with the Ensemble intercontemporain and the Arditti Quartet, both adventurous incubators of avant-garde music. A distinguished violist himself, Knox has long been active in expanding his instrument’s repertoire and technical vocabulary. The viola quartet Marin Marais Variations on Folies d’Espagne, from a pedagogical collection entitled Viola Spaces, takes its cue from a set of virtuosic variations by the legendary French viola da gamba player Marin Marais. Knox’s involvement with the Baroque period is more than purely historical: he has recently taken up the viola d’amore—a member of the viol family featuring a second set of strings that vibrate sympathetically with the main strings—with an eye to making it part of the modern instrumentarium. Each of his own variations on the well-known “Folies d’Espagne” theme focuses on a different aspect of string technique—many of them completely unknown to Marais.

A former performing arts editor for Yale University Press, Harry Haskell is a program annotator for Carnegie Hall in New York, the Brighton Festival in England, and other venues, and the author of several books, including The Early Music Revival: A History, winner of the 2014 Prix des Muses awarded by the Fondation Singer-Polignac.

The Chaconne from the D-minor Partita BWV 1004 in Bach’s manuscript (Staatsbibliothek Berlin)

„Das Bratschespielen neu lernen“

In ihrem Soloabend präsentiert Tabea Zimmermann Werke aus jüngster Zeit, aber auch Musik von Max Reger, dem Beethoven-Zeitgenossen Franz Anton Hoffmeister und die Bearbeitung eines Violinklassikers von Bach.

Essay von Jürgen Ostmann

„Das Bratschespielen neu lernen“

Zum Soloabend mit Tabea Zimmermann

Jürgen Ostmann

Im Lauf seines Lebens sah sich Max Reger immer wieder dem Vorwurf ausgesetzt, seine Musik sei von massiger Klanglichkeit, überbordender Polyphonie und ausschweifender harmonischer Komplexität bestimmt. Er selbst war sich dieser Tatsache wohl bewusst, wie eine Tagebucheintragung seines Vertrauten Fritz Stein aus dem Jahr 1914 beweist: „Mittwoch. 1. April. Auf dem Heimweg spricht er über Komposition für Violinsolo, die ihn außerordentlich reize. […] ‚Das Komponieren für Solovioline ist für mich eine Art musikalischer Keuschheitsgürtel.‘ […] R. will als op. 131 eine Reihe von Prael. u. Fugen für Viol. allein komponieren, jedes Jahr ein paar.“ Viele Jahre blieben Reger nicht mehr: 1916 starb er im Alter von nur 43 Jahren an Herzversagen. In sein vollendetes Opus 131 nahm er schließlich auch eine Reihe von Kompositionen auf, die über die von Stein genannten Parameter hinausgehen: Neben den Sechs Präludien und Fugen für Violine solo (op. 131a) sind darin „Drei Duos (Kanons und Fugen) im alten Stil“ für zwei Violinen (op. 131b), die Drei Suiten für Violoncello solo (op. 131c) und schließlich die Drei Suiten für Viola solo (op. 131d) versammelt.

Die Bratschensuite g-moll beginnt mit einem Molto sostenuto, das die Fähigkeit des Instruments zu dunklem, leidenschaftlichem Ausdruck herausstellt. Kapriziös gibt sich das folgende Vivace mit Staccato-Artikulation und zahlreichen Sprüngen zwischen entfernten Saiten; die schnellen Außenabschnitte umschließen einen ausdrucksvollen Mittelteil. In parallelen Terzen und Sexten bewegt sich das Andante sostenuto, das ebenso knappe wie rasante Finale ist dagegen durchgehend einstimmig gehalten. Seine gleichförmige Sechzehntelbewegung wird durch zahlreiche dynamische Wechsel belebt.

Gipfelpunkt des Streicherrepertoires

Im Solorepertoire für Streichinstrumente nehmen die beiden großen Werkzyklen Johann Sebastian Bachs eine besondere Stellung ein. Von seinen Sechs Sonaten und Partiten für Violine hat sich ein kalligraphisch besonders wertvolles Autograph erhalten. Es trägt die Jahreszahl 1720 – was allerdings keineswegs ausschließt, dass Bach diese Stücke bereits früher komponiert oder zumindest begonnen haben könnte. In jedem Fall ist über einen konkreten Anlass ebenso wenig bekannt wie über einen möglichen Auftraggeber oder Widmungsträger (die sorgfältige Handschrift scheint immerhin auf eine besondere Bestimmung der Werke hinzudeuten). Den Begriff „Partia“ (oder Partita) verwendet Bach hier synonym mit der Bezeichnung Suite – gemeint ist eine Reihe von Tanzsätzen, die oft durch ein Präludium eingeleitet werden. Im Unterschied zu anderen Werken Bachs enthält die Partita Nr. 2 d-moll – die Tabea Zimmermann in einer Bearbeitung für Viola interpretiert – zwar kein derartiges Vorspiel, dafür aber alle vier Standardsätze der Suite: die mäßig schnelle, geradtaktige Allemande, die lebhafte Courante im Dreiermetrum, die langsame, feierliche Sarabande und die schnelle, bewegte Gigue. Anders als sonst üblich folgt darauf allerdings noch ein weiterer Satz – die Chaconne oder „Ciaccona“, das berühmteste Stück der ganzen Serie und ein Gipfelpunkt der Violinmusik. Als Chaconne bezeichnet man laut Johann Gottfried Walthers Musicalischem Lexicon von 1732 einen „Tanz, und eine Instrumentalpièce, deren Baß-Subjectum oder thema gemeiniglich aus vier Tacten in 3/4 bestehet, und, so lange als die darüber gesetzte Variationes oder Couplets währen, immer obligat, d.i. unverändert bleibet.“ Bachs Chaconne geht insofern über das traditionelle Muster hinaus, als sich ihr harmonisches Schema im Verlauf der 64 Variationen verändert. Durch den Wechsel von d-moll über D-Dur zurück nach d-moll gliedert sich das Stück in drei Teile, die jeweils in sich eine eindrucksvolle Steigerungsdramaturgie aufweisen.

Den Faden fortspinnen

Georges Lentz, in Luxemburg geboren und seit 1990 in Australien lebend, schreibt zu seiner Komposition Anyente: „Mein neues Solobratschenstück für Tabea Zimmermann, ursprünglich für die Bonner Beethovenwoche 2020 konzipiert, handelt vordergründig von der Taubheit und Einsamkeit des späten Beethoven. Nachdem die zeitgenössische Komponente jenes Festivals coronabedingt ausfiel, blieb das Werk eine Zeit lang liegen. Erst bei Reisen ins australische Outback 2021 hatte ich die Skizzen wieder im Gepäck, und ich wurde erneut von der Stille und tiefen Nacht in der Wüste überwältigt, sodass das Werk, nun unter dem Titel Anyente, über Beethovens Isolation hinaus, ganz allgemein zu einer kleinen Meditation über unsere existentielle Zerbrechlichkeit, Einsamkeit und das Auf-uns-selbst-Zurückgeworfensein wurde (‚anyente‘ ist ein Wort aus einer der Sprachen des Arrernte-Volkes Zentralaustraliens und bedeutet soviel wie ‚eins‘ oder ‚allein‘, also solo). Das Werk enthält einige versteckte Anspielungen an späte Beethoven-Quartette (der Komponist spielte übrigens in jungen Jahren selbst Bratsche im Quartett). Rhythmisch war das Stück für mich auch eine Skizze für mein zur selben Zeit entstehendes Violinkonzert […] und geriet gleichzeitig zu einer Art Miniatur-Spiegelbild meines digitalen Werks String Quartet(s) in der Cobar Sound Chapel. Diese wenn auch versteckten Bezüge zwischen Werken sind mir immer wichtig bei der Arbeit. Anyente spinnt jedoch vor allem mein Werk Monh für Bratsche und Orchester (ebenfalls für Tabea Zimmermann geschrieben) weiter. Es greift den Faden genau dort auf, wo Monh verklang. Ein glitzernder Sternenhimmel wird immer wieder von stiller Schwärze durchlöchert, kehrt sich in obsessiver Wiederholung in sein aufbegehrendes Gegenteil, dem Punkthaften wird eine lange Linie entgegengestellt. Das Werk ringt um einen Bezug, gar eine Aussöhnung zwischen diesen sich oft schroff gegenüberstehenden Charakteren. Nachdem Tabea Zimmermann Anyente 2021 in einer frühen Fassung in der Philharmonie Luxemburg vorgestellt hatte, arbeitete ich weiter daran, fügte dem ‚Bau‘ einen Flügel hinzu und versuchte, den finalen Absturz in die Tiefe und schließlich ins Nichts (‚a niente‘) stringenter einzubinden. Dies ist die Erstaufführung der neuen, endgültigen Fassung.“

„…mein geliebter Herr Bruder in der Tonkunst“

Der Name Franz Anton Hoffmeisters ist heute vor allem noch durch seine Aktivitäten als Verleger bekannt, obgleich er sich in diesem Geschäftsfeld nur zeitweise betätigte. Ein 1784 in Wien gegründetes Unternehmen verkaufte er 1795 zum größten Teil an einen Konkurrenten, und am „Bureau de Musique“, das er 1800 in Leipzig mit aufgebaut hatte, war er nur wenige Jahre beteiligt (es ging später an den bis heute bestehenden Verlag C.F. Peters über). Doch neben seinen eigenen Stücken hatte Hoffmeister auch viele Werke berühmter Komponisten im Programm – etwa von Haydn, den er in einem Brief einmal einen „geizigen Charakter“ nannte. Ihm selbst hätte man diesen Wesenszug kaum nachsagen können – Mozart etwa erhielt von Hoffmeister großzügige Vorschüsse, beispielsweise auf das Klavierquartett KV 478. Auch Mozarts Streichquartett KV 499 erschien erstmals bei Hoffmeister, ebenso wie die „Pathétique“-Sonate von Beethoven, der den Verleger in Briefen mit „mein geliebter Herr Bruder in der Tonkunst“ ansprach. 1806 veräußerte Hoffmeister auch die Reste seines Wiener Verlags, um sich noch intensiver als zuvor dem Komponieren zu widmen. Sein Schaffen auf diesem Gebiet umfasst nicht weniger als neun Singspiele, fast 70 Symphonien, viele Serenaden, Solokonzerte und Kammermusikwerke in gebräuchlichen, aber auch ausgefalleneren Besetzungen. Für die Bratsche schrieb Hoffmeister neben einem Solokonzert 12 Etüden, die gut auf die spieltechnischen Anforderungen des klassischen Viola-Repertoires vorbereiten. Die Nr. 1 in C-Dur bietet Herausforderungen in Bariolage (dem schneller Wechsel zwischen einer gleichbleibenden und einer sich verändernden Note auf benachbarten Saiten), Spiccato (Springbogen), Doppelgriffen und Arpeggien über drei Saiten.

Neue Horizonte

Völlig andere Klangwirkungen bietet Enno Poppes Bratschenkonzert Filz – dazu zählen insbesondere Dritteltöne, Glissandi und spezielle Arten des Vibratos. Inspiriert durch Poppes Erfahrung mit traditioneller koreanischer Musik, entstand das Werk für Tabea Zimmermann, die in einem Interview erklärte, sie habe dafür „das Bratschespielen neu lernen“ müssen. Warum? „Weil mir kein anderes Werk für Bratsche einfällt, in dem das Thema Glissando so eingehend behandelt und abgehandelt wird wie hier. Mein absolutes Gehör (oft ein Segen, gelegentlich auch ein Fluch) hilft, mir die Töne vom Papier sehr schnell auch ‚absolut‘ vorstellen zu können. Den wandelbaren Prozess der Töne, wie ihn Poppe komponiert, muss ich mir aber neu erarbeiten, was sehr bereichernd ist. Ich bin ohnehin in einer Phase, in der mich der ‚Weg von‘ und der ‚Weg hin zu‘ sehr interessiert. Da kam das Werk von Poppe genau zur rechten Zeit, um das nun auch instrumental umzusetzen.“ Auf die 2013/14 komponierte Originalfassung, in der die Bratsche von einem Kammerorchester aus Streichern und vier Klarinetten begleitet wird, ließ Poppe 2017 noch eine Version für Soloviola folgen. Filz ist im Übrigen einer der für Poppe typischen Ein-Wort-Titel, die der Komponist nicht kommentiert, die aber im Bewusstsein der Hörenden weite Assoziationsräume öffnen. In diesem Fall könnte man an die Elastizität des aus zusammengestauchten Wollfasern bestehenden Materials denken, an seine wärmeisolierende Funktion oder die abdämpfende Wirkung, die ja auch beim Bau verschiedener Instrumente geschätzt wird.

Der aus Irland stammende Garth Knox war als Bratscher viele Jahre lang Mitglied des Ensemble intercontemporain und des Arditti Quartet, zweier Formationen, die sich der zeitgenössischen Musik verschrieben haben. Daneben beschäftigt er sich mit historischen Instrumenten wie der Viola d’amore oder der mittelalterlichen Fiedel. Bekannt wurde Knox aber auch als Komponist von Viola Spaces, einem zweibändigen Kompendium moderner Spieltechniken auf der Bratsche. Als dessen dritten Band legte er 2007 seine Variationen über die „Folies d’Espagne“ von Marin Marais vor. Deren Thema hatte der französische Gambist allerdings gar nicht selbst erfunden: Es handelt sich vielmehr um eine Basslinie mit bezifferten Harmonien, die vielen Musikern des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts als Improvisations- und Kompositionsgrundlage diente. Zu Beginn seines Stücks lässt Knox den Marais’schen Originalsatz von vier Bratschen intonieren. Die folgenden Variationen erkunden der Reihe nach verschiedene Spielweisen: von „sul tasto“ (Bogenführung über dem Griffbrett) über Flageoletttöne, Glissandi, Pizzicato und „col legno“ (mit der Holzseite des Bogens) bis hin zu wischenden und kreisenden Bogenbewegungen, Vierteltönen, „sul ponticello“ (Bogenführung am Steg) und Tremolo.

Jürgen Ostmann studierte Musikwissenschaft und Orchestermusik (Violoncello). Er lebt als freier Musikjournalist und Dramaturg in Köln und arbeitet für verschiedene Konzerthäuser, Rundfunkanstalten, Orchester, Plattenfirmen und Musikfestivals.

The Artists

Tabea Zimmermann

Viola

Tabea Zimmermann studied with Ulrich Koch at the Freiburg Musikhochschule and with Sándor Végh at Salzburg’s Mozarteum. She is widely regarded as one of today’s leading violists and performs with the world’s major orchestras, having served as artist in residence with the Berliner Philharmoniker, Bavarian Radio Symphony, and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra, among others. Collaborations with artists such as Javier Perianes, Jörg Widmann, and the Belcea Quartet form an important part of her chamber music activities. Until 2016, she performed with Antje Weithaas, Daniel Sepec, and Jean-Guihen Queyras in the Arcanto Quartet. Tabea Zimmermann has premiered a number of new works, including György Ligeti’s Sonata for Solo Viola, which is dedicated to her, Wolfgang Rihm’s Second Viola Concerto, Heinz Holliger’s Recicanto, and Enno Poppe’s Filz. In addition to her performing career, she serves as President of the Swiss Hindemith Foundation and, since 2023, has been Chair of the Board of Trustees of the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation, whose music prize she was awarded in 2020. Following 20 years on the faculty of the Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin, she returned to the Frankfurt Musikhochschule as a professor in 2023.

November 2024

Lise Guérin

Viola

A graduate of the Lübeck Musikhochschule in the class of Pauline Sachse, French violist Lise Guérin has been a student of Tabea Zimmermann in Frankfurt since September 2024. She has been a member of the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, the Zermatt Festival Academy, and the Seiji Ozawa Academy and is the founder of the Monte Rosa Ensemble, which regularly performs throughout Germany. As a chamber musician, she has appeared at Victoria Hall in London, Hamburg’s Laeiszhalle and Elbphilharmonie, and the Salzburg Festival and the Bolzano Festival, working with artists including Nobuko Imai, Hariolf Schlichtig, the Artemis Quartet, and the Jerusalem Quartet, among others. She recently recorded George Enescu’s Octet alongside Tabea Zimmermann.

Brian Isaacs

Viola

New York–born Brian Isaacs is a student in Tabea Zimmermann’s class at the Frankfurt Musikhochschule and a member of the Karajan Academy of the Berliner Philharmoniker, where he is mentored by Sebastian Krunnies. He previously received his Master of Music and a Bachelor’s degree in sociology from Yale University. He has won prizes at several international competitions, including most recently the Max Rostal Competition of the Berlin University of the Arts and the Oskar Nedbal International Viola Competition, and has attended master classes with Misha Amory, Yuri Bashmet, Nobuko Imai, and Antoine Tamestit. Performances have taken him to the Gstaad String Academy, La Jolla SummerFest, and the Verbier Festival Academy, among other venues.

Eric Seohyun Moon

Viola

Eric Seohyun Moon has won numerous national competitions in South Korea as well as the Concorso Gaetano Zinetti and was finalist at the 2019 Prague Spring competition. In addition to his studies with Tabea Zimmermann, he has taken part in the Verbier Festival Academy and attended master classes with Antoine Tamestit, Lawrence Power, Gábor Takács-Nagy, and Nils Mönkemeyer. From 2022 to 2024, he was a member of the Karajan Academy of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with whom he also performed as a guest musician at the festivals of Salzburg, Lucerne, and Baden-Baden. He has appeared as a soloist with the Korean National Symphony Orchestra, the Hradec Králové Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Bucheon Philharmonic Orchestra, among others.