Daniel Sepec Violin

Hille Perl Viol

Lee Santana Theorbo and Archlute

Michael Behringer Harpsichord and Organ

Program

Johann Heinrich Schmelzer

Sonata IV from Sonatae unarum fidium for Violin and Basso continuo

Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in A minor Op. 3 No. 1 La Stella

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in D major Op. 3 No. 4 La Castella

Sonata for Violina and Basso continuo in D major Op. 3 No. 2 La Melana

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in A minor Op. 3 No. 2 La Cesta

Vincenzo Bonizzi

Jouissance vous donneray

Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger

Toccata

Gagliarda

Corrente

from Libro primo d'intavolatura di lauto

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in F major

Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (1623–1680)

Sonata IV from Sonatae unarum fidium

for Violin and Basso continuo (1664)

I. [Chaconne]

II. Sarabande

III. Guige

IV. [without title]

V. Allegro – Presto

Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli (1624–c. 1687)

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in A minor Op. 3 No. 1 La Stella (1660)

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in D major Op. 3 No. 4 La Castella

Vincenzo Bonizzi (?–1630)

Jouissance vous donneray

from Alcune opere di diversi auttori, passagiate per la viola bastarda (1626)

Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli

Sonata for Violina and Basso continuo in D major Op. 3 No. 2 La Melana

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in A minor Op. 3 No. 2 La Cesta

Intermission

Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger (1580–1651)

Toccata

Gagliarda

Corrente

from Libro primo d'intavolatura di lauto (1611)

Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in E minor Op. 4 No. 1 La Bernabea

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in F major Op. 4 No. 3 La Monella Romanesca

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644–1704)

Sonata for Violin and Basso continuo in F major (1681)

I. Adagio – Presto

II. Aria – Variatio

III. Variatio. Grave

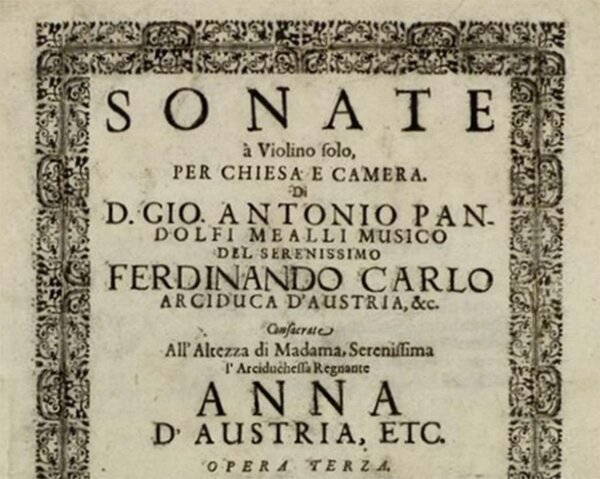

First edition of Pandolfi's Opus 3 Sonatas, Innsbruck 1660

Rediscovering a Composing Virtuoso

It took until the final quarter of the 20th century, in the wake of the intensive preoccupation with Early Music within the framework of historically informed performance practice, for the music-historical significance of Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli's works to become apparent. These sonatas form a link between the virtuoso Italian instrumental style of the Early Baroque and the violin music of the High Baroque in southern Germany and Austria, culminating in the music of composers such as Schmelzer and Biber.

Essay by Franz Gratl

Rediscovering a Composing Virtuoso

The Life and Works of Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli

Franz Gratl

The Portuguese word barocco was originally utilized to describe irregularly shaped pearls. It only became established during the 19th century as the term Baroque to encompass an entire epoch—considered apt to describe the highly ornate and at times bizarre characteristics of architecture, visual arts, and music. It is therefore not surprising that the first musicologists who studied the violin sonatas of Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli were at a loss as how to evaluate this frequently bizarre and consequently utterly “Baroque” music. It took until the final quarter of the 20th century, in the wake of the intensive preoccupation with Early Music within the framework of historically informed performance practice, for the music-historical significance of these works to become apparent. These sonatas form a link between the virtuoso Italian instrumental style of the Early Baroque and the violin music of the High Baroque in southern Germany and Austria, culminating in the music of composers such as Schmelzer and Biber. Pandolfi Mealli long remained a somewhat obscure figure, chiefly because so few details of his biography were accessible. He was really only known for his two collections of sonatas Op. 3 and Op. 4, which were printed by Michael Wagner in Innsbruck in 1660, and for his employment as a chamber musician in the ensemble at the court of the Archduke Ferdinand Karl of Austrian-Tyrol and his wife Anna de’ Medici.

At the beginning of the new millennium, the Italian violinist and musicologist Fabrizio Longo presented the findings of his research into this violin virtuoso and composer. According to Longo, Giovanni Antonio was born as Domenico Pandolfi in Montepulciano, Tuscany, in 1624. A half-brother is documented as having been a castrato at the royal Polish court, and music must therefore have played a certain role in the family. After the death of his father, Domenico moved with his mother Verginia Bartalini to Venice where another half-brother already lived. Nothing is known about Pandolfi Mealli’s musical training and career before the year 1660. It is highly likely that he had already published works prior to this date as the collections printed in Innsbruck are his Opp. 3 and 4: Opp. 1 and 2 have been lost. Pandolfi Mealli must have aspired to a religious career at a certain unknown point during his lifetime, but we do not know whether his name change had anything to do with his ordination as a priest. The entry in the Innsbruck publications identifies the violinist as Don Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli; he therefore appears to have assumed the surname of his maternal half-brothers. This dubious change of name is one of the many larger and smaller inconsistencies in Pandolfi Mealli’s biography—as a secular priest (as implied by the title “D[on]”), he would normally have retained his baptismal name.

Pandolfi Mealli was active at the Innsbruck court by 1660 at the latest, in the dedication year of the sonatas for the Tyrolean regents. It could be imagined that the two collections of works served as a musical “letter of recommendation,” but on the title page of the printed editions, Pandolfi Mealli is already described as “Musico del Serenissimo Ferdinando Carlo Arciduca d’Austria.” The “foreign musicians” in Innsbruck were directed by the famous opera composer Antonio Cesti, and their primary performance duties were in the theater—Ferdinand Karl and Anna were “mad about opera” and spared no expenses for the magnificent musical and theatrical performances based on Italian models. Like many of his colleagues, Pandolfi Mealli was most probably dismissed following the death of Archduke Ferdinand Karl in 1662: the new ruler, Archduke Sigismund Franz, was forced to undertake economic measures due to the extravagance of his predecessor that also affected the music at court. In 1669, we rediscover a Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi in Messina as a first violinist in the chapel of the Senate of the Cathedral, who was the author of the collection Sonate cioe balletti, sarabande, correnti, passacagli, capriccetti, e una trombetta a uno e dui violini con la terza parte della viola a beneplacito, published in Rome in 1669. He was forced to leave Messina in haste after having murdered a castrato colleague of the chapel. He initially fled to France and subsequently found a position in the Royal Chapel in Madrid in 1678 where he also appears to have died in 1687.

These are the facts that Fabrizio Longo has collected within the framework of his commendable research into Pandolfi Mealli. Whether this paltry information is enough to fabricate a compelling story is doubtful, particularly as so many inconsistencies remain unsolved. On top of the dubious change of name, the sonatas of Don Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi from Messina are not allotted opus numbers and stylistically have little in common with the Innsbruck sonatas. How could Pandolfi Mealli have missed the chance of building on the strength of his Innsbruck collections and continuing the sequence of opus numbering—and why is there nothing of his unmistakable stylistic extravagance in the simple dance movements printed in Rome? Could there have been two different individuals with (almost) identical names? The facts are unfortunately too meagre to bring any certainty. The biography of the violinist would naturally gain a gruesome fascination through his heinous crime, but even without any criminal dealings, Pandolfi Mealli still remains a fascinating figure in European musical history and forms a bridge between Italy and the Alpine region.

Let us therefore turn to the Sonatas Opp. 3 and 4. The first collection was dedicated to the crown princess Anna de’ Medici and the second to her husband, Archduke Ferdinand Karl, who together transformed Innsbruck into an international hub of courtly musical culture. They were fortunate to have employed Antonio Cesti as the rising star of Italian opera in 1652. During the following years, he composed operas exclusively for Innsbruck and directed the Italianate court ensemble, an elite group including numerous musicians with an international reputation. Among the individuals employed in Innsbruck were the violin virtuoso and composer Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani and his cousin Antonio, an organist and composer, the Roman violinist Roberta Sabbatini (called “Roberta del Violino”), the English virtuoso viol player William Young, and the master violinmaker Jakob Stainer as “retainer of the archduke.” It is fascinating to imagine that Pandolfi Mealli could have performed his cutting-edge sonatas ahead of their time on the no less modern and extraordinarily fine-toned instruments created by Stainer… The glorious quality of musical performances at the Innsbruck court delighted such illustrious guests as the Swedish Queen Christina who officially marked her conversion to the Catholic faith in the Innsbruck court church in 1655. Ferdinand Karl celebrated this occasion with a performance of the festive opera L’Argia by Cesti. Christina returned to the court in 1669 and was honored by the performance of a different opera. The operatic stars of the day sang in Innsbruck, including Anna Renzi, Monteverdi’s first Ottavia. Music was performed day and night at court: the public church services at court were embellished with magnificent music, music was played both during meals at the royal table and in private settings, dances were organized, and no festival was complete without music.

Pandolfi Mealli specifies the framework for the performances of his sonatas in their title: they are suitable per chiesa e camera, appropriate both in the church and as chamber music in the royal chambers. From a formal aspect, these works consist of free sequences of contrasting sections in a variety of tempos and musical structures. Typical characteristics include extended pedal points above which the virtuoso figure work of the violin unfold. These extended pedal points frequently created acerbic dissonances, and these contrasts and surprising effects were part of Pandolfi Mealli’s favored artistic inventions and characterize his personal style. These types of effects and the free improvisatory style of figuration are familiar from the stylus phantasticus from the first half of the 17th century, which was shaped by composers including Girolamo Frescobaldi und Johann Jakob Froberger and is also so characteristic of the music of Heinrich lgnaz Franz Biber.

All these sonatas were given special names. Here Pandolfi Mealli was referencing individuals within his closer and wider circles (this was a customary practice particularly in Lombardy), as this list shows:

Opus 3

Sonata 1 La Stella—Benedetto Stella, Prior of the Cistercian monastery San Giovanni Battista in Perugia

Sonata 2 La Cesta—Antonio Cesti, chamber music director in Innsbruck, opera composer

Sonata 3 La Melana—Antonio Melani, court singer in Innsbruck

Sonata 4 La Castella—Antonio Castelli, court organist in Innsbruck

Sonata 5 La Clemente—Clemente Antoni, castrato, court singer in Innsbruck

Sonata 6 La Sabbatina—either Pompeo Sabbatini, castrato and court singer in Innsbruck, or Roberta Sabbatini “del violino,” violin virtuoso and chamber musician in lnnsbruck

Opus 4

Sonata 1 La Bernabea—Giuseppe Bernabei

Sonata 2 La Viviana—Antonio Viviani, court chaplain and court organist in Innsbruck

Sonata 3 La Monella—Romanesca Felippo Bombaglia, castrato, court singer in Innsbruck

Sonata 4 La Biancuccia—Giovanni Jacopo Biancucci, castrato, court singer in Innsbruck

Sonata 5 La Stella—Benedetto Stella, Prior of the Cistercian monastery San Giovanni Battista in Perugia

Sonata 6 La Vinciolina—Teodora Vincioli, aristocratic patron from Perugia

What is particularly striking is the double dedication to the Prior of the Cistercian monastery Benedetto Stella and the dedication to the aristocrat Teodora Vincioli. Both were active in Perugia, where Pandolfi Mealli also appears to have spent some time—another aspect of his life requiring closer examination. Perugia is not very far from Montepulciano, the place of his birth. In light of these dedications, the sonatas by Giovanni Antonio Pandolfl Mealli can be viewed as a multifarious homage to the court music ensemble in Innsbruck and his colleagues, its distinguished members.

Franz Gratl holds a PhD in musicology and since 2007 has been curator of the music collection at Tiroler Landesmuseums Ferdinandeum in Innsbruck.

Translation: Lindsay Chalmers-Gerbracht

This essay was originally published in the booklet accompanying Daniel Sepec’s recording of the sonatas by Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli for Coviello Classics. Used by permission.

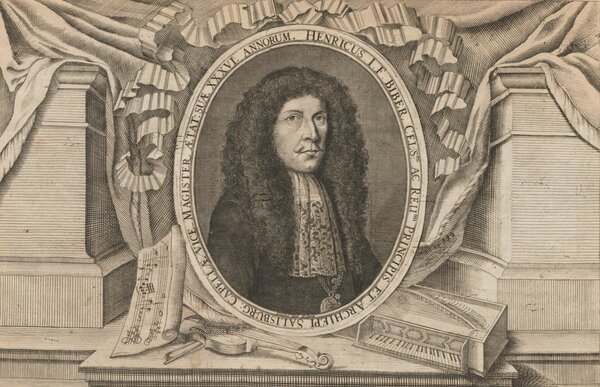

Portrait of Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber in the first edition his 1681 Violin Sonatas

Border Crossings

Considerable geographical barriers notwithstanding, cultural exchange has defined relations between northern and southern Europe for centuries. Although none of the other composers represented on tonight’s program was directly linked to Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli, all five were part of an international web of relationships and reciprocal influences that made 17th-century Europe a tightly interconnected, and remarkably fertile, musical ecosystem.

By Harry Haskell

Border Crossings

Music by Schmelzer, Bonizzi, Kapsberger, and Biber

Considerable geographical barriers notwithstanding, cultural exchange has defined relations between northern and southern Europe for centuries. When the English music editor Nicholas Yonge published the first volume of Musica Transalpina—a pathbreaking anthology of Italian madrigals—in 1588, composers and performers from Italy had long been making their way across the Alps to work in the courts and chapels of the Habsburg monarchy. The transalpine route was a two-way street: scores of Austrian and German musicians headed south to Italy, which Heinrich Schütz, a disciple of the Venetian master Giovanni Gabrieli, famously called “the true university of music.” Although none of the other composers represented on tonight’s program was directly linked to Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli, all five were part of an international web of relationships and reciprocal influences that made 17th-century Europe a tightly interconnected, and remarkably fertile, musical ecosystem.

Renowned far and wide as a violin virtuoso, Johann Heinrich Schmelzer was based at the imperial court in Vienna, where the musical establishment also included such notable Italian expatriates as Giovanni Felipe Sances, Antonio Bertali, and Antonio Draghi. The bravura idiom of his D-major Sonata, published in 1664, owes much to the brilliantly extroverted Italian style of instrumental music that Arcangelo Corelli and Antonio Vivaldi would come to epitomize in the ensuing decades. Cast as a chain of increasingly elaborate variations over a repeating four-note figure in the continuo accompaniment, the Sonata highlights Schmelzer’s innovative bowing techniques and daringly unconventional harmonies. Vincenzo Bonizzi’s instrumental embellishment of Adriaen Willaert’s chanson “Jouissance vous donneray” is similarly structured as a set of ornate “divisions” supported by a slower-moving bass line. Bonizzi spent his entire life in and around Parma, where he served for three decades as organist and maestro di cappella at the court of the music-loving Lucrezia d’Este, duchess of Urbino. Lucrezia employed a celebrated trio of viol-playing sisters known as the “concerto delle dame” (consort of ladies), one of whom evidently adopted the viola bastarda, a short-lived cousin of the bass viol for which Bonizzi’s piece was written.

Born in Venice, the son of a German nobleman, Johann Hieronymus (aka Giovanni Girolamo) Kapsberger was closely associated with the emergence of the lute and its long-necked cousin, the theorbo (or archlute), as solo instruments at the turn of the 17th century. The three pieces to be heard tonight appeared in 1611 in his first collection of lute music. Kapsberger’s highly idiosyncratic voice is characterized by an abundance of trills and other ornaments, syncopated rhythms, dramatic outbursts, and lengthy passages in so-called broken style, in which rapid arpeggiated figurations are anchored by intense, searching harmonies. No less bracingly virtuosic is Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber’s Sonata in F major for violin and continuo of 1681, a dazzling showpiece replete with double stops, fast repeated notes, athletic leaps, and tricky string crossings. Bohemian by birth, Biber pursued his career within the sprawling, polyglot empire of the Austrian Habsburgs. Like Schmelzer, with whom he may have studied, he embraced the florid, richly melodic Italian style exemplified by his contemporary and fellow composer-violinist Corelli. Biber’s cutting-edge violin techniques, timbral effects, and tunings are characteristic of the “fantastic style” (stylus phantasticus), which the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher described in 1650 as “the most free and unfettered method of composition, bound to nothing, neither to words, nor to a harmonic subject.”

—Harry Haskell

The Artists

Daniel Sepec

Violin

Daniel Sepec studied with Dieter Vorholz in Frankfurt and Gerhard Schulz in Vienna and completed his training by attending masterclasses with Sandor Végh and the Alban Berg Quartett. He has been concertmaster of the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen since 1993 and regularly appears with the orchestra as a soloist. Under his musical direction, the ensemble has recorded works by Johann Sebastian Bach and Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. He has also performed as a soloist with the Academy of Ancient Music under Christopher Hogwood, the Wiener Akademie under Martin Haselböck, and the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées under Philippe Herreweghe, and has appeared as guest concertmaster with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe under Claudio Abbado, Camerata Salzburg, and Ensemble Oriol. He regularly performs with the period-instrument Balthasar Neumann Ensemble under the direction of Thomas Hengelbrock. As a member of the Arcanto Quartett, Daniel Sepec has recorded string quartets by Mozart, Brahms, Debussy, Ravel, Bartók, and Dutilleux. His recording of Biber’s “Mystery” Sonatas won the 2011 German Record Critics’ Prize. Daniel Sepec has been a professor at the Lübeck Musikhochschule since 2014.

April 2025

Hille Perl

Viola da gamba

Born in Bremen, Hille Perl started playing the viola da gamba at the age of five and is among today’s most renowned viol players internationally. She has performed throughout Europe as a soloist, with musical partners such as Daniel Sepec, Lee Santana, Michala Petri, Mahan Esfahani, and Avi Avital, and with her ensembles Los Otros, The Sirius Viols, and The Age of Passions. She also appears regularly with leading Early Music ensembles including the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and the Balthasar Neumann Ensemble and has released numerous recordings, several of which were awarded the ECHO Klassik. She has been a professor at her hometown’s University of the Arts since 2002.

April 2025

Lee Santana

Theorbo and Archlute

Lee Santana hails from Florida and first trained as a rock and jazz guitarist. He then switched to the lute, theorbo, and cittern, specializing in Early Music. Among his teachers were Stephen Stubbs and Patrick O’Brien. He has been working as a lutenist and composer throughout Europe since 1984, appearing regularly at major festivals and concert halls and collaborating with artists and ensembles such as the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Dorothee Mields, Petra Müllejans, Daniel Sepec, Sasha Waltz, and Hille Perl. In recent years, Lee Santana has also been active as a composer.

April 2025

Michael Behringer

Harpsichord and Organ

Michael Behringer studied church music in Freiburg, organ with Michael Radulescu in Vienna, and harpsichord with Ton Koopman in Amsterdam. He has appeared internationally as a continuo player as well as soloist with many leading early-music ensembles, including most recently Hespèrion XXI under the direction of Jordi Savall, the Balthasar Neumann Ensemble under Thomas Hengelbrock, and the Freiburger Barockorchester. He can be heard on recordings of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Musical Offering, Clavierbüchlein, and viol sonatas, among others, and has appeared with the Berliner Philharmoniker under Sir Simon Rattle in St. John’s Passion. He taught harpsichord and basso continuo at the Freiburg Musikhochschule until 2022.

April 2025