Program

Works by

John Dowland

Franz Schubert

Pauline Viardot

Jules Massenet

Bob Dylan

Laurie Anderson

Hans Abrahamsen

Detlev Glanert

Thomas Adès

Cassandra Miller

Sasha Scott

Jules Massenet (1842–1912)

Ô Souverain, ô juge, ô père

Rodrigue’s aria from the opera Le Cid (1883–5)

John Dowland (1563–1626)

Praeludium

Come Again

Think’st Thou Then by Thy Feigning

Come, Heavy Sleep

from First Booke of Songes (1597)

Sasha Scott (*2002)

1000 parts of you (2024)

Commissioned by Wigmore Hall and Richard Cauldwell

***

Detlev Glanert (*1960)

Insel der Düfte

from Orlando-Lieder (2004)

Thomas Adès (*1971)

Over the Sea

Blanca's scene from the opera The Exterminating Angel (2015–6)

Detlev Glanert

Hexensabbat

from Orlando-Lieder

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Einsamkeit

from Winterreise D 911 (1827)

Detlev Glanert

Lied der Wehmut

from Orlando-Lieder

Thomas Adès

Habanera

Leonora's aria from The Exterminating Angel

Intermission

Detlev Glanert

Orlandos Traum

Lied vom Meer

Der Hippogryph

from Orlando-Lieder

Cassandra Miller (*1976)

Dream Memorandum (“It Reminded Me of the Truth”) (2024)

Commissioned by the Borletti-Buitoni Trust

Hans Abrahamsen (*1952)

See the Limpid Spring

from Two Inger Christensen Songs (2017)

Franz Schubert

So lasst mich scheinen D 877/3 (1826)

***

John Dowland

Orlando Sleepeth

Pauline Viardot (1821–1910)

Aimez-moi (1886)

Bob Dylan (*1941)

Masters of War

Based on a traditional arranged by Jean Ritchie (1962–3)

Laurie Anderson (*1947)

O Superman (for Massenet) (1981)

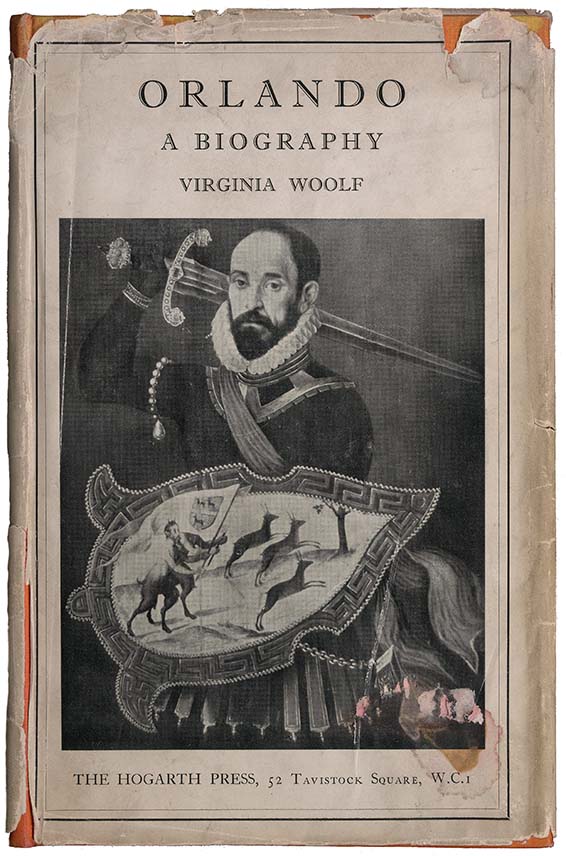

Cover of the first edition of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, London 1928

Orlando as Collage

Why bother with programming or “curation” at all? It is a question that has appeared many times in my thoughts and in conversations with friends, colleagues. A response: to digest, to triangulate, to make connections in unlikely spaces.

A Note from Ema Nikolovska

Orlando as Collage

A Note from Ema Nikolovska

Why bother with programming or “curation” at all?

It is a question that has appeared many times in my thoughts and in conversations with friends, colleagues. A response: to digest, to triangulate, to make connections in unlikely spaces.

Flurries of sound and images are launched onto our senses daily, often uncomfortably although we are used to it by now. Virginia Woolf ’s character Orlando, having lived for centuries, expresses the overwhelming spirit of the modern age when she’s speeding through London in a convertible in 1928: “Nothing could be seen whole or read from start to finish. What was seen begun—like two friends starting to meet each other across the street—was never seen ended. After twenty minutes the body and mind were like scraps of torn paper tumbling from a sack and, indeed, the process of motoring fast out of London so much resembles the chopping up small of identity which precedes unconsciousness and perhaps death itself that it is an open question in what sense Orlando can be said to have existed at the present moment.”

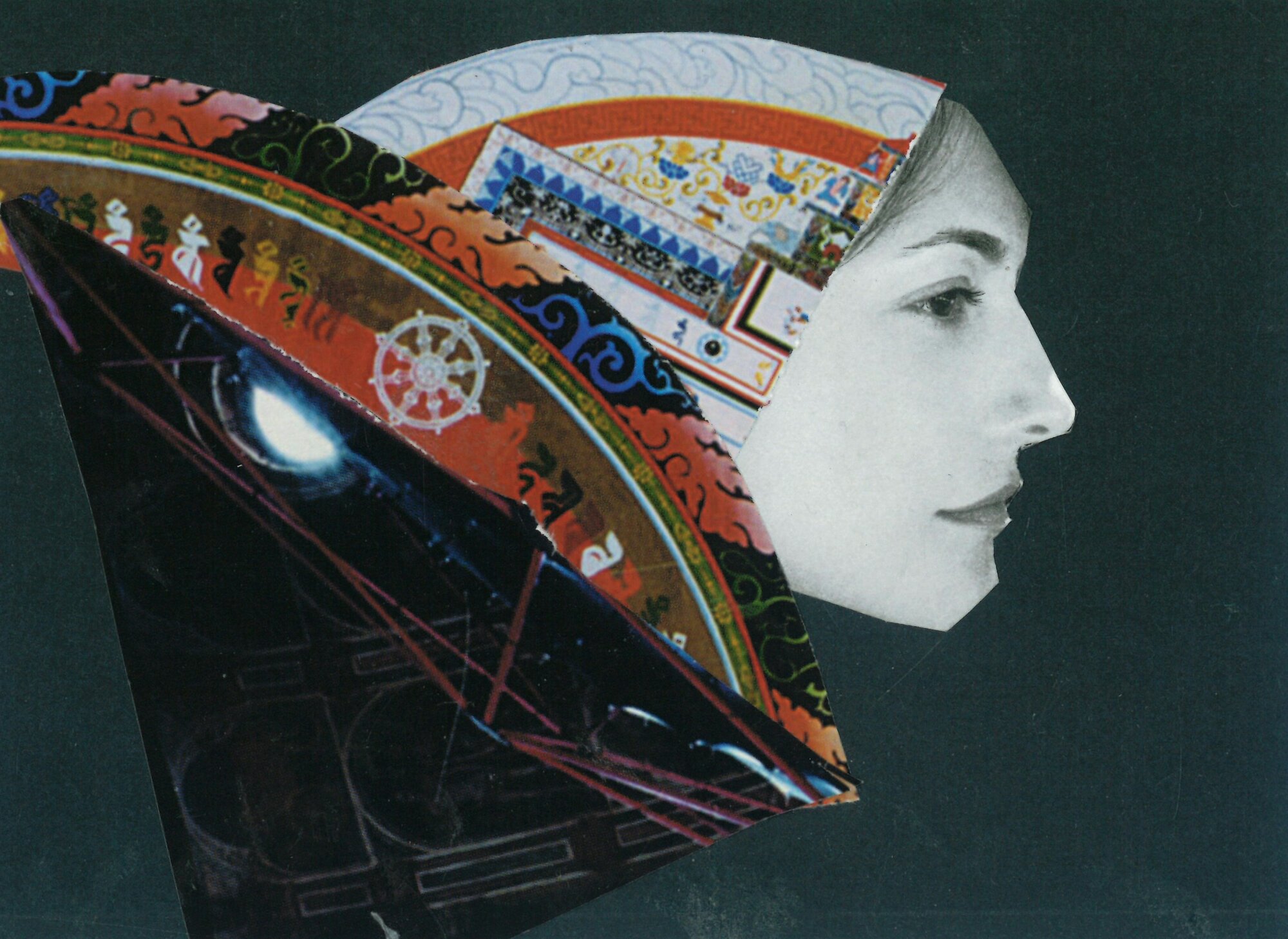

Such growing stimuli inevitably become ingredients for experiments in collaging, and this is where curation becomes fun and exciting. Being alive in 2025 means we have access to many time periods of stories and sounds simultaneously, and a central curiosity in my work with Sean (as a duo and for our individual projects) is: what happens when these sounds coexist? The “ancient” and “modern” are in dialogue, sewn together in this sound quilt, as are the realistic and uncanny—the familiar becomes unfamiliar and vice versa. A sort of “third entity” emerges from the alchemical interaction of these found objects.

In our program, we play around with many Orlandos from various sources (often relating to knights, adventurers, troubadours) and indeed we ourselves become Orlandos through the process. At the root of it all is Virginia Woolf ’s Orlando: a character who has inspired generations of readers (and us) with their sheer optimism, curiosity, openness to the world, playfulness, and audacity. The mutability of our identity, the “thousands of selves” within remind us that we will always be a surprise to ourselves and also, to allow surprises from others; the spirit of this project is to find those surprises.

Woolf’s novel was itself experimental, thwarting the concept of the western novel and approach to telling stories, a revolution in post-modern literature—almost a parody on biography and any linear concept of “self,” and additionally a stream-of-consciousness whirlwind. Such structures and ideas from Woolf are a fertile playground for programming that is abstract enough to involve the audience’s imaginations as active participants, so they can fill in certain prompts for story and sense as they move through the experience.

Sean and I have grown in our programming practices through following the instincts that emerged from our exploration of this character, scavenging for sound worlds and poetry that could be relevant: we have expanded our ideas about what 70 minutes of music can be, morphing into this hybrid of concert and theater, electric and acoustic, and inventing ways to create halls of mirrors, illusions, elisions. How fitting that it was in London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood (where Virginia Woolf lived and worked for a time) where we first met! Woolf herself was a master curator, engaging with rhythm of language, pacing of images and poetry, and her literary collages have left a huge impression on our creative practice.

Woolf ’s Orlando reminds us that the only boundaries and binaries that exist are the ones we create for ourselves; our imagination has the power to restrict, or to connect and extrapolate. Orlando’s story (whether it is the character as seen by Woolf, Ludovico Ariosto, or ancient French poetry) is a celebration of the infinite potential for adventure in any moment, the unreality of time and space, and the freedom that is to be found between our ears.

Dreaming Orlando

Ema and I met when living together in London. We made music together for the first time one evening in 2019, working through the songs that we had found. Whiteboards and post-its were useful, but engaging with the general flavor of the Orlando tales was even more important than reflecting details accurately.

A Note from Sean Shibe

Dreaming Orlando

A Note from Sean Shibe

Ema and I met when living together in London, and we made music together for the first time one evening in 2019. In a dark subterranean setting, our smiles grew as we worked through the songs that we had found, with murmurs of “yeah,” “nice,” “right on…”

Whiteboards and post-its were useful, but engaging with the general flavor of the Orlando tales was even more important than reflecting details accurately. When comparing and selecting highlights from a plethora of tellings of an epic, one cannot render a full composite—at least not in a single evening recital. What we show is where those tellings took us.

The version we love most is Virginia Woolf ’s fantastical romp through space and time, described through scenes that feel like dreams. At one point Orlando wakes up, realizes England has become damp, and decides to go to Constantinople. And why not?! She (both Woolf and Orlando, I suppose) insists; and we are compelled to obey a new set of rules. Characters and creatures explode into scenes without invitation or reason. A type of chaos is embraced. Through Woolf we found the way forward. Logic is restriction. Keep moving.

The planning periods, I feel, reflected the array of place and period and person I experienced when reading Woolf’s Orlando for the first time. Meeting Sebastian Blue (who had a tattoo of Orlando Gibbons on their arm, wore a leather flight cap, and looked after the nunnerly crown of Hildegard) in Bern; watching Cassandra Miller and Ema sing and make bird noises to one another while I lay on the ground in an attic; melodica duet listening sessions rendered feverish through flu and Carragelose nasal spray; all of this felt right. I remember the cold; cars full of bags and instruments trundling around dimly lit Victorian streets; and the mind-fog of trying to wrestle something ungraspable into logic. Orlando had been in us from our first musical meeting, but actually contorting our vestigial ideas into a full and coherent program took a huge and—at least for myself—unprecedented effort.

Our Orlando is therefore out of necessity not a full history (listening to anyone’s dream in detail is a terrible experience), but a sort of turbo- dream. It is a program put together during meetings that felt otherworldly. Cassandra has even written a piece for us that remembers our own dreams. In retrospect this was, perhaps, inevitable. Our Orlando is chaotic, in part because the tale is chaotic, but also because Ema and I are. We want to tell you more, and when we can we will.

A Kaleidoscopic Existence

The knight immortal, the troubadour ever-changing, the lover constant: Orlando adventures in all their/her/his forms, uncovering who they truly are. Tonight’s program explores the non-linear journey between the multiple iterations of Orlando through disparate times, genders, and media, inspired by written stories such as the Old French Chanson de Roland, Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, and Virginia Woolf ’s Orlando: A Biography.

Essay by Aiden Feltkamp

A Kaleidoscopic Existence

Musical Portraits of Orlando

Aiden Feltkamp

The knight immortal, the troubadour ever-changing, the lover constant: Orlando adventures in all their/her/his forms, uncovering who they truly are. Tonight’s program explores the non-linear journey between the multiple iterations of Orlando through disparate times, genders, and media, inspired by written stories such as the Old French Chanson de Roland, Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, and Virginia Woolf ’s Orlando: A Biography.

Orlando’s experience with war begins with the Chanson de Roland (written c. 1040), one of the oldest surviving works of French literature, and continues with his part in Orlando furioso (1532). These poems focus on the duties of a knight, as well as courtly love and the chivalrous adventures that ensue. Virginia Woolf forces Orlando to consider his identity in her 1928 novel, making him both long-lived and genderfluid. Inspired by her first female lover and fellow writer, Vita Sackville-West, Woolf created an Orlando who not only shifts from a man into a woman and steps up in social class from a court page to a noblewoman, but who explores their gender expression and sexuality. The novel follows Orlando’s centuries-spanning adventures through both physical countries and metaphysical ways of being.

Ema Nikolovska and Sean Shibe’s program follows Orlando’s kaleidoscopic existence via the four musical signposts of Sasha Scott’s 1000 parts of you, Cassandra Miller’s Dream Memorandum, Detlev Glanert’s Orlando-Lieder, and Laurie Anderson’s O Superman. Along the way, we touch upon music by Dowland, Massenet, Bob Dylan, and others.

Both Sasha Scott and Cassandra Miller contend with Orlando’s identity in their works (both premiered in 2024), deriving inspiration from Woolf ’s novel. 1000 parts of you by Scott, a Londoner and recent graduate from the Royal College of Music, mirrors her cover of O Superman, employing voice, guitar, and electronics. About this piece, she said, “[Chapter 6 of Orlando] led me to contemplate how we all as humans have what feels like thousands of different selves and parts of us, which all make us who we are. When I was thinking about this, I visited the exhibition Infinity Mirror Rooms by Yayoi Kusama. I was really moved and struck by the infinitive amount of reflections there were in the mirrored room, and how it almost felt like a simulation of Orlando’s introspection. I wanted the sound world to feel infinitive and contemplative, yet consuming and overwhelming.”

Miller, a Canadian composer and previous Associate Head of Composition at London’s Guildhall School of Music & Drama, created her piece, Dream Memorandum (“It Reminded Me of the Truth”), from the voice memo of her conversation with Ema Nikolovska about the overarching themes of Woolf ’s novel. Speaking about her process, Miller said, “I asked Ema to re-learn excerpts of her voice memos to me, and to speak them in concert accompanied by Sean. I find the sound of Ema’s voice to be magical, evocative, and intelligent—and, fortunately for the transcription process, quite tonal. Her flights of insight manifest in an effervescent F major, and her most profound reflections have a rich D-minor cadence.”

While adventuring the musical landscape, we continuously return to Detlev Glanert’s Orlando-Lieder. This set of songs explores facets of Orlando’s personality while providing a musical scaffolding for the entire recital. The texts, although inspired by Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, are new poems by writers Margareth Obexer and Angela di Ciriaco-Sussdorff. This work had its complete world premiere in Berlin in 2005, with Aron Brieger and Juliane Tief. Glanert’s propensity for harmonic complexity in his vocal work shines through these songs, although he swaps his usually dense soundscape for the sparse narrative style common to the troubadours and trobairitz of the Middle Ages. The voice moves freely over the lute-like accompaniment of the guitar, Glanert’s emotion-forward compositional voice lending itself well to these texts that focus on passion and adventure.

This troubadour-esque sound serves as a connective thread throughout the recital, exemplified by Dowland’s work and coloring the wartime songs of Bob Dylan and Laurie Anderson. When placed alongside Dylan’s Masters of War, a Cold War protest song from 1963, Anderson’s O Superman displays the effects of war on Orlando’s identity and hampered ability to create community. Having started as an indie avant-garde artist, Anderson burst onto the commercial scene with O Superman, taking the number two spot on the UK singles chart in 1981. The song began as part of United States, an eight-hour stage work that spanned two evenings and included musical numbers alongside purely visual segments, spoken word pieces, and animated vignettes. Both the stage work and the song explore life in the United States, with the song focusing on how new technology can change communication between individuals during wartime. This song is sometimes called O Superman (for Massenet) because Anderson was inspired by the aria “Ô souverain, ô juge, ô père” from Massenet’s opera Le Cid. The opening line of the piece (“O Superman, O Judge, O Mom and Dad”) mirrors the translated opening line of Massenet’s aria (“O sovereign lord, O judge, O father”), but the text diverges after that. The original recording of O Superman utilizes looping electronics and a vocoder, allowing Anderson’s voice to serve as both a constant beat and an accompanying, chordal Greek chorus. This cover version, created by Sasha Scott, emulates the electronic accompaniment of the original while adding an acoustic element through the use of guitar. Orlando’s adventure continues through and beyond this program, their identity changing as they repeatedly reflect upon it. Who and what will they become next?

Aiden K. Feltkamp began their artistic life at the age of five in New York playing a quarter-size cello and now they create opera, poetry, and prose as a writer and performer. Their work centers on stories from marginalized communities and spans the serious and the ridiculous, the real and the surreal. Most recently, they wrote the libretto for Emily & Sue, an opera about Emily Dickinson’s queerness, and curated New Music Shelf ’s award-winning New Music Anthology for Trans & Nonbinary Voices, Vol. 1.

The Artists

Ema Nikolovska

Mezzo-soprano

Born in Macedonia, Ema Nikolovska grew up in Toronto, where she studied voice privately with Helga Tucker and completed undergraduate studies as a violinist at the Glenn Gould School. She received her master’s degree as a mezzo-soprano from London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where her teachers included Rudolf Piernay and Susan McCulloch. In 2019 she was named a BBC New Generation Artist and joined the Young Classical Artists Trust; in 2022 she won the renowned Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award. From 2020 to 2022, she was a member of the opera studio at Berlin’s Staatsoper Unter den Linden, singing leading roles in Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel and Christian Jost’s Die arabische Nacht, among others. She returned to the company in 2023 for her role debut as Octavian in Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier. Recent concert appearances include Stravinsky’s Les Noces with the Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, Claude Vivier’s Wo bist du Licht! with the Orchestre philharmonique de Radio France, and Scriabin’s Symphony No. 1 with the Danish National Symphony Orchestra. Song recitals, which form a central part of her artistic activities, have taken her to London’s Wigmore Hall, Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie, the Berlin Konzerthaus, Carnegie’s Weill Recital Hall in New York, and to the festivals of Heidelberg, Verbier, and Aldeburgh. A regular guest at the Pierre Boulez Saal, Ema Nikolovska has been heard here several times as part of Schubert Week.

March 2025

Sean Shibe

Guitar, Electric Guitar, Electronics

Sean Shibe studied with Allan Neave at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, with Paolo Pegoraro in Italy, and at the University of the Arts in Graz. He teaches as a professor at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London and is a regular guest at renowned venues such as Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie, the Philharmonie de Paris, the Vienna Konzerthaus, and Frankfurt’s Alte Oper. In addition to solo performances, he collaborates with a wide range of musicians and ensembles, including the Britten Sinfonia, the Dunedin Consort, the Danish String Quartet, tenor Allan Clayton, and performance artist Marina Abramović. He frequently commissions new compositions for guitar and has premiered works by Thomas Adès, David Fennessy, Shiva Feshareki, and Julia Wolfe, among others. This current season, he performs Pierre Boulez’s Le Marteau sans maître as Artist in Residence at London’s Wigmore Hall, tours the U.S. with tenor Karim Sulayman, and premieres new guitar concertos by Cassandra Miller and Mark Simpson with the Australian Chamber Orchestra and at the BBC Proms, respectively.

March 2025