Jörg Widmann Clarinet, Piano

Jens Harzer Recitation

Program

Paul Celan

Lichttöne: Selected Poems

Reading in German

Luciano Berio

Lied for Solo Clarinet

Mark Andre

Atemwind for Solo Clarinet

Jörg Widmann

Excerpts from Idyll und Abgrund for Piano

Paul Celan (1920–1970)

Selected Poems

Reading in German

Luciano Berio (1925–2003)

Lied for Solo Clarinet (1983)

Beginning • Home • Mother

Ich lotse dich

Zähle die Mandeln

Heimkehr (from Sprachgitter)

Landschaft (from Frühe Gedichte)

Wasser und Feuer

Der Reisekamerad

Warum dieses jähe Zuhause

Jörg Widmann (*1973)

Excerpts from Idyll und Abgrund

Six Schubert Reminiscences for Piano (2009)

I. Irreal, von fern

Depth • Verticality • Hazard

Lob der Ferne

Das Wort zum Zur-Tiefe-Gehn

In Mundhöhe

Ich hörte sagen

Schwarz

Tübingen, Jänner

Es stand

from Idyll und Abgrund

VI. Traurig, desolat

Prayer • Being Jewish • Grappling with God

Rebleute

Tenebrae

Die Pole

Psalm

Zürich, Zum Storchen

Eine Gauner- und Ganovenweise

Schibboleth

Denk dir

Nähe der Gräber

from Idyll und Abgrund

IV. Scherzando

Love • Sex • Women

Abend

Die Jahre von dir zu mir

Köln, Am Hof

Erinnerung an Frankreich

Die Hand voller Stunden

In Ägypten

Air

Wo ich

Marc Andre (*1964)

Atemwind for Solo Clarinet (2016–17)

Psychiatry • Delusion • Illegibility • End

Ich habe Bambus geschnitten

Ein Holzstern

Fadensonnen

Es wird

Unlesbarkeit

Krokus

Einmal (from Atemwende)

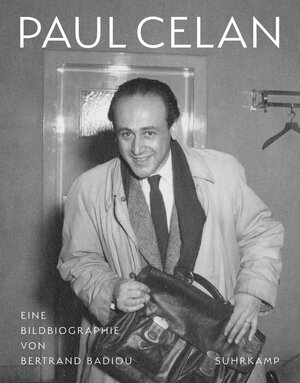

Paul Celan, 1955 (© joint private estate of Paul Celan and Gisèle Celan-Lestrange, Paris. Private property of Éric Celan; reproduced with kind permission by Suhrkamp Verlag)

Reading Celan

“For a long time, I didn’t exactly feel called upon to read Celan in front of an audience. On the other hand, my advantage was being quite open-minded as a reader. As far as the hermetic, indecipherable element in Celan’s writing is concerned, I was fortunate to never feel overwhelmed by it as a reader, because there was always something there that seemed clear to me.”

A Conversation with Jens Hazer

Reading Celan

A Conversation with Jens Harzer

This is not your first reading of Paul Celan’s poetry, and you have also recorded audiobook versions of his poems and his correspondence with Ingeborg Bachmann. How did your relationship with this poet, generally regarded as somewhat difficult, develop?

For a long time, I didn’t exactly feel called upon to do this at all—reading Celan in front of an audience. On the other hand, my advantage was being quite open-minded as a reader. As far as the hermetic, indecipherable element in Celan’s writing is concerned, I was fortunate to never feel overwhelmed by it as a reader, because there was always something there that seemed clear to me—even when I began to get into it, at the age of 18 or 19. Very early on, I came across that passage in one of his famous speeches where he says that the poem seeks a counterpart, on its way to a “you.” I certainly didn’t entirely comprehend that when I was young, but what I did understand, as a reader, was that when those leaps, those rifts occur between the various images, I’m called upon to complete things in my own mind. So I never had a problem with Celan; nor was I ever “afraid” of his weight, this hermeticism. Some time ago, shortly before the correspondence between Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann was published in German, Suhrkamp, the publisher, approached me with the idea of creating several readings and an audiobook from it. And I thought: perhaps I can make use of the fact that as a reader, even when I didn’t understand him, I always felt an affection for Celan and had the impression that I might actually be the counterpart of the poem, one among many, hopefully, reading it. I try to combine this personal passion with an approach of getting as close as possible to the material and the author.

What does that mean for the way you read it?

As a reciter, my only job is to do as much as I can so that the poems may be unlocked for the listener, perhaps not so much from the vantage point of knowledge, but of linguistic form, of syntax—the relationship between verbs and nouns, for example, to enable the listener to absorb a sentence by hearing. In other words: as a reciter, my goal is to present the texts as much as possible in terms of graspable images, so that the poems might open up, with all their indecipherable elements. The point is not to overwhelm. Even when I recite, I see myself mainly as a reader. At the same time, I’m not alone—adding Jörg Widmann’s music expands this entire cosmos by many aspects, some of them quite different.

How did you select the poems for this program?

Jörg and I came up with various thematic sections, to make sure that the texts, some of which are very short, wouldn’t stand too much on their own. Several terms emerged. The first is “Beginning,” the second “Depth/Vertical,” the third “God/Prayer/Being Jewish,” others include “Child/Son,” “Cities,” “Love/Sex/Women,” and “End/Psychiatric Ward.” We also tried to consciously avoid the very famous poems. So we ended up with a mix of the less familiar and the well-known. For example, Celan wrote very beautiful love poems. You can’t get around Die Jahre von dir zu mir, or In Ägypten, a poem addressed to Ingeborg Bachmann. In the section “Cities,” for example, we have Köln, Am Hof, also written for Bachmann. Or Zürich, Zum Storchen for Nelly Sachs, and finally also Tübingen, Jänner, the Hölderlin poem. But when it comes to one specific issue that’s central to Celan, namely, his wrestling with God, or the absence of God, with the Shoah, and the violent death of his parents and friends, we decided upon a lesser-known poem that’s very dear to my heart. It’s called Rebleute, and it’s from Celan’s late period, written a year before his death. The poem ends: “Die Offenen tragen / den Stein hinterm Aug, / der erkennt dich, / am Sabbath.” (“The open ones carry / the stone behind the eye, / it knows you / come the sabbath.”) Rebleute may be a good example for many of the poems we selected—they are often dark and hermetic, some of them only six or eight lines long. At the same time, these poems open up when you try to very carefully approach them. And perhaps this is how the poem touches upon the “land of the heart,” as Celan tried to describe his utopia of poetry in one of his speeches.

Interview: Martin Wilkening

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

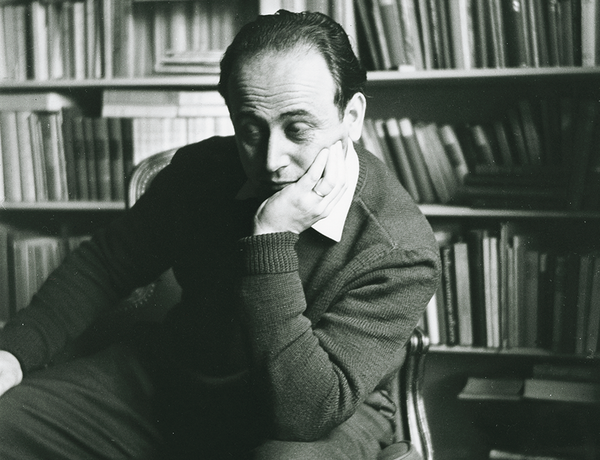

Luciano Berio in the 1950s

Balancing Proximity and Distance

“It was important to us that each element, literature and music, keep its own space. The two are not meant to explain each other; instead, we present this program with the inherent question of whether it can open up spaces where new context or meanings might reveal themselves.”

A Conversation with Jörg Widmann

Balancing Proximity and Distance

A Conversation with Jörg Widmann

What are the ideas behind this program—and how do text and music interact?

It was important to us that each element, literature and music, keep its own space. The two are not meant to explain each other; instead, we present the program with the inherent question of whether it can open up spaces where new context or meanings might reveal themselves. But these are not premeditated. We performed the program once before in Vienna and were both taken by surprise several times.

What kind of surprises were these?

Berio gave his piece the title Lied, “song.” And in my piano pieces, there’s often a folksong-like tone that is then broken up. Celan’s texts invariably are also broken up in a similar way, with excursions, or perhaps I should say intimations, of folk music, a songful style, even if the connotations are different. Celan is very rigid, the contrast with such allusions to song is much sharper, while the musical element in these three compositions flows very freely and unhindered. But it remains a balancing act between proximity and distance, even though they emanate from a single voice, just as the spoken poems.

Among the composers heard tonight, Luciano Berio is the only one who also used texts by Celan in his compositions. The poem Die Posaunenstelle appears in his contribution to a collaborative Requiem project by several composers in Stuttgart; he set Tenebrae as the first piece of his last major composition, Stanze. You have chosen his Lied as a clarinet piece—why not the better-known Sequenza for solo clarinet?

First of all, Lied is performed far too rarely. Of course everyone plays Berio’s Sequenza, not least because it’s so frequently required at major competitions. My opinion may be drastic, but it’s also based on conversations I had with Pierre Boulez about it. To me, the clarinet Sequenza isn’t actually a finished piece. It consists of about three and a half minutes of fantastic music that only Berio could have written—then it wanes, ending with nothing but sustained notes. That ending has no quality of its own, it’s simply unfinished. Boulez told me that Berio had intended to create an expansion through electronics that he wanted to develop at IRCAM. Boulez had scheduled four weeks for this, but Berio wanted to do it within a few days. He couldn’t complete it at the time, and never returned to it, even if the work was published and the score has Berio’s name on it. This is why I refuse to play the piece. As I see it, Lied consists of very similar material. Here, it’s reduced to two printed pages, but it’s completed. It starts with a sequence of two thirds, really like a song. Then there are short, rapid interventions, and so it continues: statement—questioning—statement. The material, its form and length come together here in a wonderful way. As simple as it is, it’s also enigmatic, until the very end. I just love playing this piece.

In recent years, you have developed three pieces together with Mark Andre: a clarinet concerto with orchestra and electronics, a solo piece with complex live electronics that has been heard at the Pierre Boulez Saal in the past, and finally Atemwind, in which the clarinet plays by itself. As with the two previous ones, Andre prefaces this piece with a quote from the Gospel of John, giving it a Biblical, spiritual reference: “The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit…”

In this piece, the reference is realized in purely acoustical terms, without the prerecorded sounds of wind in the Israeli landscape that are part of the other two works. In the Hebrew word ruach or the Greek pneuma, both elements merge, wind and breath—Atemwind, or breath-wind.

I think a piece like this can’t be written at one’s desk, but it can’t be improvised by simply playing the clarinet either. Over many sessions, Mark Andre and I became deeply attuned to each other, and this led to a burst of creativity that simply wouldn’t stop. I don’t know anything comparable to this piece: its barrenness, this reduction, this insistence that every individual note and noise of air must be perceived, and then again a kind of freewheeling up and down within the time structure. There are many different kinds of air sounds, there are places where the air seems to start rattling. Mark calls these “helicopter sounds.” What we developed together are mainly these very fragile multiphonics. They’re destabilized even further by the various playing techniques. Incidentally, that’s something the piece has in common with Berio: instabile is one of the most frequent performance instructions in Lied. This instability is something Mark Andre deliberately seeks out, it’s about disappearance and appearance, about the threshold, also in a theological context. It certainly goes far beyond a simple clarinet piece.

How, specifically, might we imagine this unstable element?

At one point, for example, I play a multiphonic that is fragile to begin with, at a dynamic of quadruple piano. Then I add a trill. The first result is that the upper and the lower note collapse on me. I have to find an approach that resembles a slalom, keeping one line despite the many poles to go around, so that the note doesn’t break. When the composer additionally asks for a semi-air tone, that’s another component on top of all this. Or when he moves from three overtones to five, this transition should be as gradual as possible. For the clarinetist, this effect is extremely fragile to produce, but for the audience it is also very difficult to perceive.

Earlier, you spoke of the song-like or folk music–like inflections in your piano pieces Idyll und Abgrund, which are subtitled “Schubert Reminiscences.” Could you explain that just a bit more?

These reminiscences don’t refer to any particular Schubert pieces; they’re not quotations. At least not in the three pieces I’ll be playing in this concert, namely Nos. 1, 4, and 6. The first is almost a lullaby, but with a psychedelic element. It appears to be very simple, in 3/4 measure and C major, but there’s something wrong there. In the high registers, we hear mixtures and dissonances that call the entire piece into question. No. 4 is cheerful, which may be a nice contrast in the context of this evening, a change from the meaningful texts of the reading and the large-scale piece by Mark Andre. It sounds a bit like a false glockenspiel playing a ländler fantasy that beings to stumble and slides into the wrong keys; there’s whistling involved as well. So its cheerfulness and gaiety is undermined at the same time. The last piece has a very different character: it toys with tonality, tries to come across as light, also by increasing the tempo, but it fails and gets stuck in a pendular movement on the dominant, caught up within its own melancholy. Here, Schubert feels very close, despite the distance.

Interview: Martin Wilkening

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

Dive deeper

On November 20, 2023, Suhrkamp Verlag published the first comprehensive illustrated biography of Paul Celan, which traces the life of the most widely interpreted German-language poet after 1945 with numerous previously unpublished images and extensive excerpts from his as yet unpublished diaries.

The Artists

Jörg Widmann

Clarinet and Piano

Composer, clarinetist, and conductor Jörg Widmann is among the most acclaimed musicians of our time. Born in Munich in 1973, he studied clarinet at his hometown’s Hochschule für Musik und Theater and at the Juilliard School in New York and composition with Kay Westermann, Wilfried Hiller, Hans Werner Henze, and Wolfgang Rihm. As a clarinetist, he is an active chamber musician and regularly performs with artists including Daniel Barenboim, Sir András Schiff, Tabea Zimmermann, and Denis Kozhukhin as well as the Schumann Quartett and the Hagen Quartett. Composers such as Wolfgang Rihm, Aribert Reimann, Mark Andre, and Heinz Holliger have written new works for him. He has been artist and composer in residence at international venues and institutions, among them the Salzburg and Lucerne festivals, the Vienna Konzerthaus, the Cleveland Orchestra, Carnegie Hall, and Cologne’s WDR Symphony. He currently serves as principal guest conductor for the NDR Radiophilharmonie and the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra, and as composer in residence with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic and the Berliner Philharmoniker, for which he is writing a new horn concerto. He also conducts performances with the Bamberg Symphony, the SWR Symphony, and the Bavarian Radio Symphony. Jörg Widmann holds the Edward W. Said Chair for Composition at the Barenboim-Said Akademie and has been closely associated with the Pierre Boulez Saal since its inception.

November 2023

Jens Harzer

Recitation

Born in Wiesbaden in 1972, Jens Harzer studied acting at the Otto Falckenberg School in Munich. From 1993 he was a member of director Dieter Dorn’s ensemble for 16 years, first at the Munich Kammerspiele, then at the Bavarian State Theater. He also made guest appearances at theaters such as Berlin’s Schaubühne and Deutsches Theater, Hamburg’s Deutsches Schauspielhaus, the Frankfurt Schauspiel, the Salzburg Festival, and the Vienna Burgtheater. collaborating with Peter Zadek, Andrea Breth, Herbert Achternbusch, Luc Bondy, and Jürgen Gosch, among others. In 2009, he joined the ensemble of Hamburg’s Thalia Theater, where he has worked with directors including Dimiter Gotscheff, Luk Perceval, and Leander Haußmann. Since 2015, he has collaborated closely with Johan Simons at the Bochum Schauspielhaus, where he has also been on the roster since 2018. On screen, he has worked with Michael Verhoeven, Hans-Christian Schmid, Bülent Akıncı, and most recently Tom Tykwer, Wim Wenders, and Hermine Huntgeburth. In addition to numerous national and international awards, Jens Harzer has been the bearer of the Iffland Ring since 2019, an honor traditionally bequeathed to the “most significant actor of German-speaking theater” by the previous bearer.

November 2023