Michele Pasotti Musical Direction and Lute

Alena Dantcheva Soprano

Giovanna Baviera Soprano and Viola da gamba

Bernd Froelich Altus

Massimo Altieri, Gianluca Ferrarini, Roberto Rilievi Tenor

Mauro Borgioni Bass

Enrico Onofri Violin

Teodoro Baù Viola da gamba

Giulia Genini Dulcian

Margret Koell Harp

Federica Bianchi Harpsichord and Organ

Program

Ancor che col partire

Settings and Adaptations by de Rore, Dalla Casa, Onofri, Gabrieli, de Monte, Rognoni, Bovicelli, Striggio, Vecchi, Pasquini, Bassano, del Liuto, and Lasso

Cipriano de Rore (c. 1515–1565)

Ancor che col partire

from Primo libro di madrigali à quattro voci di Perissone Cambio con alcuni di Cipriano Rore (1547)

Girolamo Dalla Casa (?–1601)

Ancor che col partire

from Il vero modo di diminuir con tutte le sorti di stromenti & di voce humana (1584)

Enrico Onofri (*1967)

Fantazia upon Ancor che col partire (instrumental)

World Premiere

Andrea Gabrieli (1532/33–1585)

Ricercar „Ancor che col partire“ (instrumental)

from Il terzo libro de ricercari tabulati per ogni sorte di stromenti da tasti (1596)

Philippe de Monte (1521–1603)

Gloria

from the Missa "Ancor che col partire"

Giovanni Battista Bovicelli (fl. 1592–94)

Angelus ad pastores

from Regole, passaggi di musica, madrigali, e motetti passeggiati (1594)

Giovanni Bassano (1551/52–1617)

Ancor che col partire (instrumental)

from Motetti, madrigali et canzoni francese (1591)

Alessandro Striggio (c. 1536/37–1592)

Ancor ch’io possa dire

from Primo libro de madrigali à sei voci (1560)

Riccardo Rognoni (c. 1550–before 1620)

Ancor che col partire per la viola bastarda (instrumental)

from Il vero modo di diminuire con tutte le sorte di stromenti & anco per la voce humana (1592)

Orazio Vecchi (1550–1605)

Ancor ch’al parturire

from L’Amfiparnaso (1597)

Ercole Pasquini (?–1608/18)

Ancor che col partire (instrumental)

Giovanni Bassano

Ancor che col partire per sonar più parti

from Motetti, madrigali et canzoni francese

Andrea Gabrieli

Ancor che col partire

from Primo libro delle iustiniane à tre voci (1570)

Lorenzino Tracetti detto del Liuto (c. 1553/55–1590)

Ancor che col partire (instrumental)

from Thesaurus harmonicus (1603)

Giovanni Battista Bovicelli

Ancor che col partire

from Regole, passaggi di musica, madrigali, e motetti passeggiati

Orlando di Lasso (1532–1594)

Magnificat "Ancor che col partire" LV 557 (1576)

Riccardo Rognoni

Ancor che col partire per sonar con ogni sorti di stromento (instrumental)

from Il vero modo di diminuire

Cipriano de Rore

Ancor che col partire

Without intermission

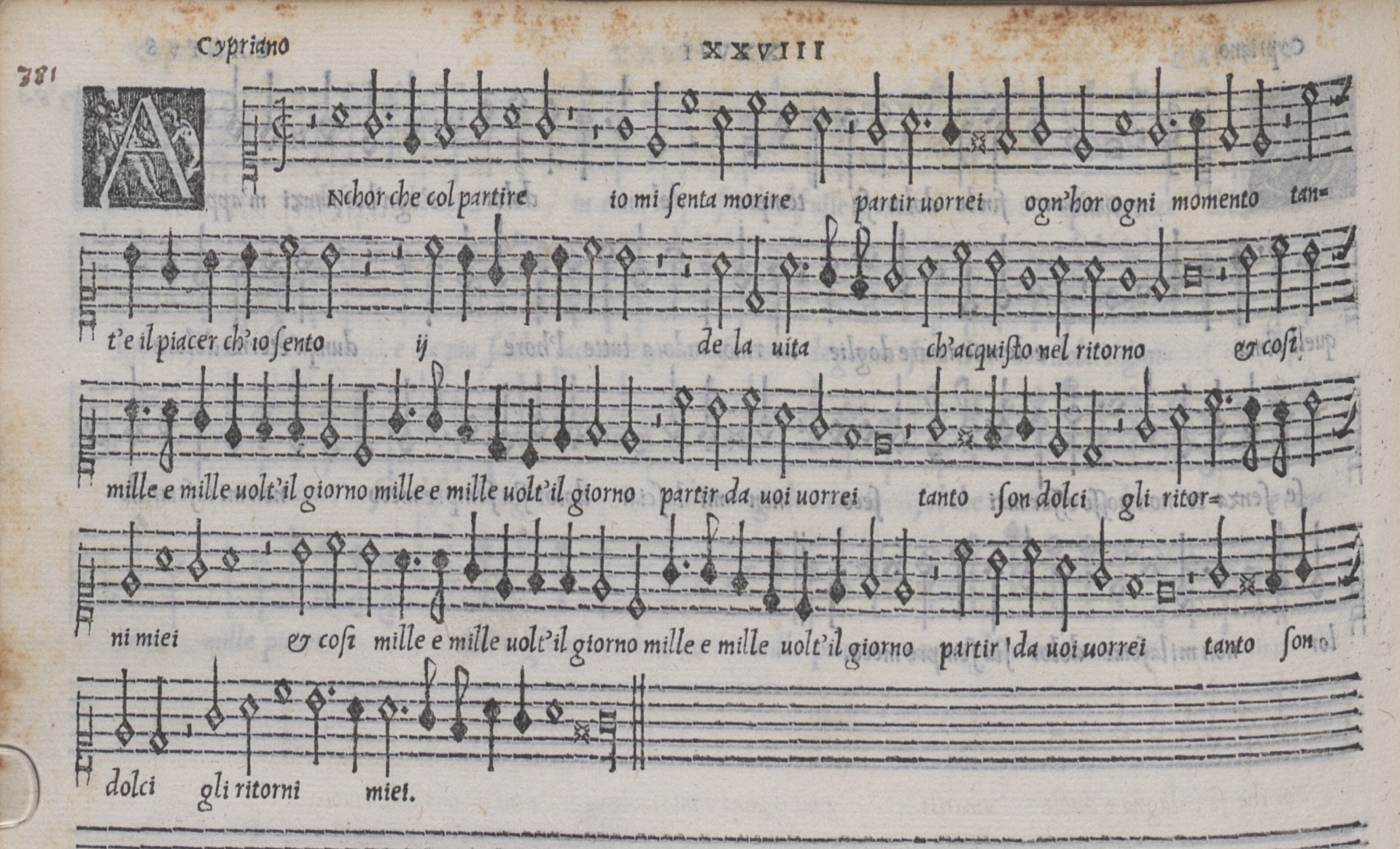

The first edition of Cipriano de Rore's Ancor che col partire, Venice 1547 (Bavarian State Library, Munich)

Leaving, Loving, Dying

Cipriano de Rore’s Ancor che col partire is the most successful madrigal of all time. It was copied, diminished, parodied, and fascinated generations of composers. With this program, we aim to reignite that hypnotic power, to cast that spell on our audience (and on ourselves) by presenting a concert made entirely of Ancor che col partire and its infinite variations.

Essay by Michele Pasotti

Leaving, Loving, Dying

The Metamorphosis of a Madrigal

Michele Pasotti

Cipriano de Rore’s Ancor che col partire is the most successful madrigal of all time. It was copied, diminished, parodied, and taken as a model for masses, Magnificats, and instrumental pieces. Its melodies fascinated generations of composers such as Lassus, Gabrieli, Vecchi, Cabezón, Rognoni, Pasquini, Dalla Casa, Striggio, Galilei, Bassano, Jasquet of Mantua, Bovicelli, and Terzi—the list goes on. It became the idea of the madrigal, its archetype.

Its text speaks of love, leave-taking, and death: a clear erotic allegory. The manner of its setting, the melancholy permeating its mode and lines, however, lend it a unique charm, defying definitions and formulas.

With this program, we aim to reignite that hypnotic power, to cast that spell on our audience (and on ourselves) by presenting a concert made entirely of Ancor che col partire and its infinite variations. It is conceived as a single uninterrupted piece, a suite without breaks in which the madrigal transforms into vocal and instrumental diminutions, parodies, a Magnificat, and a Gloria. It is a radical quest for this particular enchantment.

Cipriano de Rore was born in Ronse (now Renaix, in Flanders) in 1515 or 1516. His musical career developed in Italy, as it did for many other Flemish masters, where he was simply referred to as Cipriano or sometimes “il divino Cipriano.” Over the course of his life, his style, particularly in Italian madrigals, underwent significant changes toward a dramatization of the text, which eventually led to Monteverdi’s claim that Cipriano was the founder of the Seconda pratica, the “second practice” or new style of the early 17th century. (Monteverdi’s teacher Marc’Antonio Ingegneri was a student of Cipriano.) Probably traveling to Italy at a young age, Cipriano may have been in the service of Margaret of Parma, the illegitimate daughter of Charles V. Some sources refer to him as a student of Adrian Willaert, the great Flemish master, at the time maestro di cappella at San Marco in Venice. After living in Brescia and visiting Venice, Cipriano was appointed maestro di cappella at the Este court in Ferrara in 1546. The city had been a leading musical center since the second half of the 15th century. He was 30 years old at the time and remained in Ferrara until 1558, a few years before his death in 1565.

Cipriano’s Ferrara years were very productive. Ancor che col partire belongs to the first phase of his madrigal writing, with a setting for four voices (five voices would later become more common for him), generous use of imitation (he subsequently preferred much more homophonic structures), and a clear modal structure. The piece was first published in 1547 by Gardano in Venice as part of Perissone Cambio’s Primo libro di madrigali à quattro voci di Perissone Cambio con alcuni di Cipriano Rore.

The poem, by an anonymous author, on the first level can be read as the description of a parting between two lovers and the joys of their reunions. But since “partire” (leaving), “ritorno” (returns), and “morire” (dying) are well-known topoi of erotic poetry, Ancor che col partire essentially paints a sex scene. As the musicologist Christopher Reynolds writes: “The lover pivots from a description of pain and pleasure at the beginning to express his or her resolve to endlessly repeat the cycle of departure and return ‘each hour,’ ‘each moment,’ and finally ‘a thousand, thousand times a day.’”

Musically the madrigal is built on the imitation and repetition of the first motive, binding returns in music and text together. Through the systematic use of weak cadences and suspensions, Cipriano achieves an effect of a never-ending quest until the end of the madrigal, echoing the never-ending desire between the lovers. The erotic matter is by no means treated in a “popular” musical language (as Vecchi and Gabrieli would do later). On the contrary: a bittersweet melancholy, proper to the mode in which the madrigal is written, pervades the entire composition and corresponds very well with the unfulfilled desire of the attenuated cadences. The words “Tant’è il piacer ch’io sento” (Such is the pleasure that I feel) are set in shorter note values, which intensify even more at “et così mille, mille volte il giorno” (And so thousands and thousands of times a day), where a dotted rhythm appears and lends energy to the enthusiastic phrase. The final section, starting with these words and ending with “Tanto son dolci gli ritorni miei” (So sweet are my returns), is repeated twice, with a stronger cadence at the very end—which adds to the impression of “an endless loop of departures and returns” (Reynolds).

Any attempt to grasp in words Ancor che col partire’s enchantment and hypnotic power is probably in vain, and any impressions one might have are much more easily heard than described. The work’s effect on Cipriano’s contemporaries was prodigious. We feel the same.

Ancor che col partire soon became a favorite subject for diminution—a compositional technique in which the note values of a given melodic line are shortened or the melody is embellished with ornamentation. Between 1584 and 1624, composers including Girolamo Dalla Casa, Jacopo Bassano, Riccardo Rognoni, Giovanni Battista Bovicelli, Francesco Rognoni, and Giovanni Battista Spadi wrote some of the most important of these adaptations, all providing their version of Ancor che col partire (and in many cases more than one).

We will perform several of these, beginning with the one by Girolamo Dalla Casa, published in 1584 in his Il vero modo di diminuir con tutte le sorte di strumenti di fiato & di corda & di voce humana (The True Method of Diminution with All Kinds of Wind and String Instruments and the Human Voice). Since 1568, Dalla Casa with his two brothers had formed the first permanent instrumental ensemble at San Marco in Venice. By the 1580s, the group had expanded, and he was appointed “capo de’ concerti.” The diminution of Ancor che col partire that we will perform is taken from the section “Madrigali da cantar in compagnia, & anco co’l Liuto solo” and will be accompanied by a lute.

I am very pleased that Enrico Onofri is joining us for tonight’s concert. He is an expert on the 16th and 17th-century world of diminutions, which is why I asked him to write a new diminution on Ancor che col partire. In doing so, he took inspiration from the 17th-century English divisions, creating a beautiful two-part fantasia that is halfway between an English division and a fantasia in the style of Matthew Locke. It receives its world premiere this evening.

Another type of imitative composition is known as a ricercar. The term originally referred to prelude-like pieces for lute or keyboard instruments and through the Renaissance evolved into its later meaning. At the end of the 16th century, Andrea Gabrieli, organist at San Marco and a colleague of Dalla Casa and Bassano, published four volumes of ricercars in which he frequently uses inversion, augmentation, diminution and other fugal techniques. One of these is the ricercar Ancor che col partire, performed here on the double harp.

Cipriano’s madrigal inspired not only diminutions and instrumental renditions but also sacred music. Flemish master Philippe de Monte was the most prolific madrigal composer of his time, yet here we present the Gloria from his Missa "Ancor che col partire". It belongs to the genre of parody masses, written using musical material from a preexisting chanson, madrigal, or motet—which is fully recognizable in this beautiful piece.

Giovanni Battista Bovicelli was an authority on the creation of vocal diminutions. His Angelus ad pastores, taken from Regole, passaggi di musica, madrigali et motetti passeggiati is a virtuoso adaptation of Ancor che col partire, but it is also an example of what is known as contrafactum, the replacement of an existing text with a new one. Since Bovicelli’s work is a piece of sacred music, the subject matter here is not exactly the same…

The next piece by Giovanni Bassano spotlights the dulcian (already called fagotto in late-Renaissance Italy). Giovanni came from a famous dynasty of musicians from Bassano del Grappa who were active in Venice and England. Their association with music for wind instruments in Venice goes back to the “Piffari del Doge” at the beginning of the 16th century. Giovanni Bassano succeeded Girolamo Dalla Casa as “capo de’ concerti” at San Marco. His instrumental diminution is taken from Motetti, madrigali et canzoni francese, published in 1591.

Ancor ch’io possa dire by Alessandro Striggio, a virtuoso performer and leading composer of madrigals and stage music of his time, is a very peculiar composition that can be defined as a risposta, or “response,” to Ancor che col partire. Christopher Reynolds, who examined the relationship between Striggio’s madrigal and its model, writes: “[The practice] of answering a poem or madrigal based on that poem—a proposta—with an answering poem and madrigal—a risposta—resulted in many pairs of songs that drew on related musical elements while establishing some degree of contrast, such as in the contrast between the separate voices of two lovers. […] But it was also possible for a composer to reply to another composer’s madrigal by setting a poem that had itself been written as a reply to the poem of the earlier madrigal.” In this case, Striggio set a text by Girolamo Parabosco, published in 1547. His composition, Reynolds writes, “was as much a response to De Rore’s music as Parabosco’s verses had been to the earlier anonymous poem. […] Parabosco’s protagonist is a lover whose views diametrically oppose those of the individual who animates De Rore’s madrigal. Striggio does his best to support Parabosco’s contradictory risposta with music that is every bit as oppositional. Phrase by phrase he inverts the motives of Ancor che col partire and also De Rore’s deployment of cadences.”

If there is one musician who was completely caught in the enchantment of Ancor che col partire, it was Riccardo Rognoni. In his 1592 Il vero modo di diminuire con tutte le sorte di stromenti, he provides eight examples of diminutions—half of them are of Ancor che col partire. The one heard tonight is designated “per la viola bastarda,” a type of viola da gamba particularly suited for a style of diminution that is not confined to a single voice but runs through different voices and registers. (The word bastarda is here used in the sense of something “mixed.”)

In addition to diminutions, sacred pieces, contrafacta, and instrumental renditions, there were also parodies—a piece that inspired those bore the ultimate seal of success. The music of Orazio Vecchi was known for its satiric vein, popular appeal, and rhythmic vitality, and L’Amfiparnaso, his most famous work, contains Ancor ch’al parturire, a parody of Ancor che col partire. The humorous text twists the sense of the original poem from the erotic context to the pleasures of drinking and eating, which are evoked in comic language. Cipriano’s music, though transformed, is recognizably present, with a fifth voice added.

Organ and harpsichord account for a large number of Ancor che col partire arrangements. Ercole Pasquini was a leading organ player in Ferrara and Rome and a predecessor of Frescobaldi. His instrumental rendition of Cipriano’s madrigal is a triumph of virtuosity, showcasing most of the ornamentations known to the keyboard.

The instrumental approach of diminuire alla bastarda has already been mentioned, but this style was also practiced by singers, especially in the bass voice. This is the case in Bassano’s second diminution on Ancor che col partire. It is labelled “per sonar a più parti,” which indicates that, although the music gravitates toward the bass part, it frequently includes flourishes of tenor or even alto phrases. Bassano’s Motetti, madrigali et canzoni francese is the main source for alla bastarda singing and playing in the 16th century. This diminution, like Rognoni’s for viola bastarda, explores the meraviglia, the “wonder” of a voice—or instrument—venturing into extreme registers.

In the second half of the 16th century, giustiniane were the Venetian answer to the Neapolitan villanelle: simple polyphonic pieces mimicking popular songs, themes, and language. Often, as in Andrea Gabrieli’s composition, a comic effect is achieved by means of repetitions that imitate stuttering and very explicit, even obscene language. This parody is close to the original poem in structure but twists the vocabulary toward a low, vulgar register.

As one of the main instruments of the 16th century, the lute is often found in renditions of Ancor che col partire. Tonight we present Lorenzino del Liuto’s intavolatura, taken from Jean-Baptiste Besard’s Thesaurus Harmonicus. Probably born Lorenzino Tracetti and known as Lorenzino del Liuto, he was the son of a Flemish musician and an internationally renowned lute virtuoso active mostly in Rome. His version of Ancor che col partire is one of the finest pieces of the late–16th century repertoire.

It was not unusual for Renaissance musicians to sing and play at the same time. But those who were able to do so at a high level of virtuosity were few and celebrated accordingly—as they are today. This evening, La fonte musica member Giovanna Baviera will perform a vocal diminution of Ancor che col partire from Bovicelli’s Regole, passaggi di musica, madrigali et motetti passeggiati—singing the cantus part and playing a reduction of the other voices on the viola da gamba.

The third piece of sacred music on tonight’s program is a work by the great Orlando di Lasso. Seduced by the beauty of Ancor che col partire, he wrote a wonderful Magnificat in which plain chant and five-part polyphony alternate which quotes and reworkings of Cipriano’s madrigal.

The last diminution you will hear is once again by Riccardo Rognoni, but it is meant “per sonar con ogni sorte di stromento”—to be played on any kind of instrument. It diminishes the top line, so should ideally be performed on a cantus instrument. Violin, cornet, or flute are the best candidates, but a violin seems to fit it particularly well, as Rognoni was not only a master on the treble viol but also the first to write about the “violino da brazzo,” the forerunner of the modern violin.

Our program ends as it began—with Cipriano de Rore’s original madrigal, the objective of the quest and the inspiration for these musical metamorphoses.

Cipriano de Rore, miniature by Hans Mielich (from a manuscript copy of Rore's motets dedicated to Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria, 1559) (Bavarian State Library, Munich)

The Ensemble

La fonte musica

The Italian ensemble La fonte musica brings together some of the most renowned musicians from the European Early Music scene under the direction of its founder Michele Pasotti. The group specializes in European music from the 14th to the 17th centuries, based on many years of experience with this repertoire as well as a detailed study of the surviving sources and the culture of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance in general. La fonte musica has appeared at some of the most renowned Early Music festival across Europe, including Oude Muziek Utrecht, the Ravenna Festival, the Innsbruck Festival for Early Music, Laus Polyphoniae in Antwerp, Urbino Musica Antica, and the Brighton Early Music Festival. This season, the ensemble has presented Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo at the Vienna Konzerthaus, Antwerp’s De Singel, Concertgebouw Cruges, and at Teatro Fraschini in Pavia. La fonte musica has released several highly acclaimed recordings, including a complete edition of the works of Antonio Zacara da Teramo, which won the Diapason d’or and the German Record Critics’ Award. The group has also been honored with the 2023 Premio Abbiati as ensemble of the year and has been a regular guest at the Pierre Boulez Saal since 2020.

May 2025