Nils Mönkemeyer Viola

William Youn Piano

Program

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Sonata for Violin and Piano in G major K. 379 (373a) (1781)

Arrangement for Viola and Piano

I. Adagio –

II. Allegro

III. Thema. Andantino cantabile –

Var. I–V – Thema. Allegretto – Coda

Andante and Allegretto in C major K. 404 (c. 1782)

Allegro in B-flat major K. 372 (1781)

[Without tempo indication] in C minor K. 396 (c. 1782)

Fragments with Interstitial Moments by Isabel Mundry (*1963)

Intermission

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Sonata Movement in F-sharp minor D 571 (1817)

Fragment completed by William Youn

Allegro moderato

Sonata for Arpeggione (Viola) and Piano in A minor D 821 (1824)

I. Allegro moderato

II. Adagio –

III. Allegretto

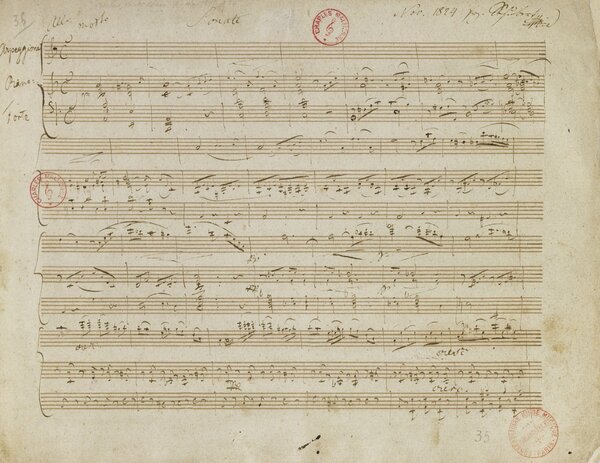

Schubert’s “Arpeggione” Sonata in the composer’s manuscript (© Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Imaginative Spaces

A musical composition does not necessarily have to be complete to exert a fascination on us. Sometimes even the unfinished is perfect, fragments make powerful statements, and daring experiments are revealed within a few measures. The fragmentary has a disquieting element; the openness of the unfinished, however, also offers space for imagination. This is the territory Nils Mönkemeyer and William Youn step into together with composer Isabel Mundry—exploring mysterious blank spaces and unheard-of elements in fragments by Mozart and Schubert.

Program Note by Anne do Paço

Imaginative Spaces

Finished and Unfinished Works by Mozart, Schubert, and Mundry

Anne do Paço

A musical composition does not necessarily have to be complete to exert a fascination on us. Sometimes even the unfinished is perfect, fragments make powerful statements, and daring experiments are revealed within a few measures. The reasons for leaving a work incomplete may be manyfold—ranging from artistic or financial failure, a simple lack of time, illness or death to an aesthetic that declares the fragment a viable artistic form. The fragmentary has a disquieting element; the openness of the unfinished, however, also offers space for imagination. This is the territory Nils Mönkemeyer and William Youn step into together with composer Isabel Mundry—exploring mysterious blank spaces and unheard-of elements in fragments by Mozart and Schubert. At the same time, Mönkemeyer takes on a variety of roles with his viola, performing a violin sonata by Mozart and the sonata Schubert originally intended for an arpeggione on his own instrument.

“The only ones of their kind”

Mozart’s Sonata in G major K. 279 is part of the collection of “Six Sonates” that Carl Friedrich Cramer’s Magazin der Musik called “the only ones of their kind” on April 4, 1783: “Rich in new ideas and traces of the great musical genius of their author. Very brilliant, and appropriate to their instrument,” the “violin linked so artfully to the piano part that these sonatas require a violinist of equal capability as the pianist.” The piece, like the Allegro in B-flat major K. 372 that remained a fragment, was written for the violinist Antonio Brunetti in the spring of 1781, in the context of the Salzburg court’s visit to Vienna, during which Mozart permitted himself a series of professional transgressions that culminated in his infamous firing from the staff of Prince-Archbishop Colloredo in June of the same year: despite a strict proscription of outside work, he gave a concert with Vienna’s Tonkünstlersozietät (Society of Musical Artists), while also ignoring the rules prohibiting him from lodging privately with the family of Constanze Weber, who would subsequently become his wife.

Mozart’s sonatas and sonata fragments of this period reflect his mature artistic self-confidence. With its unusual dimensions, the opening Adagio of the G-major Sonata is more than a mere slow introduction: it is a movement in its own right, including an exposition repeat that, however, breaks off where traditionally a reprise would follow. Its character, marked by arpeggios and rich ornamentation, combined with an instable meter, also points to a fantasy rather than a sonata. This is followed by an expressive Allegro in G-minor, propelled forward by sighing figures, its development reduced to a mere ten measures, while the reprise is expanded to form a turbulent finale.

The second movement consists of five variations on a lyric theme that, with its descending seconds, is reminiscent of a passacaglia ostinato. Mozart not only translates this theme into different musical atmospheres, he also illuminates the encounter between the two instruments from different angles: as an equal duo, with a piano solo in the first variation, and a cameo of the violin as a guitar or lute in the gentle pizzicato of the fifth variation—a serenade that suddenly plunges into dark drama. Ornaments, fast runs, and daring leaps characterize this technically challenging movement that ends with a reprise of the theme in a faster allegro tempo.

On April 8, 1781, Mozart reported to his father Leopold that he had composed the sonata “last night between 11 and 12.” We do not know whether its unusual structure was due to excessive time pressure or a conscious plan. In any case, this is one of Mozart’s outstanding violin sonatas. Thanks to its rather low tessitura, it is also particularly suitable for performance on the viola.

Gestures of Friendship

When Georg Nikolaus Nissen, who would go on to become Mozart’s biographer (as well as Constanze’s second husband), joined Abbé Maximilian Stadler in surveying the composer’s estate, the two discovered a wealth of fragments, permitting astonishing insights into Mozart’s workshop. Among these were eight unfinished works for violin and piano. Several of them had reached such advanced stages that Stadler completed and published them—not without ulterior economic motives. This practice was less interesting to William Youn and Nils Mönkemeyer than pursuing an idea they developed together with Isabel Mundry in preparation for the 2022 Mozartfest in Würzburg, namely to delve into the lacunae of the three fragments K. 404, 396, and 372 from a vantage point of historical distance.

This resulted in Zwischenmomente, or “interstitial moments,” that Mundry does not consider independent compositions, but rather gestures of friendship, a playful offshoot of a collaboration that usually pursues quite different dimensions, as witnessed by her Viola Concerto written for Mönkemeyer and a large-scale piece she is working on for Youn. At the same time, however, on a smaller scale, the pieces reflect the issues currently on the Munich-based composer’s mind: “In the classical sense, composing means having an inner idea of the sounds. I, on the other hand, have been interested for several years in composing with regard to the question of listening. What kind of space do the sounds inhabit, how does listening articulate itself in musical structure? I don’t show what I want to express, but rather, what ‘impresses’ itself upon me,”—in the case of the interstitial moments, “a trace that Mozart’s music leaves in my own hearing, but also sounds that my ears anticipate.”

Nothing is known about the genesis of Mozart’s Andante and Allegretto K. 404. Both two-part movements, of equally insouciant, suite-like character, were first published in 1803–4 as a Sonatina for Violin and Piano. Whether they actually belong together or whether something might be missing we don not know. A piece that clearly remained a fragment is the Allegro K. 372, which belongs to the environs of the G-major Sonata and has come down to us only up to the end of the exposition. Mozart had already dated the autograph and given it the title “Sonata I.” Musicologists usually explain the fact that he left it unfinished after 65 measures with similarities with the Sonata K. 378, which was included in the “Six Sonates” alongside the G-major work.

One of Mozart’s most mysterious works is the fragment K. 396. With Stadler’s completions, it became known as a Fantasy for Piano. Mozart himself only wrote the first 27 measures, and they seem to fly in the face of all genre rules. The beginning is characterized by powerful, expansive arpeggios covering several registers, reminiscent of Bach. This music starts a prelude to a fugue, but no sooner has this registered than the atmosphere swings towards intimacy and pensiveness, only to be followed quite unexpectedly by another theme of a sanguine, determined character—contrasting worlds quite alien to the form of the prelude. Was it this freedom that persuaded Mozart to abandon the composition and make a second attempt with a version that adds a solo violin to the piano part? That violin part, however, is only notated for the last five measures. Obviously, Mozart also abandoned that attempt.

“How far do these Mozart worlds turn into an echo, an inkling, how can I move towards these sounds and then away from them again?”, Isabel Mundry asked herself as she began to take the measure of the open spaces of the fragments, using the means of proximity and distance: “I blur Mozart’s harmonies, and I return things to them, I slip sound elements between them, from which Mozart ultimately is filtered out again. To me, it’s about balancing between Mozart’s works, and I only move away from them at the end, with a piece for solo viola dedicated to Nils.”

Paths of One’s Own

To Franz Schubert, Mozart was one of the great role models: “Oh Mozart, immortal Mozart, how many, how infinitely many such beneficial stamps of a brighter, better life have you imprinted on our souls!”, the 19-year-old Schubert wrote in his diary in June 1816. A little while later, he began seeking out a path of his own in dealing with the sonata form, as numerous sketches demonstrate, including the Sonata Movement D. 571. In July 1817, Schubert had begun this work in the unusual key of F-sharp minor, entitling it “Sonata V” even in the autograph. With its completely new qualities of sound and expressiveness, it no longer conforms to traditional models. Measured against the dialectic principle of thematic development, the movement must be judged a failure—as the manifestation of a composer’s search for his very own path, it is unprecedented. Schubert is not out to reach a goal here, not to consciously shape a musical architecture; what he is seeking is a circular movement in which he seems to be listening to himself. Through ever-new ways of illuminating material that may be described less in terms of thematic qualities and more of unfolding harmonic force fields, he opens up multiple new sonic spaces. After 141 measures, however, the composition breaks off, at the end of the passage one might call the development section. The practice of not writing out a reprise, which is a repetition of the exposition, is one occasionally found in Schubert’s manuscripts. Accordingly, William Youn has added such a repetition to the fragment, requiring only a few additional measures to serve as a transition and coda.

Schubert composed one of his most beautiful sonatas for an instrument that has been forgotten today: the arpeggione, known alternatively as “guitar d’amour,” “bowed guitar,” or “guitar violoncello,” and invented by the Viennese luthier Johann Georg Staufer in 1823. The arpeggione is a combination of the guitar, from which its fingerboard with its metal frets and the tuning of its six strings to E-A-d-g-b-e’ are derived, and the cello, with which the arpeggione shares not only the upright positioning between the player’s knees, but also the rounded bridge, which enables the strings to be played with a bow. The instrument did not bring its inventor lasting success, and it would presumably have fallen entirely into oblivion, had it not inspired Schubert to compose his so-called “Arpeggione” Sonata in November 1824. Written for the guitarist Vinzenz Schuster, the work has found a permanent place in the repertoire for viola or cello and piano—even if performances on a four-stringed instrument do require adaptations to the arpeggios and double stops conceived for the fingering technique of the arpeggione.

The piano begins the first movement with a theme of yearning nostalgia. After a dramatic transition, this is followed by a dance-like, virtuosic second theme that throughout the development vainly attempts to gain the upper hand over the melancholy atmosphere. The Adagio is a songful elegy—yet even the beauty of this world is endangered. Gradually, Schubert drains the élan vital from his music, only to revive this vivacious impulse shortly before it flickers out entirely, finding an outlet in a final Allegretto. Conceived as a rondo, this movement displays not only abundant melodic invention but also a virtuosity that is unusual for Schubert and was presumably inspired by the technical possibilities the arpeggione offered.

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

Anne do Paço studied musicology, art history, and German literature in Berlin. After holding positions at the Mainz State Theater and the Deutsche Oper am Rhein, she has been chief dramaturg at the Vienna State Ballet since September 2020. She has published essays on the history of music and dance of the 19th to 21st centuries and has written program notes for Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, the Vienna Konzerthaus, and the Opéra National de Paris, among others.

The Artists

Nils Mönkemeyer

Viola

Nils Mönkemeyer studied with Hariolf Schlichtig at the Munich Musikhochschule, where he has held a professorship himself since 2011. He also taught at Dresden’s Hochschule für Musik Carl Maria von Weber and at the Escuela Superior de Música in Madrid. He regularly collaborates with conductors such as Andrey Boreyko, Sylvain Cambreling, Kent Nagano, Mark Minkowski, Vladimir Jurowski, Michael Sanderling, Joana Mallwitz, and Simone Young and appears as a soloist with Zurich’s Tonhalle Orchestra, the London Philharmonic, the Helsinki Philharmonic, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Berlin’s Radio Symphony and Konzerthaus Orchestras, Leipzig’s MDR Symphony, and the Staatskapelle Weimar, among others. An acclaimed chamber musician, he is a member of the Julia Fischer Quartett and performs as a trio with Sabine Meyer and William Youn, who has also been his longtime duo partner. This current season, Nils Mönkemeyer appears at Wigmore Hall in London, the Vienna Musikverein, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, Munich’s Prinzregententheater, Alte Oper Frankfurt, the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Festival, and the Mozartfest Würzburg. Together with clarinetist Andreas Ottensamer and double bassist Edicson Ruiz, he premieres Vladimir Tarnopolski’s Im Dunkel vor der Dämmerung with the Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra conducted by Kent Nagano.

January 2024

William Youn

Piano

William Youn began his musical education in Korea, moved to the U.S. at a teenager, and later studied at the Hanover Musikhochschule and at the International Piano Academy Lake Como in Italy, where his teachers included Karl-Heinz Kämmerling, Dmitri Bashkirov, Andreas Staier, and Menahem Pressler. Now based in Munich, he performs with orchestras such as the Munich Philharmonic, Berlin’s Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester, Münchner Kammerorchester, Cleveland Orchestra, and the Orchestra of St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater. He has enjoyed a close collaboration with Nils Mönkemeyer for many years, and together the two artists have performed countless concerts and recorded several acclaimed CDs. His chamber music partners also include Sabine Meyer, Julian Steckel, Carolin Widmann, Veronika Eberle, and the Aris Quartett, with whom he appears at major festivals across Europe. Recently William Youn has also made a name for himself performing on the fortepiano. His debut solo album featuring works by Robert and Clara Schumann, Schubert, Liszt, and Zemlinsky was released in 2018 and followed by his acclaimed complete recording of Franz Schubert’s piano sonatas, which he completed in 2022. This month saw the release of his first orchestral recording of piano concertos by Reynaldo Hahn and Nadia Boulanger, on the occasion of Hahn’s 150th birthday.

January 2024