Laurence Dreyfus Treble Viol and Musical Direction

Emilia Benjamin Treble Viol

Jonathan Manson Tenor Viol

Heidi Gröger Tenor Viol

Markku Luolajan-Mikkola Bass Viol

Program

Christopher Tye

Selected In nomines

O lux beata trinitas

Sit Fast

Matthew Locke

Suite No. 5 in G minor from Consort of Four Parts

William Lawes

Consort Sett à 5 in A minor

Consort Sett à 5 in F major

Henry Purcell

Selected four-voice Fantasies

Christopher Tye (c. 1505–1572/73?)

In nomine "Believe me"

In nomine "Round"

In nomine "Weep No More, Rachel"

In nomine "Say so"

O lux beata trinitas

Matthew Locke (c. 1622–1677)

Suite No. 5 in G minor from Consort of Four Parts

I. Fantazie

II. Courante

III. Ayre

IV. Saraband

William Lawes (1602–1645)

Consort Sett à 5 in A minor

I. Fantazy

II. Fantazy

III. Aire

Henry Purcell (1659–1695)

Fantasia à 4 in A minor Z 740

Fantasia à 4 in D minor Z 743

Fantasia à 4 in G minor Z 735

Intermission

Christopher Tye

Sit Fast

Henry Purcell

Fantasia à 4 in F major Z 737

Fantasia à 3 in F major Z 733

Fantasia à 4 in B-flat major Z 736

William Lawes

Consort Sett à 5 in F major

I. Fantazy

II. Paven

III. Aire

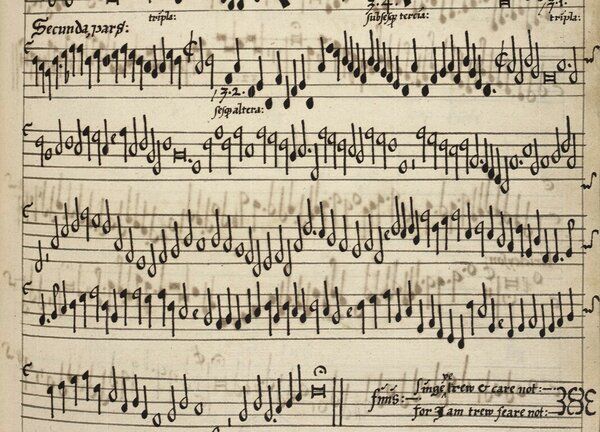

Christopher Tye’s Sit Fast in the Baldwin Commonplace Book (c. 1580–1606) with the composer’s inscription at bottom right: “Singe ye trew & care not, for I am trew feare not.”

Flights of Fancy

The tradition of English consort music from the 16th and 17th centuries exhibits some of the most accomplished chamber music composed before the first Viennese school. Freed from the institutional constraints of vocal music composers indulged in forms of expression and experimentation unmatched by any other instrumental repertoire on the European continent. Our program is devoted to the boldest and the most eccentric of them.

Essay by Laurence Dreyfus

Flights of Fancy

Music for Viol Consort by Tye, Locke, Lawes, and Purcell

Laurence Dreyfus

The tradition of English consort music from the 16th and 17th centuries exhibits some of the most accomplished chamber music composed before the first Viennese school of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Freed from the institutional constraints of vocal music—which was almost exclusively bound to religious contexts and conventions—composers indulged in forms of expression and experimentation unmatched by any other instrumental repertoire on the European continent. Our program is devoted to the boldest and the most eccentric of the English consort composers, whose works continue to delight audiences today with their fresh approach to musical technique and affect.

The curious and complex music of Christopher Tye propels us into a private world of astounding imagination. A leading composer of sacred music under four English monarchs, Tye gives free rein to his most unbridled fantasy in his surviving instrumental works. Throughout this corpus, and especially in the 23 In nomines probably composed in the 1550s—he wrote more pieces of this genre than any other composer—one comes to expect jagged lines, indecorous clashes, and sudden deviations that work their special magic, veering between lyrical contemplation and jubilant rapture. In one astonishing anecdote—though only reported after his death—the antiquarian Anthony Wood recounts: “Dr Tye was a peevish and humoursome man, especially in his latter dayes, and sometimes playing on the organ in the chapel of Queen Elizabeth which contained much musick but little delight to the ear, she would send the verger to tell him that he play’d out of tune: whereupon he sent word that her eares were out of Tune.”

In his series of In nomines, Tye sets about investigating the nature of an instrumental piece based on a plain four-voiced passage in the Benedictus of John Taverner’s Mass “Gloria tibi Trinitas” set to the words “In nomine.” And in all these pieces Tye seems implicitly to pose the questions: in what ways can a piece of music be explicitly instrumental rather than vocal? How far can one pursue metric experiments without a conductor beating time so that players may play from their individual parts (without a score) and still combine into a harmonious whole? Some titles of Tye’s In nomines even seem to indicate some sort of anxiety about the music’s probity: Follow Me, Beleve Me, Saye So, Howld Fast, Seldom Sene. The remarkable three-voice Sit Fast, a “free” composition, ends with a striking inscription: “Sing ye trew & care not, for I am trew, feare not.” Speaking in the first person, the piece reassures an anxious performer not to be frightened by its convoluted rhythms and unseemly counterpoint: they will make sense in the end if you avoid worry and fear. At his most demanding, Tye has players compute 9 against 2 and 4 simultaneously, and only at the end does he provide a joyful escape from the rhythmic labyrinth.

Matthew Locke, a fascinating and cantankerous character known for his argumentative writings, shows his flair for breaking rules and undoing conventions in his Flat Consorts, both written in keys with flats in the signature. By the time of the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, Locke was England's leading composer. He was appointed composer to the King’s Private Music, the pool of musicians that played in the royal apartments and continued the tradition of consort music developed earlier. However, by that time he had to put up with King’s “utter detestation of Fancys,” his dislike of the old fantasy tradition and his preference for French-style dance music. We know that Locke had little time for French dance music, except for some French Courantes that he anglicized in his own peculiar way. His constant fits and starts, along with drawn-out appendages to the stylized dances as a kind of grave apotheosis, mark a new turn in the English tradition that would strongly influence Henry Purcell’s Fantasies of 1680.

With these youthful viol works, composed over the course of one summer in the year 1680, Henry Purcell adds what was to be the final and most brilliant chapter in the history of the English viol “fantazia,” as Purcell spelled it in his autograph. These are works that find the 20-year-old Purcell composing in a contemplative idiom that many would think better suited to an old man, i.e., turning to the most severe forms of imitative and invertible counterpoint as a highly speculative and experimental field for musical exploration. Purcell makes clear his awareness of past masters of the Fantasy tradition but goes far beyond them in creating a sense of musical inevitability even while pursuing the most remote harmonic connections. A young composer in search of a valid musical technique, Purcell’s polyphonic method depends on a new harmonic sensibility wholly his own.

No amount of historical study prepares one for the originality and daring of viol consorts by William Lawes. One senses a restlessness in the compositional impulse and a straining for novelty at all costs, attitudes that might easily have produced musical nonsense. To solve the puzzle of Lawes, one could focus on his influences and his social context, but they in no way account for his wayward musical personality. Attuned to his topsy-turvy world, one begins to hear in every piece an undiscovered place that had not been mapped before. The clarity of utterance is remarkable, for in overturning venerable rules of dissonance treatment, and deforming classical ideas found in the works of others, Lawes can persuade you that backward is forward, that chaos is ordered, that ugly is beautiful. Lawes—along with some of his forbears and contemporaries—counts as an English eccentric, but one whose musical insights remain remarkably trenchant and contemporary. Yet not all of Lawes’s consorts are all darkness and doom. The pure pastoral sunshine found in the F-major Paven is matchless, but like so many great composers Lawes cannot refrain from the admixture of piquant dissonances that cast memorably doleful shadows. He also knows how to revel in playfulness, in which the pleasures of making music with a group of congenial friends are treated as compositional topics of invention. And for all his attraction to the arcane, Lawes—unexpectedly—has also something delightful to say about innocence with music that rejoices in its diatonic naivete.

Laurence Dreyfus is the founder and artistic director of Phantasm. In addition to his work as a performer, he has also pursued a career in musicology and has taught at the universities of Yale, Stanford, Chicago, Oxford, and King's College London, among others. His publications to date include books on J.S. Bach and Richard Wagner.

The Ensemble

Phantasm

Phantasm was founded in 1994 by Laurence Dreyfus and is widely regarded as today’s leading viol consort. The five musicians first won international acclaim when their debut album featuring music by Henry Purcell was honored with a Gramophone Award as Best Baroque Instrumental Recording in 1997. Further Gramophone Awards followed for recordings of Orlando Gibbons’s viol concertos and John Dowland’s Lachrimae. Phantasm has appeared at major concert halls and Early Music festivals, among them trigonale in Austria, Dresden’s Heinrich Schütz Music Festival, the Barcelona Early Music Festival, the Bergen International Festival, the Stockholm Early Music Festival, and London’s Wigmore Hall. Phantasm’s repertoire is focused on English music of the Renaissance and Baroque eras, but the quintet also performs French and Italian music and the works of Johann Sebastian Bach. Since 2015, Phantasm has been based in Berlin, after serving as consort in residence at the University of Oxford’s Magdalen College for a decade. The group most recently appeared at the Pierre Boulez Saal in 2023 as part of the interdisciplinary performance The Art of Being Human.

October 2024